One of the big barriers to learning a new tool new is the uncertainty about whether it will provide more value than the tools you’re already using and thereby justify the time and effort needed to master it. To address this concern, in the final chapter of this (and each subsequent) part, we’ll take a high-level look at some popular business tools and compare them with Wardley Maps. We’ll begin by examining two of the most widely-used frameworks for strategy development: the SWOT analysis and the Business Model Canvas (BMC).

SWOT ANALYSIS

When talk turns to strategy in most organisations the thoughts of many leaders turn to a SWOT analysis — comparing your Strengths, Weaknesses to rivals and exploring market Opportunities and Threats. The aim is to match an internal strength with an external opportunity to create a ‘strategic fit’ between what the market needs and what you can do better than rivals. This then forms the basis of your competitive differentiation.

The origins of the SWOT analysis are unclear, but it’s been around since the 1950s or 60s, making it older than almost any of the executives (and many of the organisations) still using it today. This either speaks to its enduring power, or the lack of evolution in business strategy over the last 60 years. Let’s take a dive into the SWOT analysis process first, before remarking on some positives and negatives of this tool.

Process

To perform a SWOT analysis, gather a small group of people with knowledge of your organisation and the market you’re focusing on. Then:

- Define the scope and objective of your analysis (e.g. enter new market X, launch new product Y)

- Collect relevant data (e.g. market research, customer surveys)

- Identify key competitors in this space

- Evaluate your organisation’s strengths and weaknesses relative to these competitors

- Explore market opportunities and assess potential threats in the target space.

Fig.92: Typical SWOT Analysis Output

Finally, create a SMART plan (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) that leverages your strengths to seize opportunities, whilst addressing weaknesses to mitigate potential threats.

Positives

The positives of performing a SWOT analysis are that it’s relatively straightforward and inexpensive to run, which likely explains its enduring appeal to executives. As a collaboration-based tool, it also encourages everyone attending to contribute, which helps taps into the collective intelligence of the group. And, if relevant data for points 2 and 3 in the process above can be gathered in advance, the entire SWOT analysis can be completed in an afternoon, making it a quick and efficient way to ‘do strategy’.

Negatives

However, a SWOT analysis has some key deficiencies:

- No Competitor Comparison — When done properly, a SWOT analysis compares your Strengths and Weaknesses against competitors. However, due to the difficulty of gathering reliable data on rivals, many organisations neglect this step (as in fig.92). But perceived Strengths could, in fact, be relative Weaknesses compared to competitors, which could spell disaster if you attempt to compete there.

- No User Needs — There’s also no mention of user needs in the example above. While we might be tempted to enter the “new niche markets” mentioned under Opportunities, if we don’t know what users in those markets need, or whether we’re capable of satisfying those better than rivals, then entering these markets based on this information alone would be a risky leap into the unknown.

- Oversimplification — SWOT analyses reduce complex business situations into a few bullet points, which is a big part of their appeal. However, this leads to superficial thinking. Determining strategic moves from the analysis above would require significant further thinking, but with only a summary of the situation here, there’s limited opportunity to challenge assumptions and discover what to do next1.

- Unclear Priorities — Unless we assume the order of bullet points has significance, the SWOT analysis above provides no guidance as to which Opportunities we should prioritise. But without a clear focus on what matters, we’ll fail to find fresh insights — sudden and unexpected shifts to better stories that lead to breakthrough action2. And if we aren’t uncovering new paths to victory, is this even strategy?

- Static Snapshot — Finally, the SWOT analysis above only provides a snapshot in time, with no indication as to how this landscape might be evolving. Creating a SMART plan based on this would lock us into a course of action for the future, based on a superficial understanding about it from the past. We’d risk acting in the world that no longer exists, rather than adapting to how it’s changing.

Conclusion

A SWOT analysis is quick and easy to do, but it only offers a superficial view of the Landscape you’re operating in and doesn’t lend itself to the rigorous challenge needed to discover better strategic moves. When used at the right time a SWOT analysis can be useful (e.g. comparing offerings against those of rivals). But this comes after answering more fundamental questions further up the ‘hierarchy of strategic thinking3’:

- HOW you’re going to do something (operational decisions)? Which requires first deciding

- WHY you’re making this move over that one (strategic decisions)? Which requires first understanding

- WHERE your options for action are (awareness)? Which requires seeing the Landscape clearly first — and this is why we use a map.

Organisations that rely on SWOT analyses for strategic thinking often take action based on their ‘Strengths’ alone — but this is a trap. They do things simply because they’re good at them, rather than because there is sufficient demand from paying users. Furthermore, the greater they perceive this strength to be, the longer they continue doing it — sometimes long after it has ceased providing any real benefits to anyone4. Organisations can also be seduced by the seemingly lucrative ‘Opportunities in a SWOT’, overlooking the fact that competitors can pursue these too. Failing to consider competitors’ relative advantages can result in leaders marching their organisations into battles they can’t win, only realising their ‘Weaknesses’ when it’s too late. This happens because the SWOT analysis they relied on was superficial, and their decisions were driven more by hope, wishful thinking, or the opinions of the highest-paid person in the room. As a result, their analysis missed the biggest “Threat” of all: a SWOT is “a dreadful way to start a strategy process5”.

BUSINESS MODEL CANVAS (BMC)

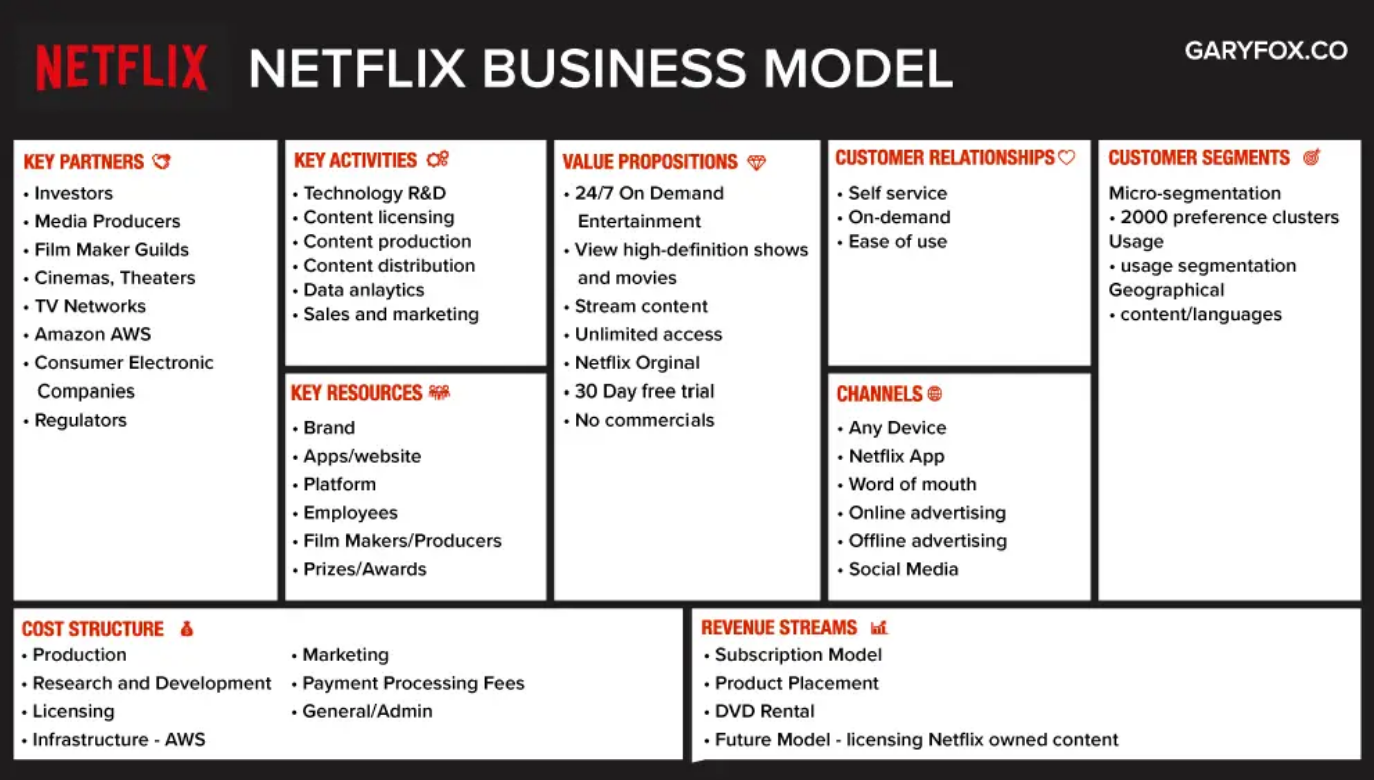

Another popular (and more recent) tool widely used for strategy is the Business Model Canvas (BMC). It outlines nine key categories that should be considered when making a strategic move (e.g. launching a new product or entering a new market). These categories cover everything from the ‘key partners’ required to create a ‘value proposition’, to the ‘key resources’ needed and potential ‘revenue streams’ expected. The BMC therefore provides a clear, thorough overview of how to create value from a strategic move.

Fig.93: Example Business Model Canvas For Netflix

Positives

The BMC balances simplicity with thoroughness. Its nine categories force an organisation to consider all the resources and information required, while presenting this on one page, making it clear for everyone to see. The nine categories cut across traditional functional lines — ‘value propositions’, ‘customer relationships’, ‘channels’ and ‘customer segments’ span traditional marketing and sales; whilst ‘key resources’, ‘cost structure’ and ‘revenue streams’ cut across operations and finance — to create a holistic view of how the organisation creates value by working together. This encourages cross-functional collaboration and learning.

Negatives

The BMC has a category called ‘customer segments’ but provides no insight into what these users either want or need, which is the same limitation identified in the SWOT analysis above. The BMC focuses more on what the organisation needs to do to push its products onto the market, (as outlined in its ‘value propositions’), but without a voice of the user, the assumption that users want or need what’s being offered goes unchallenged.

As with a SWOT analysis, it isn’t clear from looking at a BMC what the most important things are to focus on. There’s no indication whether the order of components within a category has any significance. For instance, is ‘self-service’ more important than ‘ease of use’ in the ‘customer relationships’ category on the Netflix BMC above (fig.93)? That’s lack of clarity arises because the BMC provides no insight into what users value most.

The BMC shows that people from different functions must work together to create value, but provides no guidance as to how they should do this. The usual defence to this criticism is that, ‘the BMC is a tool for strategy development and not execution’, but this risks falling into the trap discussed earlier6 — dividing strategy into ‘thinkers and doers’, with the former creating unrealistic plans the latter can’t implement.

Using the BMC as an executive summary of a strategic thinking process is good way to use it, but it’s limited as a tool for creating strategy because it doesn’t facilitate the deeper discussions needed to discover new insights. We’re simply left with a binary choice: either accept these findings as they are or reject them, as we have no way of challenging or developing them. For that, we need something else — such as a map.

Conclusion

Aficionados of the SWOT analysis and BMC will (rightly) point out that these tools are summaries of a deeper thinking process, much like a map summarises the deeper work of a cartographer. However, unlike a map, which provides a neutral view of a Landscape that others can use to challenge assumptions and discover better paths forward (e.g. “we should go this way, rather than that, as it seems shorter”), the SWOT and the BMC are difficult to challenge once completed. This is because they offer no insight into user needs or priorities. We only see the conclusions, forcing us to either accept them fully or reject them outright. Yet rejecting the results of a SWOT or BMC often means starting the entire process again — something that, due to time and money already invested in a process that didn’t deliver the desired results the first time round, leaders are understandably reluctant to do.

This is where a map proves superior, because once created, it can be used by different people to explore various moves, using the map to challenge assumptions and support their arguments (e.g. “yes, that way may be shorter, but it’s far more challenging and risky than taking this path here”).

***

So far, we’ve only shown how to create a Wardley Map and use it to understand an industry better (see previous chapter7). Turning these maps into tools for better strategic thinking requires some further steps.

In the same way a physical Landscape is changed by Climate patterns — think of a river in summer that can only be crossed by boat, but freezes with the onset of winter, making it possible to cross on foot — our business Landscapes are also shaped by Climate patterns. We call these the ‘economic rules of the game’. And, like the unavoidable changes to physical Landscapes wrought by Climate patterns, these economic forces are changing your business Landscape, whether you want them to or not. However, with an understanding of these patterns, applied intelligently to a map of your Landscape, you can begin to anticipate how the future of your industry will evolve — providing an early warning system of emerging opportunities and threats that you can now respond to quicker and smarter than your rivals: giving you a competitive edge.

We explore these Climate patterns, or economic rules of the game, in the next part of this book.

1 For the importance of learning from challenge see chapter sixteen — The Importance of Challenge

4 We explore this in more depth in part four.

7 Chapter nineteen — Mapping an Industry