“Why would an organisation not want to see the landscape they’re competing in?” — Simon Wardley

In any competitive environment — a game, warfare, or business — players have a clear Purpose: to win. If asked how they intend to win a chess player or a general can point to a visual representation of their situation, a chessboard or a map, and explain why they’re making these moves here instead of those moves there. But, in business, most leaders lack any reliable visualisation of their Landscape and therefore struggle to explain their course of action, beyond echoing popular buzzwords or making vague references to “best practices1”.

In business, strategy often comes in a PowerPoint presentation, filled with 2x2 matrices, and backed up by detailed spreadsheets promising positive returns on investment far into the future. The ‘strategic plan’ is signed off by the board and rolled out to “doers” to execute. But, in competitive environments where others have a say in how things unfold, ‘no plan survives first contact with reality2’ because you’re not in control of all the variables — such as, customer behaviour, competitors’ responses, or even how your team executes. Winning therefore requires more than a rigid plan — it requires real competitive advantage and the best tool for exploring an uncertain terrain and finding what you’re looking for is a map.

The Power of Maps

Imagine you’re in a foreign city where you don’t speak the language. You have a meeting that day so ask your multi-lingual hotel receptionist how to get there. The receptionist writes out a detailed set of instructions and you set off, following the instructions to the letter. But half way there, the street you must turn on to is closed. What do you do? You can’t ask anyone as you don’t speak the language. You could try and take a detour, but risk becoming hopelessly lost if you get it wrong. You could also retrace your steps and go back to the hotel for alternative instructions, but this means you’re going to be late.

Fortunately, hotel receptionists usually give you a map, circling where you are now and where you’re aiming to get to. Now, you can clearly see your options for movement and track progress as you go. If there are any obstacles on the way you have a tool to orientate yourself and find a new way. This is the power of a map for navigating unknown Landscapes. And now it’s possible to create real maps for business Landscapes too.

Think WHERE before WHY

Before we dive deeper into mapping let’s consider the following hierarchy of strategic thinking:

- Before you decide WHO does WHAT by WHEN (tactical decisions)

- You need to decide HOW you’re going to do this (operational decisions)

- And before deciding HOW you’re going to do this, you need to decide WHY you’re doing this over that (strategic decisions)

‘Strategic decisions’ — why enter market A over B, why build product X over Y — are challenging because they’re about the future, which is an uncertain place. Therefore, before trying to answer the ‘WHY of strategy’ (why do this over that) focus on discovering WHERE your options are first. Identifying multiple WHERES you can make moves helps prevent you from getting stuck on the first idea that makes sense. It also helps you to communicate strategic choices better to others, as now you can explain why you’re doing A rather than B. This helps aligns people around your strategic choices — a critical first step in executing strategies effectively.

Thus, the ‘hierarchy of strategic thinking’ is to think:

- WHERE before WHY

- WHY before HOW

- HOW before WHO, WHAT & WHEN.

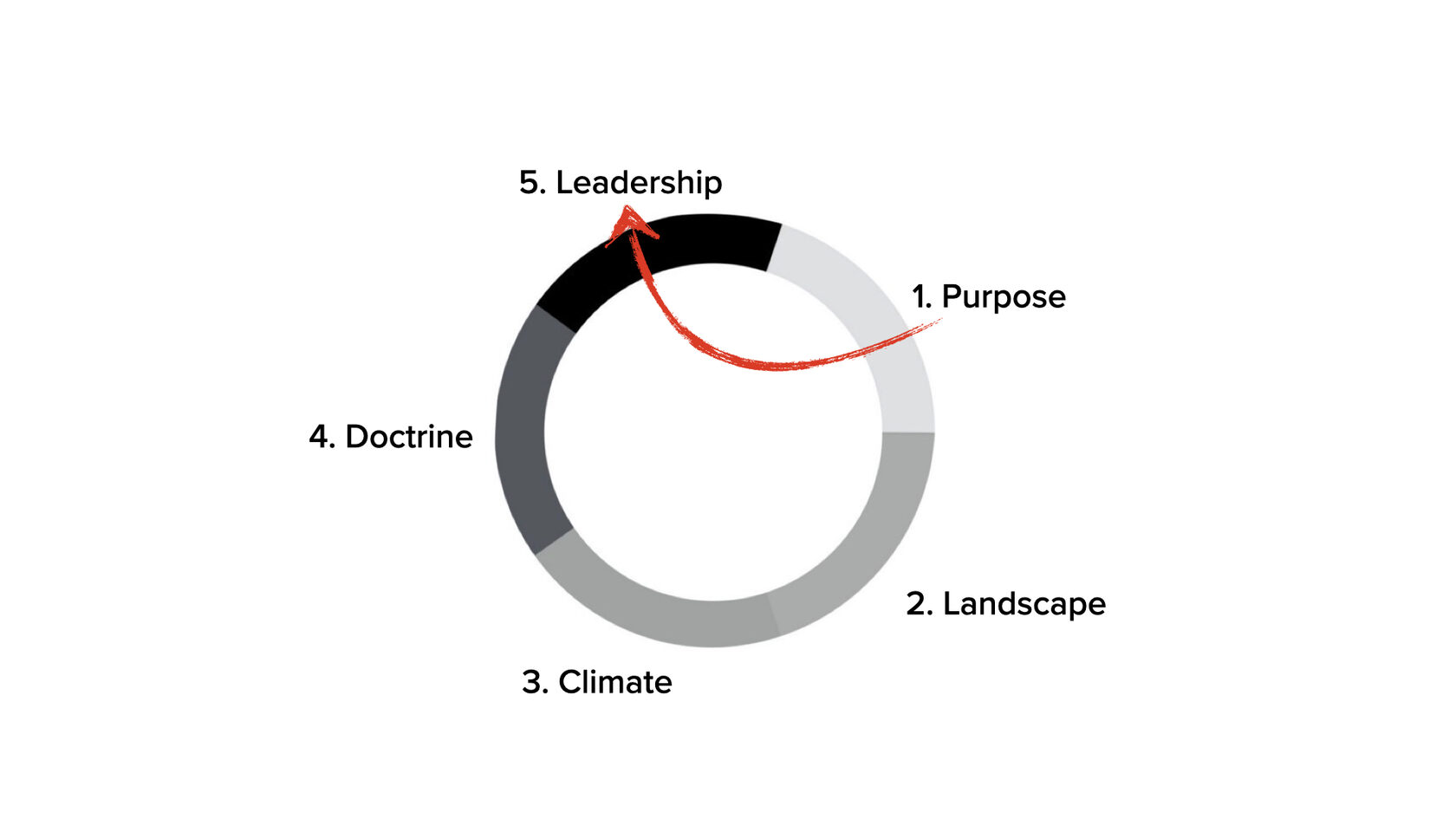

Unfortunately, many leaders jump directly from Purpose (“to win!”) to Leadership decisions about WHO must do WHAT by WHEN without ever seeing the Landscape clearly, understand how it’s changing or identify where the real threats and opportunities are. The result is a ’tyranny of tactics’ — action poorly commanded and controlled by KPIs and OKRs, with little thought as to HOW all the different parts should be coordinated (beyond copying what everyone else is doing) and failing to answer the most fundamental question teams have — “WHY are we doing this?” — leading to confusion and the appearance of an ‘execution gap3’.

Fig.25: Jumping From Purpose to Leadership Decisions

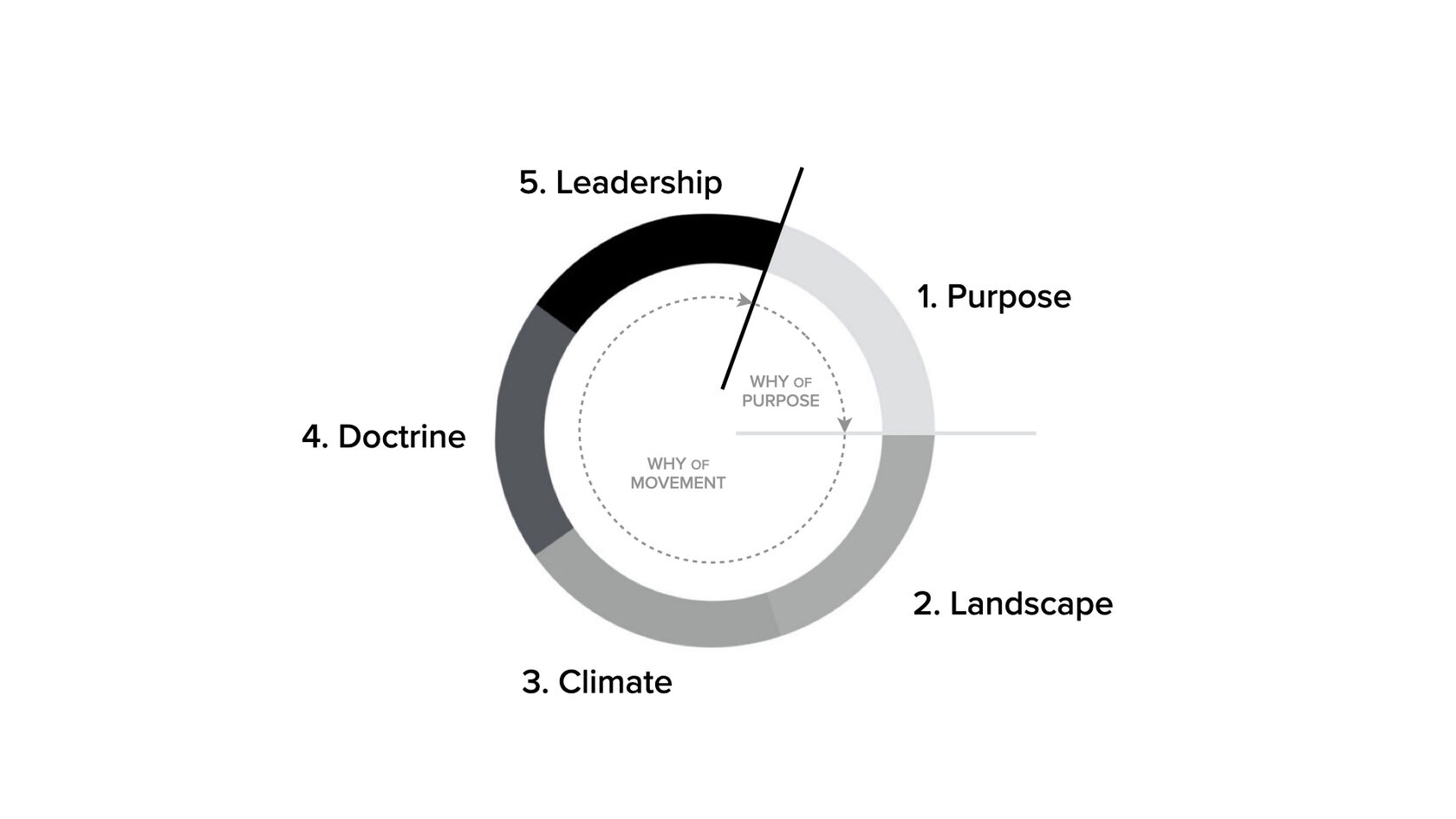

Two Types of WHY

The most important question in strategy is WHY. However, there are two types of why and most organisations only answer one: the ‘WHY of Purpose’ — why are we doing this? Typically, this becomes the organisation’s vision or mission (“We aim to be the leading provider of A in market B …”) and smart organisations will also provide a good reason for doing this (“… we believe in X or we’re trying to make Y happen”).

For example, Tesla’s WHY of Purpose is to: “Accelerate the world's transition to sustainable transport4”. A compelling Purpose that can inspire people by showing them a glimpse of a future the organisation is working to make happen. This vision can then cascade throughout the organisation to align people around it:

- Higher Purpose — Accelerate the world's transition to sustainable transport.

- Project Purpose — Build an electric sports car that competes with gasoline alternatives.

- Team Purpose — Make ‘big leaps’ in key technologies A, B, C to advance electric vehicles.

However, answering the WHY of Purpose alone isn’t enough, because there’s a second type of WHY that is just as crucial: the ‘WHY of Movement’ or “WHY are we doing this and not that”. Tesla, to accomplish its higher Purpose, must continually respond to emerging opportunities and threats (e.g. new technological breakthroughs, unexpected competitor moves, regulatory changes, and the fluctuating costs of financing). Choices must be made: WHY should they focus on this and not that one? WHY should they invest in this technology and not that? WHY should they build this in-house but outsource that?

Fig.26: Combining the “Strategy Cycle” with the “Two Types of Why”

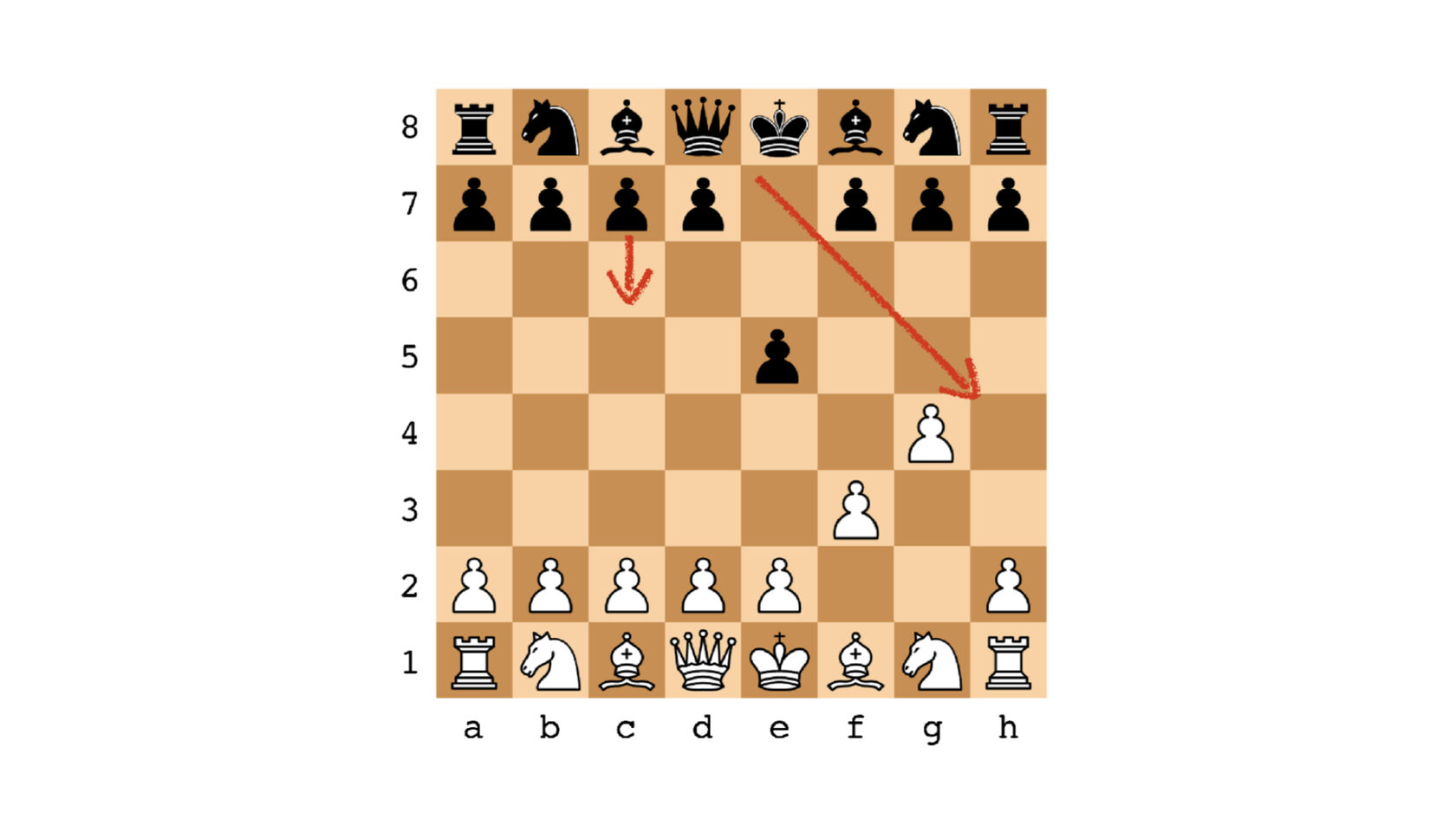

Answering questions about the ‘WHY of Movement’ — why make these moves instead of those — is how we learn to exploit conditions to our advantage. But to do this we need to be able to see the Landscape first. In chess or weiqi, players can see the board (their Landscape), which enables them to compare possible moves and answer WHY, for instance, Queen to h4 is a better move than pawn to c6.

Fig.27: The Why of Movement in Chess

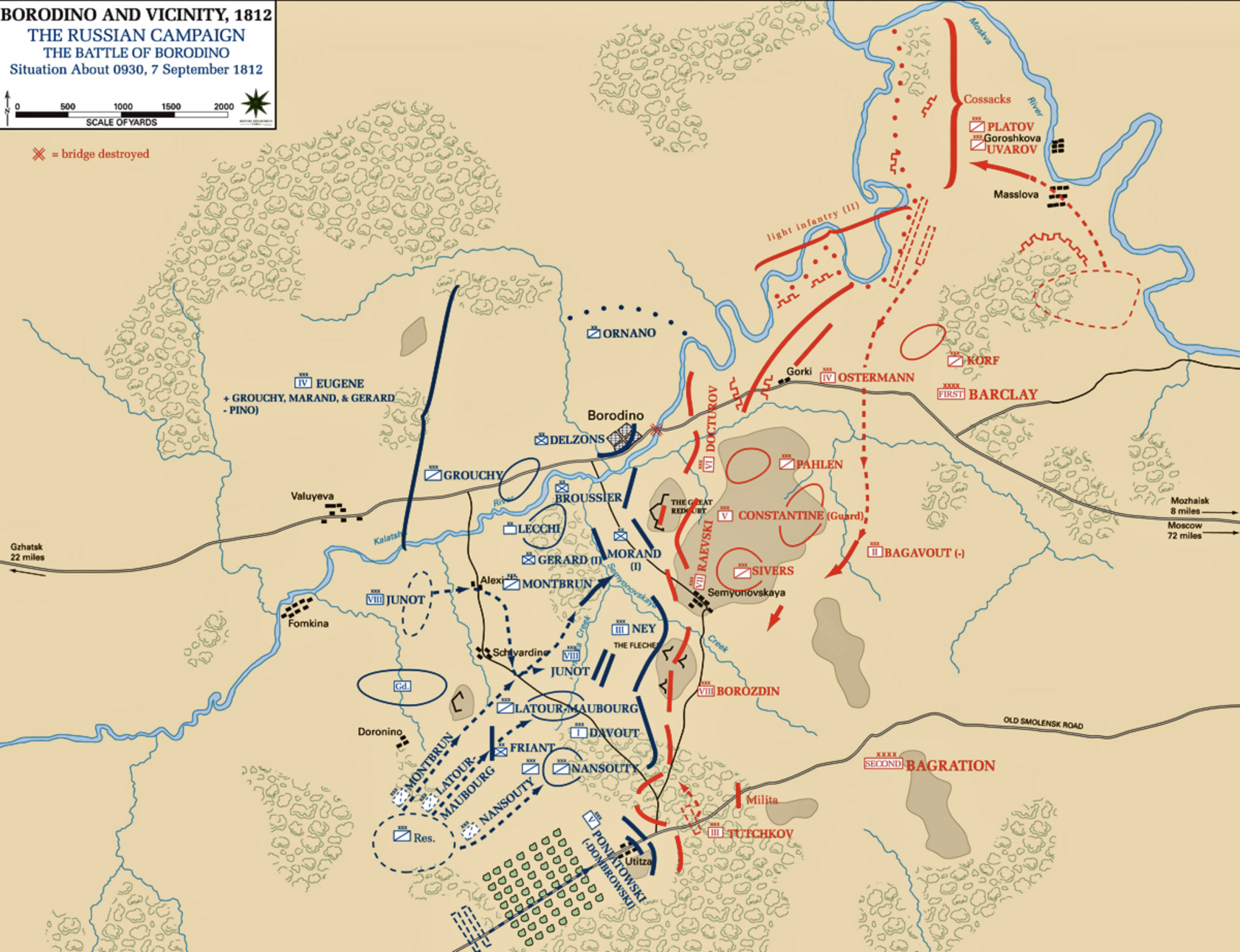

In warfare, generals use maps to see the physical Landscape where battles take place. This enables them to identify where threats are coming from (e.g. enemy troops amassing in the North) and where the opportunities are they can exploit (take the high ground here and provide covering fire for the left flank).

Fig.28: The Why of Movement in Warfare (Borodino — 1812)

Yet, the business world has no way to visualise its Landscape clearly, which renders most of its leaders blind, making critical decisions based on narratives, numbers with minimal context or gut instinct. Faced with the growing uncertainty of today’s more volatile world and armed with an imperfect arsenal of tools better suited to a previous, more predictable age, is it any wonder that so many leaders turn to those peddling the certainties of silver bullets based on “best practices”5, case studies6 or “doing what Elon would do7”.

We must demand more from strategic thinking in business. Fortunately, there is a better way.

1 For an exploration of the dangers of following “best practices” see the Introduction: Why "Best Practices" Are Holding You Back.

2 “No plan of operations reaches with any certainty beyond the first encounter with the enemy's main force”.

Helmuth von Moltke. Kriegsgechichtliche Einzelschriften (1880)