As did many others, I started writing a book when COVID-19 struck. When our certainties are challenged — such as, people must go to an office to work and that global supply chains are always good for economies — we tend to seek out new certainties to replace the old ones with. And where there is demand, supply rises up to meet it. I knew then, that by the time I finished the long process of writing my own, thousands of other books by thousands of gurus (both old and new) would already have been published revealing, “The Secrets of Success in Our New, New Normal World”. I knew this would happen because a wise man once told me, “the reason there are so many gurus in the world, is that so few people know how to spell charlatan1.”

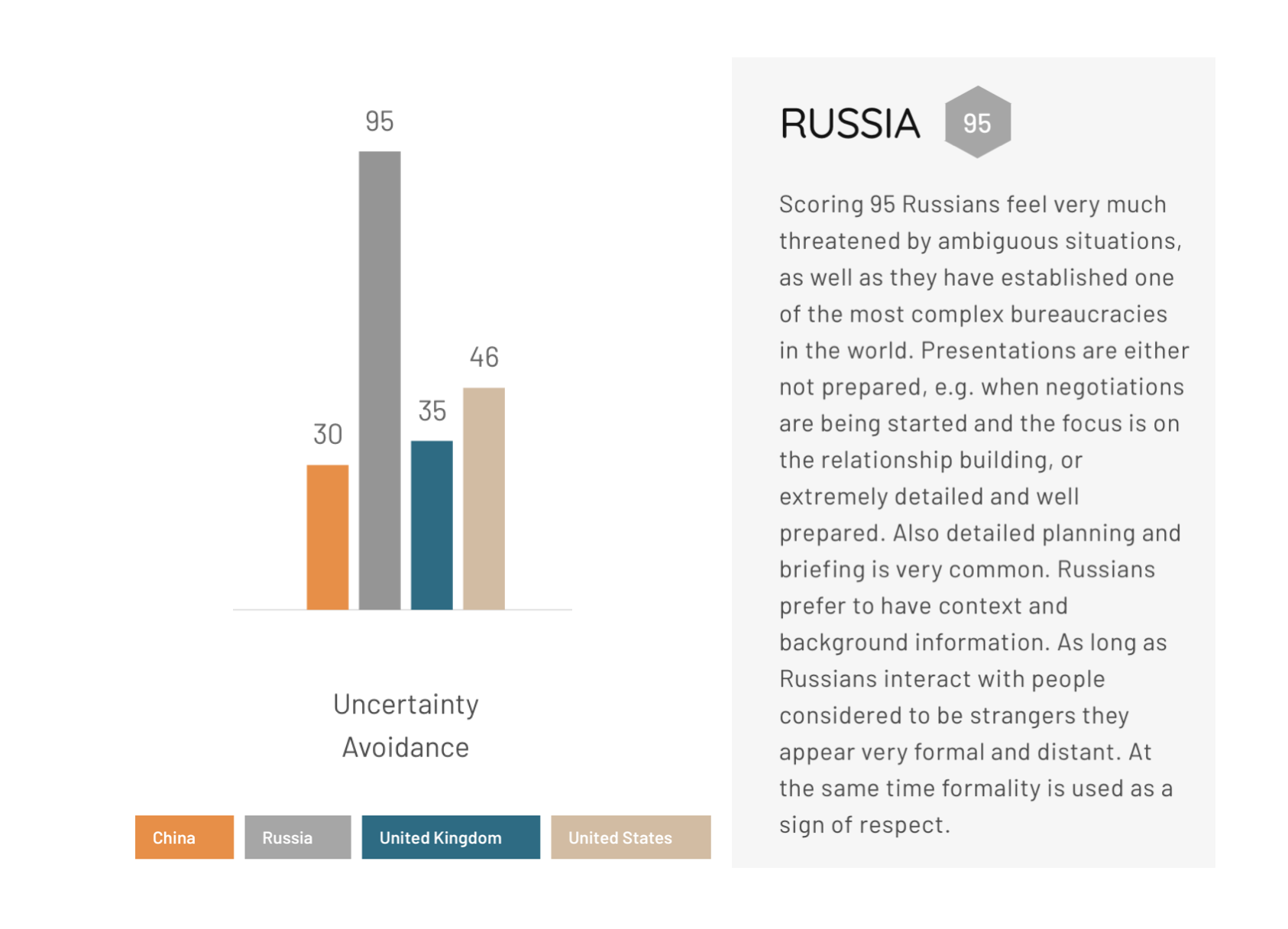

I’m British, but I’ve lived in Moscow for a long time, providing me an intimate relationship with uncertainty. Modern Russia was born from the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and plunged into chaos following the disastrous ‘economic shock therapy’ that started in 1992, culminating in a sovereign debt default and banking crisis in 1998. The deep recession that followed the 2008 global financial crisis brought with it more uncertainty, which has since been exacerbated by growing geopolitical tensions from 2014, peaking in 2022. Unsurprisingly perhaps, Russia has developed an acute sensitivity to uncertainty (see fig.1).

Fig.1: Russian Uncertainty Avoidance Against Select Other Countries (Hofstede2 Cultural Dimensions)

Cultures with a high uncertainty avoidance tend to crave detailed plans and predictions about the future that provide a comforting belief that someone, somewhere is in control. Yet, in a volatile world, certainty is an illusion beyond the gift of any individual, group, or nation to provide. This may explain why, as we enter a new “Roaring Twenties” (or “Screaming Twenties”) so many businesses are struggling to adapt. Many are constantly blindsided by changes their predictions failed to foresee and their plans failed to prepare them for. To survive in response to these disruptions they cut costs. But to thrive? Many do little more than hope for a swift return to normality but, as we should all have learned by now, hope is not a very good strategy.

In my conversations with business people around the world, it started to become clear to me that many feel the old ways of working are simply not working anymore and are looking for something different. That’s why I started to write this book — to introduce an alternative way of thinking and acting; one that is both new but also rooted in timeless principles that are appropriate for the complex world we find ourselves in today. Starting in the next chapter I’ll attempt to provide insights into this new thinking that are relevant for all. But, for now, I’ll begin where I was in those chaotic early days of 2020 — focusing on Russian businesses.

The Case of Russia

Private business in Russia only became legal in 1988, meaning its market economy is still young and experiencing growing pains. In its wild first decade, a new class of entrepreneurs took the risks required to unlock oversized rewards. In its second decade, the market stabilised and the rewards accrued to those who did things better, not just first. During that period a different type of business leader emerged, primarily graduates of the country’s strong STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) education system. Trained to seek ‘right answers’ they turned their gaze westwards to where the leading businesses were. Anyone doing business in Russia at this time will recall the obsession with copying ‘western best practices’ that became the standard operating practice of most, if not all, Russian businesses.

Learning from others is wise, but blindly imitating the ‘best practices’ of others meant that many Russian businesses failed to create a unique competitive advantage for themselves. Few believed they could compete with western firms, so accepted being ‘second rate’, as long as they were better than their local Russian rivals. They competed by finding the latest thing from the West and the most expensive ‘guru’ they could find to guide its implementation. Despite having one of the largest, best-educated populations in the world3 many Russians were simply not thinking for themselves — an absurdity captured in a joke by the business consultant, Ichak Adizes:

A man, seeking a brain transplant, visits a renowned brain surgeon.

The surgeon tells him he can have the brain of an Ivy League professor for $5,000.

The man thinks for a moment and asks, "What else do you have?"

"The brain of a Nobel Prize-winning physicist. This one costs $10,000" replied the surgeon.

The man thinks for a moment before asking, "What's the most expensive brain you have?"

The surgeon pauses briefly. Then picks up a brain. "I have this one. Mikhail, ordinary Russian man. But this costs $50,000."

Puzzled, the man, asks, "Why is it so expensive?"

"Ah!" replies the surgeon, "never been used!"

To their credit, Russians usually laugh when I retell this joke, but there's a serious warning here — what worked yesterday, somewhere else, for someone else will not work for you today, for as the Greek philosopher Heraclitus asserted, “no man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man." We can’t rely on following the paths others have taken because of three inescapable problems:

- Form over substance

- Sensitivity to initial conditions

- Playing not to lose (when others are playing to win).

1. Form Over Substance

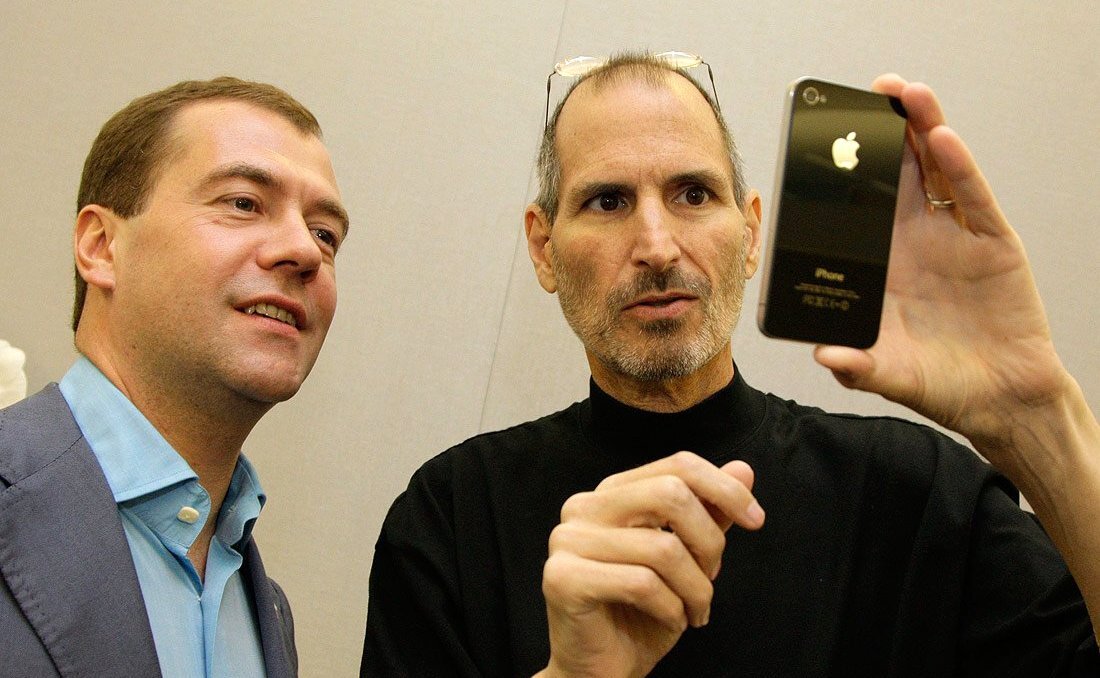

The global financial crash of 2008, triggered by sub-prime mortgage loan defaults on the US West coast, hit Russia’s economy harder than most due to its lopsided dependence on natural resource exports. In response, then-President Dmitry Medvedev declared that Russia would modernise4 and become an innovation-led economy. He looked westwards for answers and his gaze fell upon Silicon Valley — the most innovative hub of the most innovative nation. Soon, massive investment was pouring into the ‘Skolkovo’ project in Moscow — Russia’s attempt to build its very own Silicon Valley. However, more than a decade later results remain underwhelming5.

Fig.2: Then-Russian President Dmitry Medvedev and Steve Jobs (2010)

Copying form (what something looks like today) without understanding the substance (the underlying principles it was built on and the many individual actions taken over time) is a common trap that many who seek simple answers to complex questions fall into. Physicist Richard Feynman described this as cargo cultism, which he memorably illustrated with the story of South South islands where, firstly Japan, then later the US had based part of their Pacific Ocean supply chains during World War II:

During the war they [the islanders] saw airplanes land with lots of materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas — he’s the controller — and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So I call these things Cargo Cult Science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.

As the underwhelming results of the Skolkovo project demonstrate, cargo cultism — copying superficial form without understanding the deeper substance — is not limited to the South Pacific.Success can't be re-created by following someone else's path. Success requires finding what works for you, in your conditions, today.

2. Sensitivity to Initial Conditions

However, even if we understand the substance of a system, copying it doesn’t guarantee success, due to a principle called sensitivity to initial conditions. This principle comes from the meteorologist Edward Lorenz who, in 1960, was running multiple weather simulations that, to his amazement, produced dramatically different results despite using identical inputs. Eventually he found the cause — a single data input had been rounded down from 0.506127 to 0.506 — a tiny error, but enough to cause a massive variation in results.

Lorenz’s discovery startled those who believed that, with enough data, the future of any system could be predicted. He had discovered that complex systems, like weather patterns, are highly-sensitive to initial conditions where even the smallest difference in starting conditions can lead to huge differences in outcomes. This is because of feedback loops, where the outputs the system produces are continually fed back into the system as inputs, (e.g. rising temperatures cause Earth’s polar ice to melt, which means more sunlight is absorbed, further increasing temperatures) creating a cyclical relationship that dramatically amplifies even the tiniest differences, causing the entire system to evolve in completely unpredictable ways.

Lorenz’s insight didn’t just apply to weather patterns but to any complex system — organisations, or ecosystems like Silicon Valley. Complex systems contain countless parts that interact with each other in non-linear ways as small changes catalyse disproportionately large effects (e.g. a tiny virus that shuts down entire economies, or a new technology that re-shapes how multiple industries operate). Therefore, when we try to copy a complex system, any of the countless tiny differences in our starting conditions (e.g. people, ideas, technologies, time) will, like the rounding error in Lorenz’s weather simulations, cause wildly different outcomes. Hence why copying ‘best practices’ never produces the same results twice in complex systems.

3. Playing Not to Lose (when others are Playing to Win)

Even if you could overcome the insurmountable problems of form over substance and sensitivity to initial conditions there’s another reason copying ‘best practices’ is not a best practice: the entire time you’re trying to imitate what market leaders did yesterday, they’re busy pulling even further ahead of you tomorrow. Allowing market leaders to stay ahead in exchange for taking on the uncertainty of charting new paths is a compromise many businesses that are ‘playing not to lose’ find acceptable. However, this is only viable strategy if all your peers are doing the same thing. But, competitive markets are open markets, meaning new rivals enter the game and if they’re ‘playing to win’ you will soon be in a battle for survival.

As Europe’s largest economy Russia attracts globally competitive businesses that are eager to capture talent, customers and profits. Today, these are new industry giants like Huawei, Haier and BYD who are out-competing the same western firms in global markets that Russian businesses failed to challenge in their own. To protect their market share, Russian businesses need to raise their game, to stop copying outdated ‘past practices’ and embrace uncertainty, using their vast thinking potential to chart new paths forward:

If your competitor’s boat gets ahead of you at the starting line, the instinct is to chase it. To tack where it tacks. But if you do, you will always be behind, because you will be sailing on the same path, subject to the same wind. And in fact, for much of the time, you will be sailing in their ‘dirty air’ — they get the full wind in their sails, which breaks up the effect of the wind on your sails. Your only hope is for the leader to make a terrible blunder. Otherwise, you will race for hours and hours, tacking dutifully behind the leader and cross the finish line behind them. If you want to end up in some place other than last, you need to tack away and plot a different course that will get you to the finish line ahead6.

The arrival of next-level Chinese firms is both a threat, but also an opportunity for Russian businesses. Competition will force them to sharpen their skills and raise their game, which may mean, in future, they will finally be able to compete against western firms on global markets. But, for those who don't adapt, they can look forward to a future where they get swallowed up by Chinese and local Russian firms 'playing to win'.

What Is To Be Done?

In the 1990s, Chinese businesses faced many of the same challenges Russian businesses did: an impoverished economy, historical suspicion of private enterprise and inferior technology compared to western competitors. Yet many Chinese businesses transformed themselves into global powerhouses in an incredibly short time. How did they do this?

The first think to note is what they didn’t do. Although they actively learned from the West (often with sharp practices Westerners complained about7) they didn’t blindly copy ‘western best practices’. They didn’t have to. As this book will demonstrate, the East has a rich tradition of strategic thinking that helps one navigate uncertainty effectively. It is this strategic thinking that guided the rapid development of Japanese businesses in the chaotic aftermath of World War II last century and the meteoric rise of Chinese businesses this century.

However, the argument made in this book is not that Russian businesses should start copying ‘eastern best practices’ (for the reasons outlined: form over substance, sensitivity to initial conditions and the sub-optimal strategy of playing not to lose) but should instead learn from the East in ways that Westerners cannot (or choose not to). Eastern strategic thinking is very different and some have argued that Westerners struggle to grasp the Eastern approach to strategic thinking8. This presents Russian businesses with their opportunity.

Russia is different. Its national symbol — the double-headed eagle — reminds us that Russia has always looked both eastwards as well as westwards. This duality positions Russians to absorb the essential lessons from the Eastern approach to strategy that appear to elude Westerners and use these insights to outcompete their rivals in the competitive game of business. But this must start with Russians ceasing the imitation game and instead harnessing their immense intellectual potential to chart their own paths forward.

The first step is to STOP making strategic plans.

1 Roger Holdsworth

4 Modernisation is a theme in Russian, Soviet and post-Soviet history, reoccurring every 30-60 years. From Peter the Great, who founded his new capital — St. Petersburg — in 1703 in an attempt to modernise Russia and catch up with other European nations. Followed by Catherine the Great’s modernisation of the political and legal codes to improve state efficiency, economic growth and maintain stability as the empire grew. To Alexander I who modernised the military in response to the new age of war ushered in by Napoleon. Then the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, Stolypin’s reforms starting in 1906, Stalin’s Industrialisation of the 1930s and Gorbachev’s Perestroika of 1985.

5 In 2008 the Global Innovation Index ranked Russia 68th in its list of global innovators. By 2021 it ranked Russia 45th, behind other ‘upper middle-income economies’ like Bulgaria, Malaysia, Turkey and Thailand. While such reports should be used critically (as, for example, methodologies change) these results suggest Russia’s innovativeness is little changed, despite the huge investments into Skolkovo.

7 Though much complained about the practice of appropriating ideas from other countries is nothing new https://www.history.com/news/industrial-revolution-spies-europe

8 This appears to be the central hypothesis of Derek Yuen in his book ‘Deciphering Sun Tzu’ which will be explored further in chapter eight.