In late 2020 I met with an executive from a leading retailer. While waiting, I had the chance to review the company’s strategy which, unusually, was pinned to the wall of their conference room. Here was a meticulously crafted plan detailing the company’s vision, mission, values and key performance indicators (KPIs), with a GANTT chart showing project deadlines. It had clearly taken a lot of time and — judging by the embossed logo of the high-profile strategy consulting firm on the paper — a lot of money to create.

The executive arrived and sat down. I gestured to the strategy on the wall behind him. He didn’t turn round:

Me: I was looking at your strategy. Quite the undertaking.

Executive: [disinterested] Mm

Me: How is it holding up under COVID?

Executive: It isn’t.

Me: Will you be hiring [the strategy firm] again for next year?

Executive: No. I think we need something different.

Executive: [disinterested] Mm

Me: How is it holding up under COVID?

Executive: It isn’t.

Me: Will you be hiring [the strategy firm] again for next year?

Executive: No. I think we need something different.

I couldn’t agree more.

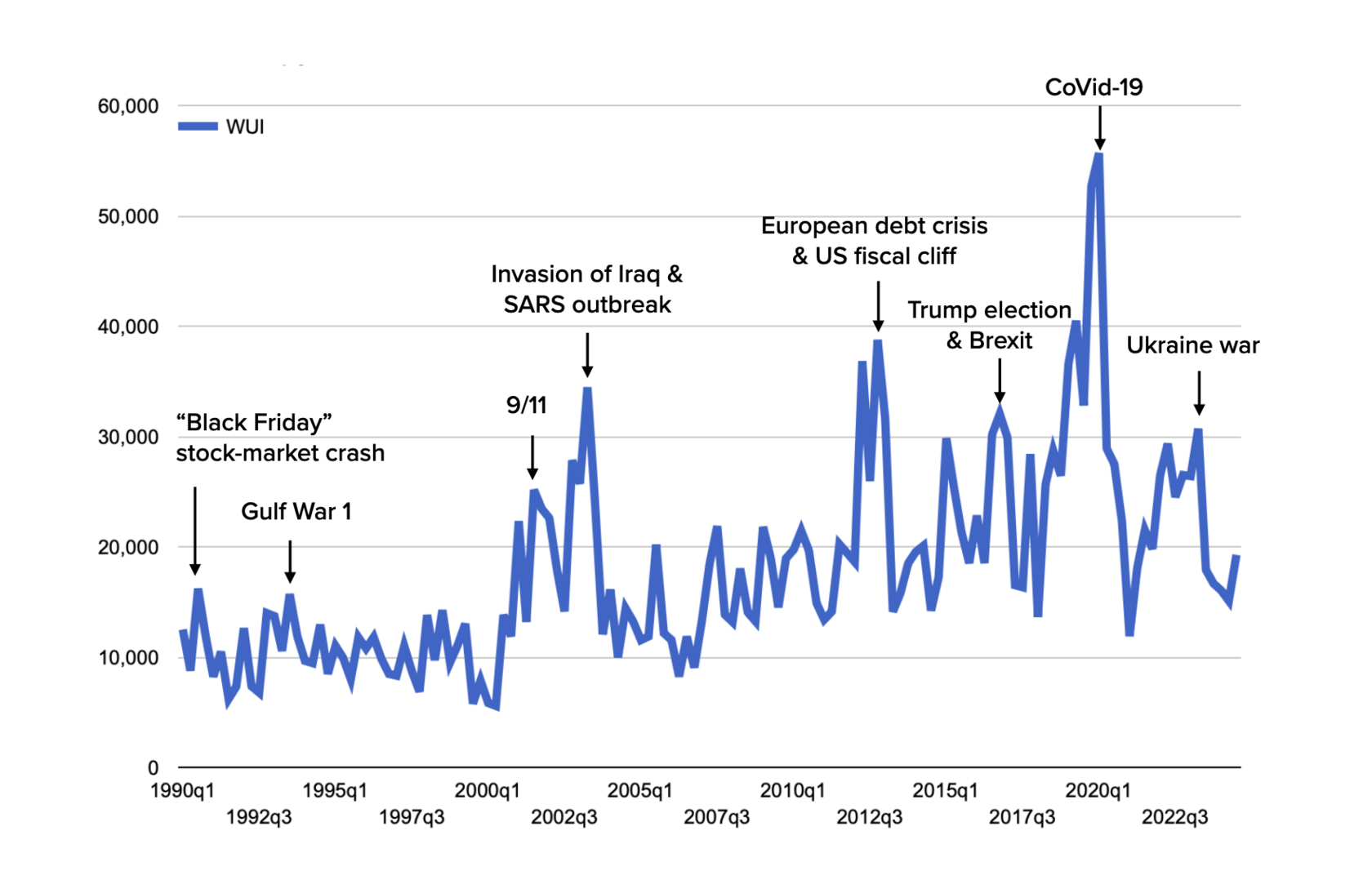

The World Uncertainty Index1 suggests that global uncertainty is rising (see fig.3). Political turbulence, financial crashes, wars and natural disasters make the future unpredictable, yet even a cursory glance at history shows that such events are not new. So why does it feel like uncertainty is running out of control today?

The difference is that our modern ‘Age of Information2’ provides us with unprecedented amounts of data to make sense of the world, but also unparalleled levels of ‘noise’ — interference and distortion that makes data:

The difference is that our modern ‘Age of Information2’ provides us with unprecedented amounts of data to make sense of the world, but also unparalleled levels of ‘noise’ — interference and distortion that makes data:

- Unreliable — as questionable sources affect credibility.

- Ambiguous — open to multiple interpretations.

- Complex — challenging to integrate cohesively.

- Missing — unavailable or inaccessible when needed.

This is the modern information paradox: the more data, the more noise amplifying our uncertainty.

Fig.3: World Uncertainty Index (WUI) 1990—2024(Q3)

The WUI measures the frequency of “uncertain” (or its variants) in Economist Intelligence Unit country reports. Higher number means higher uncertainty.

Uncertainty Causes More Stress Than Pain

Avoiding uncertainty is instinctive to humans and there are good evolutionary reasons for this — it was better our ancestors assumed the rustling of the grass behind them was a predator and be wrong, than assume it was just the wind and be wrong. However, as an experiment at University College London demonstrated3, uncertainty can create extreme anxiety in humans and this can affect how we act.

The university research team divided their volunteers into three groups. They told each of them that they would play a computer game where they’d have to turn over rocks and if there was a snake underneath a rock they’d receive “a mildly painful electric shock on the hand”. The first group was told there were no snakes under any of their rocks (0% chance of getting a shock). The second group were told there were snakes under half their rocks (50% chance of getting a shock). While the final group was told there were snakes under all their rocks, so they’d be shocked every time. As the volunteers played, the researchers measured their stress levels and the results surprised them. Volunteers in the first group, with a 0% chance of getting a shock were, unsurprisingly, the least stressed. Yet, volunteers in the second group, those who got a shock 50% of the time, were significantly more stressed than those in the third group who got a shock every time. “The most stressful scenario” the researchers found “is when you really don't know. It's the uncertainty that makes us anxious” rather than the inevitability of pain.

Acute stress from uncertainty makes people more susceptible to those who speak with certainty: economists who forecast future growth to two decimal places (despite routinely getting it wrong); futurists who declare the technologies that will re-shape our future (despite continually missing the ones that do); and management consultants whose pretty slides explain how your company’s fortunes will experience a smooth upward curve, if only you adopt their recommended course of action (despite no-one being in control of all the variables needed to delver this). ‘Peddlers of certainty’ — “best practice” pushers, case study dealers, powerpoint evangelists, backed up today by even bigger datasets and the power of AI — provide a comforting illusion4 that gives many leaders what they most desire: certainty5.

The pursuit of certainty fuels the annual planning cycle in organisations. Executives and their teams perform the ritual steps — gathering and analysing data, brainstorming initiatives, determining strengths and weaknesses — to produce a ‘strategic plan’ that (supposedly) will determine the organisation’s performance for the year ahead. The only uncertainty is the execution of these well-laid plans, which has given rise to a cottage industry of KPI (key performance indicators) setters and OKR (objectives and key results) formulators that promise to eliminate the variance between one’s best-laid plans and the messy reality of the real world.

This ‘assembly line’ approach (where known inputs produce knowable outputs) worked well in the previous ‘Industrial Age6’ as the main production assets were large scale, predictable machines. But in the modern ‘Age of Information’ — where the key production assets are knowledge workers, who turn abundant data into productive information — certainty and control is mirage. Cheap, ubiquitous computing and technological advances have reduced barriers to entry in many industries, leading to new competitors emerging from every corner of the globe, influencing consumer habits and accelerating the rate of change. With tightly-coupled supply chains amplifying shocks globally at devastating speed, businesses are getting disrupted today before they’ve even pinned their ‘strategic plans’ to the conference room wall7. Yet ‘strategic planning’ not only remains the dominant way of “managing the organisation’s future but [for many] the only conceivable one8”.

Problems With Strategy Today

Perhaps the most important finding from the University College experiment into how humans respond to uncertainty was the “potential benefit” of stress. “People” the researchers found “whose stress responses spiked the most at periods of greatest uncertainty were better at judging whether or not individual rocks would have snakes under them”. In other words, the more stressed people became the better their choices. Stress appears to be an evolutionary mechanism for heightening our awareness of what we should, or should not do in unpredictable conditions: “Appropriate stress responses might be useful for learning about uncertain, dangerous things in the environment” increasing our ability to survive and thrive in a volatile world.

‘Learning about our environment’, how it’s changing and having ‘better judgement’ about the opportunities and threats we face is the essence of strategic thinking. Yet, rather than using the heightened awareness stress triggers so we act more effectively in an uncertain world, many organisations prefer to create plans that try to predict the future in order to reduce stress. They focus on what they have in their control, such as costs, as they can decide themselves how much to spend and on what. Departments submit lists of initiatives to tap into their fair share of the budget, often basing these on the past practices of others as that provides ‘evidence’ about the returns on investment the organisation can expect. Initiatives from across the entire organisation are centrally collated and revenue projections extrapolated from them to produce a set of targets everyone must now chase down (even though plans heavy on copying what others have done provide the business with no competitive differentiation and makes success that much harder to deliver).

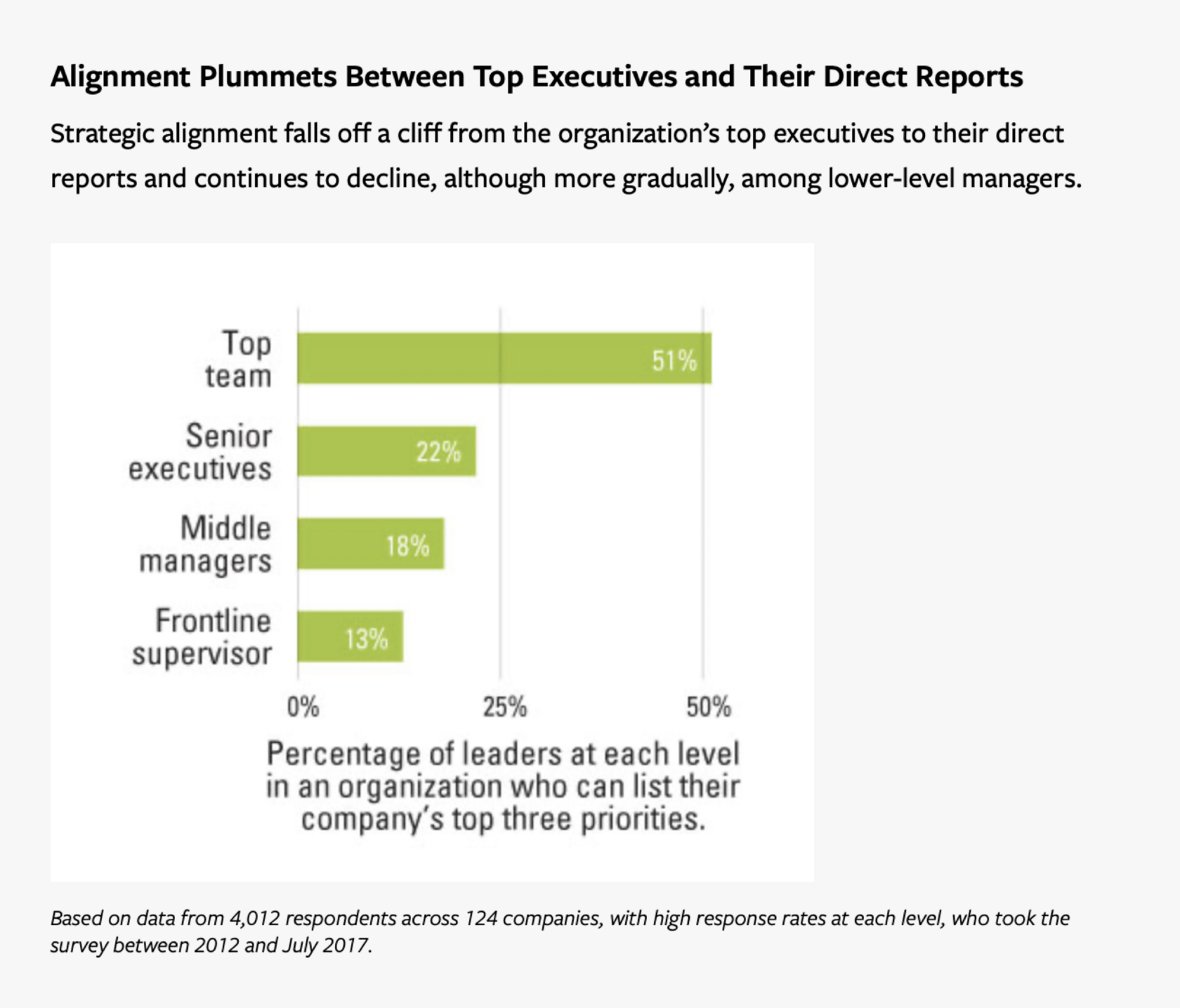

The ‘thinkers’ who created the ‘strategic plan’ now roll it out to the ‘doers’ to implement it. KPIs become targets, with good performance rewarded with bonuses and under-performance punished by their absence. Yet, performance is not measured against the unfolding reality of the present, but against the guesses made in the past and set in the plan. As a result, average performance in better-than-forecasted market conditions is often rewarded, whilst exceptional performance in worse-than-expected market conditions is unfairly penalised. The need to hit right targets encourages departments to be heads down all year, focused on their own initiatives, believing that someone, somewhere is integrating these into a coherent strategy that will help the organisation achieve it’s overall aim or mission. This is why most people — from frontline staff through to senior executives — can’t name their organisation’s top three strategic priorities (see fig.4). Shockingly, around half of ‘top teams’ — the ‘thinkers’ supposedly responsible for creating strategy — can’t name these either; suggesting there is rarely a purposeful strategy in play in many organisations.

Fig.4: No One Knows Your Strategy — Not Even Your Top Leaders

Unfortunately, the 2020s revealed that no amount of planning — regardless of how elaborate or data-driven it is — can predict the sharp discontinuities that impact us so dramatically. Furthermore, plans that bind us to a world we want to see, make us blind to the world that is actually unfolding, hindering our ability to adapt in time. Planners find it hard admit that their plans are faulty and the resources spent creating them wasted, so ‘sticking to the plan’ becomes an act of faith, a belief that, in the “hundreds of pages of analysis” and the “flowery prose that supplements the numbers in the budget” there is something that’ll lead them to success, even though the reality is often that, the entire planning cycle was just “a colossal bureaucratic waste of time9”.

The frustration with the limitations of ‘strategic plans’ have fuelled a new obsession with rigorous execution, epitomised in the often-quoted words of JPMorgan Chase CEO, Jamie Dimon, who said: “I’d rather have a first-rate execution and second-rate strategy any time than a brilliant idea and mediocre management”.10 While relying on better execution alone sounds admiringly pragmatic and action-oriented, it brings its own problems:

“When Hewlett-Packard, announced disappointing results in August 2004, CEO Carly Fiorina stated, “The strategy is the right one. What we failed to do is execute the strategy.” Her explanation sounded reasonable, and no one questioned her when she swiftly replaced a few key executives — it looked like an appropriate step to improve execution and raise company performance. Curiously, when Fiorina herself was fired just six months later in February 2005, a company spokesperson repeated the same line: HP was following the right strategy, but the chief executive was replaced because the board of directors wanted better execution! Again, it all sounded reasonable, and no alarms were raised about the company’s basic choices. Six weeks later, when Mark Hurd was hired as the new CEO, Hewlett-Packard stuck to its message, announcing that it had “picked Mr. Hurd because of his execution skills.” And therein lies the problem: It’s always easier to bang the drum about execution than to address fundamental questions of strategy. It’s always easier to insist we’re going in the right direction but just need to run a little faster; it’s far more painful to admit that the direction may be flawed, “because the remedies are much more consequential11”.

Rather than creating flawed plans that aim to reduce our stress in an uncertain world, we can embrace uncertainty and use the stress it triggers to improve our awareness and judgment about what really matters — customers. Customers are beyond our control — we can’t tell them who to buy from in the same way we can tell internal departments what to spend or not12. But we can make choices about which customers to target, which needs of theirs to focus on, and how we can satisfy those better than the competition so customers buy from us and not them. Customers don’t care about our internal initiatives — they only care about what we can do for them and, if we want to be successful, that’s what we should care about too. We only create value for ourselves when we create something that others value enough to buy from us.

It’s time to stop making strategic plans that focus on satisfying our desires to be stress-free as this is harming our ability to think and act strategically. We only need to remember that, to succeed in an uncertain world, we don’t need to make the right choices — we just need to make better choices than our rivals.

2 Starting around 1971 when the Intel microprocessor was announced.

3 “Computations of uncertainty mediate acute stress responses in humans”. Nature Communications. March 29, 2016. Discussed in ScienceDaily https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/03/160329101037.htm

4 Before the 2018 football world cup the Swiss investment bank, UBS, ran 10,000 simulations and predicted that Germany to win the world cup https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-17/germany-will-win-the-world-cup-ubs-says-after-10-000-simulations

Then the US investment Goldman Sachs used AI to run 1 million simulations and predicted that Brazil would win the world cup in 2018: https://nordic.businessinsider.com/world-cup-predictions-pick-to-win-it-all-goldman-sachs-ai-model-2018-6?r=US&IR=T

Neither Germany nor Brazil even made it to the semi-finals, so Goldman Sachs re-ran its simulations with the four teams remaining and predicted Belgium would win it. Despite having a 1 in 4 chance Belgium also failed to make it to the final, which was won by France who beat Croatia: https://www.businessinsider.com/world-cup-predictions-goldman-sachs-ai-model-belgium-england-final?op=1

For a summary of this see: ubs-commerzbank-predict-germany-would-win-world-cup-wrong

Then the US investment Goldman Sachs used AI to run 1 million simulations and predicted that Brazil would win the world cup in 2018: https://nordic.businessinsider.com/world-cup-predictions-pick-to-win-it-all-goldman-sachs-ai-model-2018-6?r=US&IR=T

Neither Germany nor Brazil even made it to the semi-finals, so Goldman Sachs re-ran its simulations with the four teams remaining and predicted Belgium would win it. Despite having a 1 in 4 chance Belgium also failed to make it to the final, which was won by France who beat Croatia: https://www.businessinsider.com/world-cup-predictions-goldman-sachs-ai-model-belgium-england-final?op=1

For a summary of this see: ubs-commerzbank-predict-germany-would-win-world-cup-wrong

5 https://www.managementtoday.co.uk/why-need-turn-back-silver-bullet-solutions/opinion/article/1873247

6 Which was the Fourth Industrial Revolution if we consider the first as the Industrial Revolution (starting in 1771); the second Age of Steam and Railways (1829); the third the Age of Steel, Electricity and Heavy Engineering (1875); the fourth the Age of Oil, the Automobile and Mass Production (1908); meaning the current Age of Information and Telecommunications, starting in 1971 when the Intel microprocessor was announced in Santa Clara, California is the fifth Industrial age. Source: Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital. The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages. Carlota Perez (p.11)

7 “The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men,

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!”

— Robert Burns

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!”

— Robert Burns

8 Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. Henry Mintzberg (1994) p.60

10 Quoted in https://hbr.org/2010/07/the-execution-trap

11 The Halo Effect. Phil Rosenzweig (2007) p315