For anyone who believed the world was a predictable place, where plans could be made and executed easily, the 2020s would have come as a nasty shock. Yet, anyone holding such a view could not have been paying much attention to even the events of our ‘short’ 21st century — with planes ‘coming out of a clear blue sky’ sparking global wars, sub-prime loan defaults on the U.S. West coast triggering a global financial crisis, and a tiny virus bringing the global economy to a standstill — all proving Edward Lorenz right1: small causes do lead to large, unpredictable outcomes. This is why the the future remains a stubbornly unpredictable place, where the only constant is change. To survive and thrive, we must become better at adapting to change.

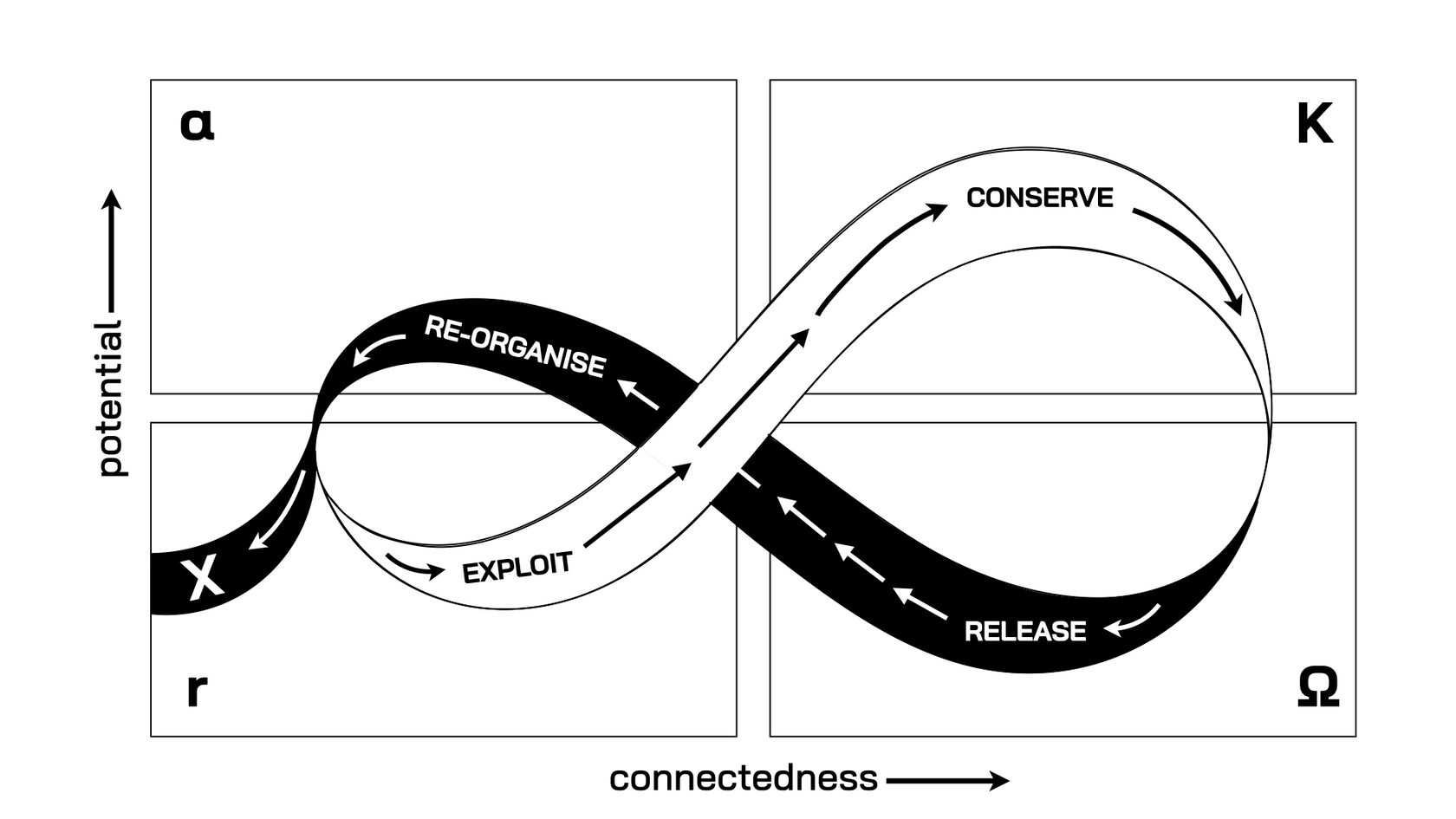

Fig.5: The Adaptive Cycle

A powerful model for understanding how systems change is ‘The Adaptive Cycle’ by Holling and Gunderson (20022) that outlines four key stages:

- Conserve (K): In natural ecosystems or human systems, (such as industries) a few large players, the apex predators or large corporations dominate. The rest of the system organises around them, in complex predator-prey dynamics or tightly inter-connected supply chains. As long as resources, such as food, talent and capital remain abundant, the system retains high potential for growth. But its excessive interconnectedness creates rigidity, making the system fragile and vulnerable to shocks.

- Release (Ω): When a major external shock strikes, such as a natural disaster or an economic collapse the system is thrown into chaos. The disruption spreads rapidly through its tightly woven connections and its rigidity prevents it adapting quickly enough. Jack Welch once famously warned that, “if the rate of change on the outside exceeds the rate of change on the inside, the end is near” and the system starts to disintegrate, releasing all its accumulated potential, such as resources and talent.

- Re-organise (α): A period of great uncertainty follows and to survive, players must explore and experiment with new approaches. Those who rely on the old ways that are quickly disappearing start to become maladapted, unable to function effectively in the changed conditions, hastening their own extinction (X). As they disappear, competition for resources decreases, benefitting those who adapted.

- Exploit (r): Those who successfully reorganised now thrive, gradually becoming the new dominant players. As the system starts to reorganise around them, interconnectedness increases again, bringing the same benefits but also the same rigidity and vulnerabilities. However, innovation continues to be developed at the periphery, the new ideas and approaches that will thrive when future disruptions hit. It’s this “diversity retained in residual pockets preserved in a patchy landscape3” that ensures the system’s long-term resilience, allowing it to evolve not in spite of change, but because of it.

The classic example of the Adaptive Cycle in action is pre-historic Earth, which was once covered in lush mega-fauna, conditions that dinosaurs exploited (r) best, often growing to enormous sizes. Able to eat whatever — or whoever — they wanted, they secured their position as the planet’s apex species, a dominance they conserved (K) for millions of years. Then a shock hit. Sixty six million years ago a comet is believed to have struck Earth, collapsing the ecosystem and wiping out 75% of all species. With the system’s accumulated resources now released (Ω) species had to re-organise (ɑ) to exploit new, ‘unoccupied ecological real estate’ to survive. None did this better than the early mammals.

Mammals first appeared approximately 200 million years ago, around the same time as the dinosaurs. Occupying a much lower rung on the food chain, mammals had to rely on scarce, unpredictable food sources that dinosaurs ignored, which meant they remained small. However, their small size and highly-evolved foraging skills became advantages when the conditions changed. Smaller creatures are more energy efficient and require less food to survive. Constant foraging also developed flexibility, making them more adept at finding food and less selective about what they ate. In contrast, the dinosaurs at the top of the food chain had thrived on an abundance of highly-specialised foods, but their resulting massive frames were reliant on a lush ecosystem that was now disappearing. The gradual extinction4 of the dinosaurs made way for new apex species on the planet to arise — the mammals, including eventually us humans. Yet, the Adaptive Cycle is ‘more than just a metaphor5’ for describing change in natural systems — it also explains the rise and fall of industry giants.

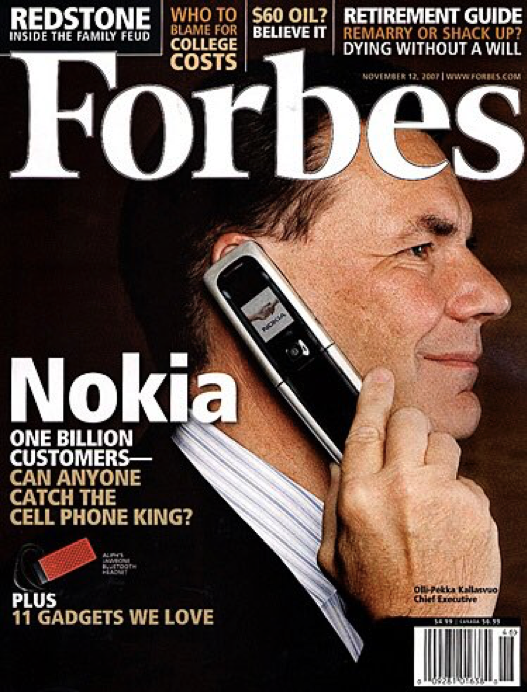

On their November 2007 cover, Forbes posed the question: With “one billion customers — can anyone catch the cell phone king?” At the time, Nokia dominated the global mobile phone market, with around 50% of all devices sold being theirs. However, earlier that year, a ‘comet-like’ event had struck the Symbian system Nokia relied on — Apple’s launch of the iPhone.

Fig.6: ‘Can Anyone Catch The Cell Phone King?’ Forbes (November 2007)

The iPhone exposed the limitations of its rigid Symbian system and shattered Nokia’s dominance as they couldn’t adapt quickly enough to the possibilities released by Apple — touchscreens, apps, and third-party integration. These innovations ushered in a new world previously thought inconceivable — mobile retail, banking and living — redefining customer expectations and re-shaping entire industries. The new possibilities attracted talent — innovators eager to explore tomorrow’s world, rather than maintaining yesterday’s — and organised themselves in radically different ways, such as flexible working and agile teams to exploit opportunities more effectively. Financial capital — driven by the search to maximise future returns — was an early adopter, investing heavily and reinforcing these emerging changes. Creative destruction had been unleashed6.

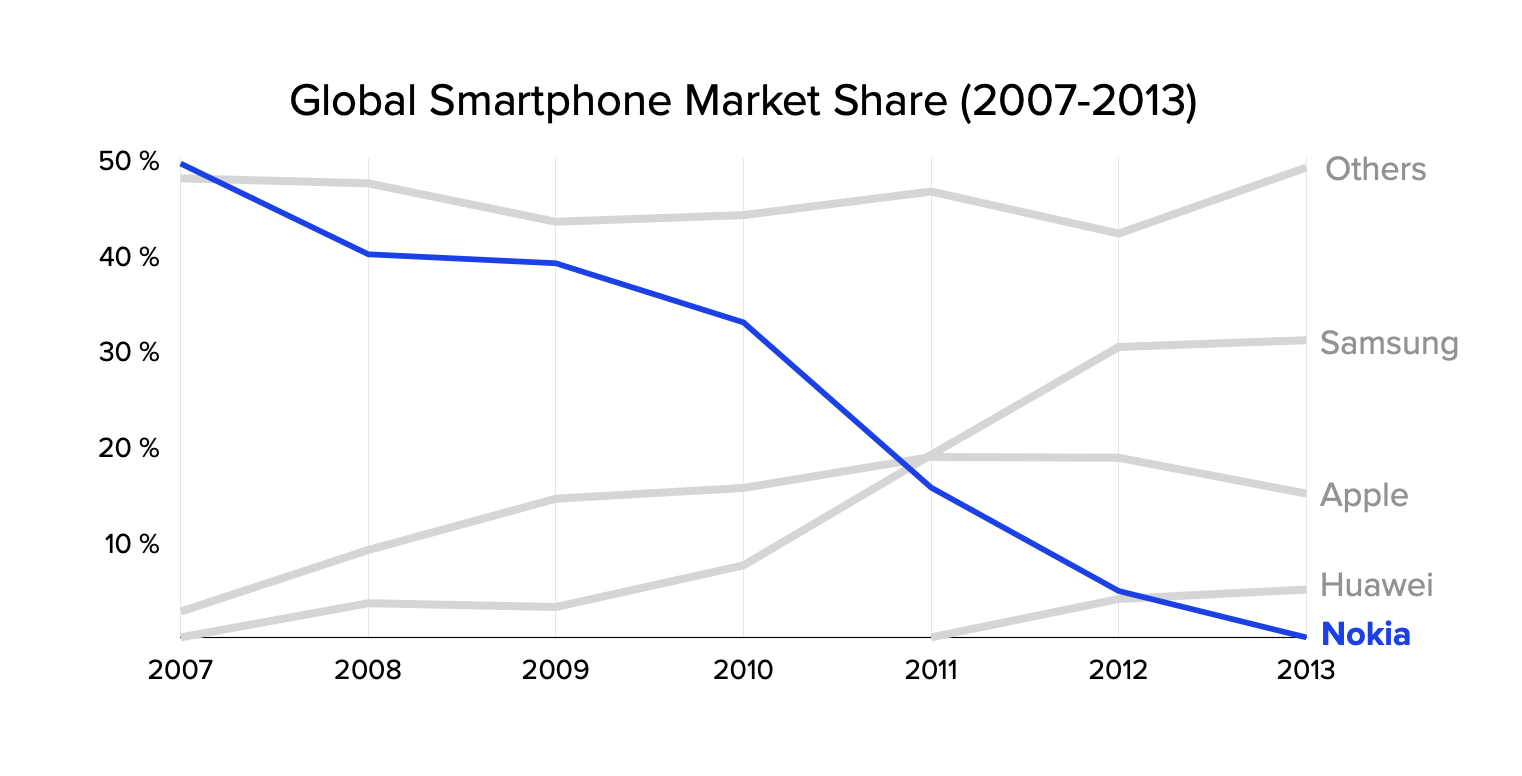

At first, Nokia underestimated the magnitude of this shift, as it was happening on the periphery of their world. They focused instead on conserving the massive Symbian system and trying to extend its reach. These were the early years of the great Chinese economic boom and Nokia’s executives were targeting their next billion customers. However, even China’s new aspirational migrant class7 were embracing the new ways of shopping, banking and living and Nokia belatedly recognised a massive shift had occurred. They tried to go ‘all-in’ on the new but found the talent and finance they needed were in short supply — already occupied by smaller, faster early movers. Being late to the biggest game dealt a tremendous blow to Nokia’s reputation as a market leader and, within just seven short years, the market share of the ‘cell phone king’ had fallen to essentially zero. Unable to re-organise or exploit the potential in the new ecosystem Nokia’s fate mirrored that of the dinosaurs — only much, much faster.

Fig.7: The Precipitous Fall of the “Cell Phone King”

When future historians write the history of the 2020s, they may see a series of comet-level shocks that impacted every industry in our tightly-coupled global economic system and how the dominant players tried to conserve the status quo by promising to ‘build back better’. However, as the Adaptive Cycle’s one-way arrows show, success comes from harnessing the pioneering new ideas and methods — often the ones dismissed in the past — for once potential has been released and pioneering talent re-organises itself to exploit the emerging opportunities, there’s no going back. The system evolves and everyone is left with a stark choice: adapt or die! We embrace change and develop, or we resist evolution and go the way of the dinosaurs and the ‘cell phone king’. “The single most important factor for any company in this time [therefore] will be the imagination and willingness of executives to adapt to change8”. What kind of executive you are, or what kind of executive you work for, is going to matter greatly moving forward.

1 See introduction — Why Best Practices Hold You Back.

2 Resilience and Adaptive Cycles. C. S. Holling and Lance H. Gunderson (2002) http://www.loisellelab.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Holling-Gundersen-2002-Resilience-and-Adaptive-Cycles.pdf

3 Resilience and Adaptive Cycles. C. S. Holling and Lance H. Gunderson (2002) p35

4 With the exception of the avians, which evolved into modern birds. This process took around 10 million years.

5 The adaptive cycle: More than a metaphor. Sundstrom and Allen (2019) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1476945X1830165X

6 This will be explored in more depth in part three.