There are two types of mistakes: mistakes of commission — things we did but shouldn’t have — and mistakes of omission — things we should have done but didn’t. Mistakes of commission are visible; we can see what went wrong. But the blame game that often follows discourages people from taking risky action, since failure can damage their reputation or career. This leads to more mistakes of omission — missed opportunities that are harder to spot and rarely accounted for.

In competitive markets, where constant external change demands action to stay relevant, this reluctance to act can become dangerous. Inertia — resistance to change — can be fatal. And ironically, it’s often the most successful organisations that are most vulnerable, as they feel they have the most to lose.

So, let’s explore three rules of the game that deal with the deadly threat of inertia — and what we can do to overcome it.

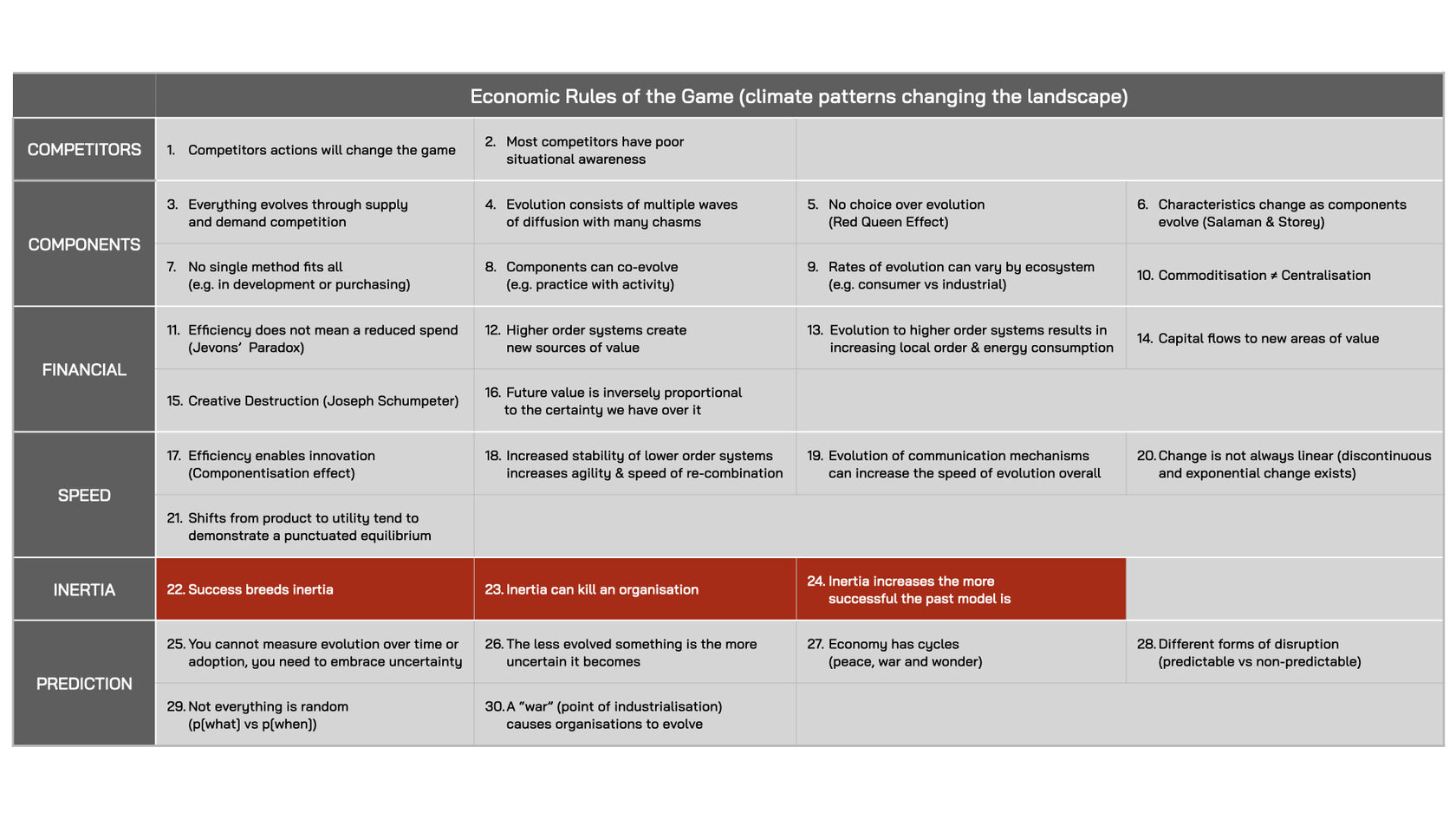

Fig.127: The Economic Rules of the Game and Inertia

Rule #22. Success Breeds Inertia

Inertia, or resistance to change, is rooted in the psychology of individuals and even entire cultures, as we have a natural aversion to the uncertainty inherent in the new1. Resistance can sometimes be useful, especially when it involves pointing out potential flaws in new courses of action, thereby preventing mistakes of commission. However, much inertia springs from a fear of losing power or status. Why, for example, should we take on seemingly unnecessary risks when there is no guarantee of success? Why risk losing prestige by attaching our reputation to a new product or service that might, at best, cannibalise our current offerings and, at worst, fail? Why would employees switch from a career path they’ve carefully cultivated to take on something they’re less experienced or equipped to pursue?

Inertia, therefore, is widespread within organisations — amongst top management who resist any changes to a system they’ve managed to reach the top of, or among more junior staff who fear failure and the consequences this may have for their prospects. Inertia also comes from outside the organisation — customers who seem happy to keep buying the same products or services, or suppliers that project their own inertia by reminding you ‘this is the way things are done’ — reinforcing the organisation’s resistance to experimenting with anything new. However, as noted above, the Red Queen Effect means we have no choice about change, making resistance the quickest path to failure (rule #5).

Customer behaviour can change rapidly when a new technology or product comes to market that offers something faster, cheaper, better. Organisations that convinced themselves they didn’t need to change are suddenly forced to play catch-up — but deeply entrenched inertia means they’ve failed to develop the requisite variety of responses needed to react swiftly2. This was the position Nokia faced in 2007 after Apple launched the iPhone.3 Nokia had the data proving customers loved their products and showed no indication that they would switch. This lulled them into a false sense of security that Apple would take years, if not decades, to surpass them — giving them time to react, if that even proved necessary. But this change was a punctuated equilibrium (see rule #21) and Nokia’s demise was rapid and catastrophic.

***

To overcome inertia and prepare the organisation to respond swiftly and effectively to change requires an understanding of the sources of resistance. Is this the healthy type of resistance that prevents the organisation from making mistakes of commission — embarking on the wrong course of action — and comes from experienced professionals identifying potentially fatal flaws in new ideas and demanding further improvements before committing to them? Or is it the unhealthy type of resistance that shuns anything new, as it threatens the temporary status quo that benefits certain individuals (at the expense of the organisation)? This leads not only to mistakes of omission — action not taken, due to fear of uncertain outcomes — but prevents the organisation from seeking out or experimenting with potentially new sources of value, leaving the door open to bolder rivals.

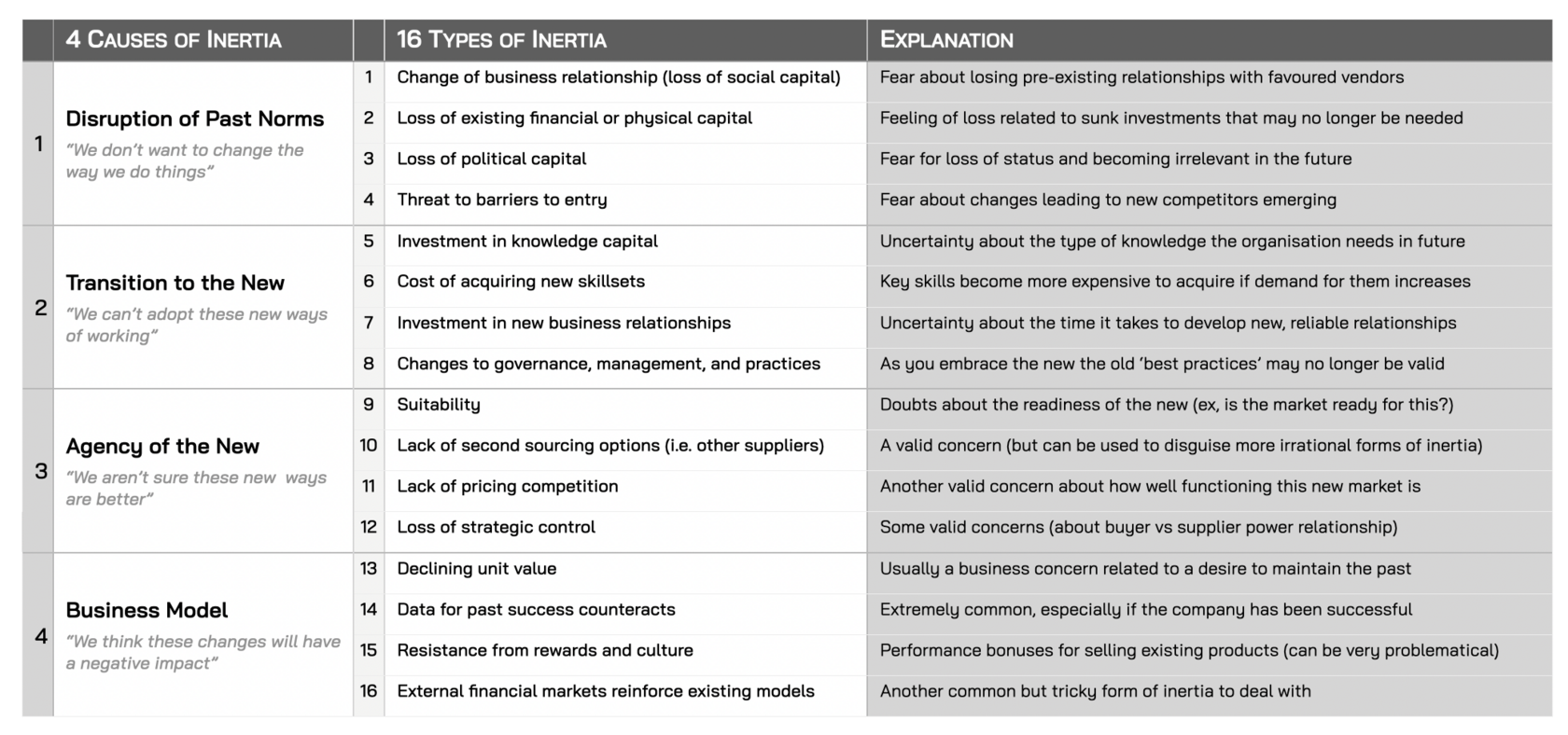

Simon Wardley identified 16 different types of inertia, grouped into four main causes:

- Fears around disruption of past norms — “we don’t want to change the way we do things” (unhealthy)

- Fears about transitioning to the new — “we can’t adopt these new ways of working” (unhealthy)

- Concerns around the agency of the new — “we aren’t sure these new ways are better” (healthy)

- Concerns about the business model — “we think these changes will have a negative impact” (healthy)

Fig.128: Four Causes and 16 Types of Inertia

The more successful an organisation is, the deeper these 16 types of inertia can be rooted. Often this is because they have data to support their arguments — “we have one billion customers, people love our phones”. But data is always about the past, and the rules of the game are about how the future is unfolding. Resisting change can deliver short-term tactical wins — “let’s keep doing what we’ve always done and hit the budget targets for this year” — but lead to long-term strategic defeat as the organisation fails to adapt in time.

We will explore the countermeasures you can deploy to overcome these 16 types of inertia in Part Four.

Rule #23. Inertia Can Kill An Organisation

Nokia, of course, was not the only example of a large, successful company killed by inertia: both Sears and Toys ‘R’ Us collapsed as they stuck to brick-and-mortar stores while retail went digital (inertia type #2, fig.128); RIM Blackberry wrongly believed their customers would always want a fixed keypad on their phones (inertia type #4); Blockbuster remained wedded to a business model based on late fees (type #15); and GE continued relying on past success in certain markets that prevented it from adapting quickly enough in a rapidly-changing world (inertia type #16).

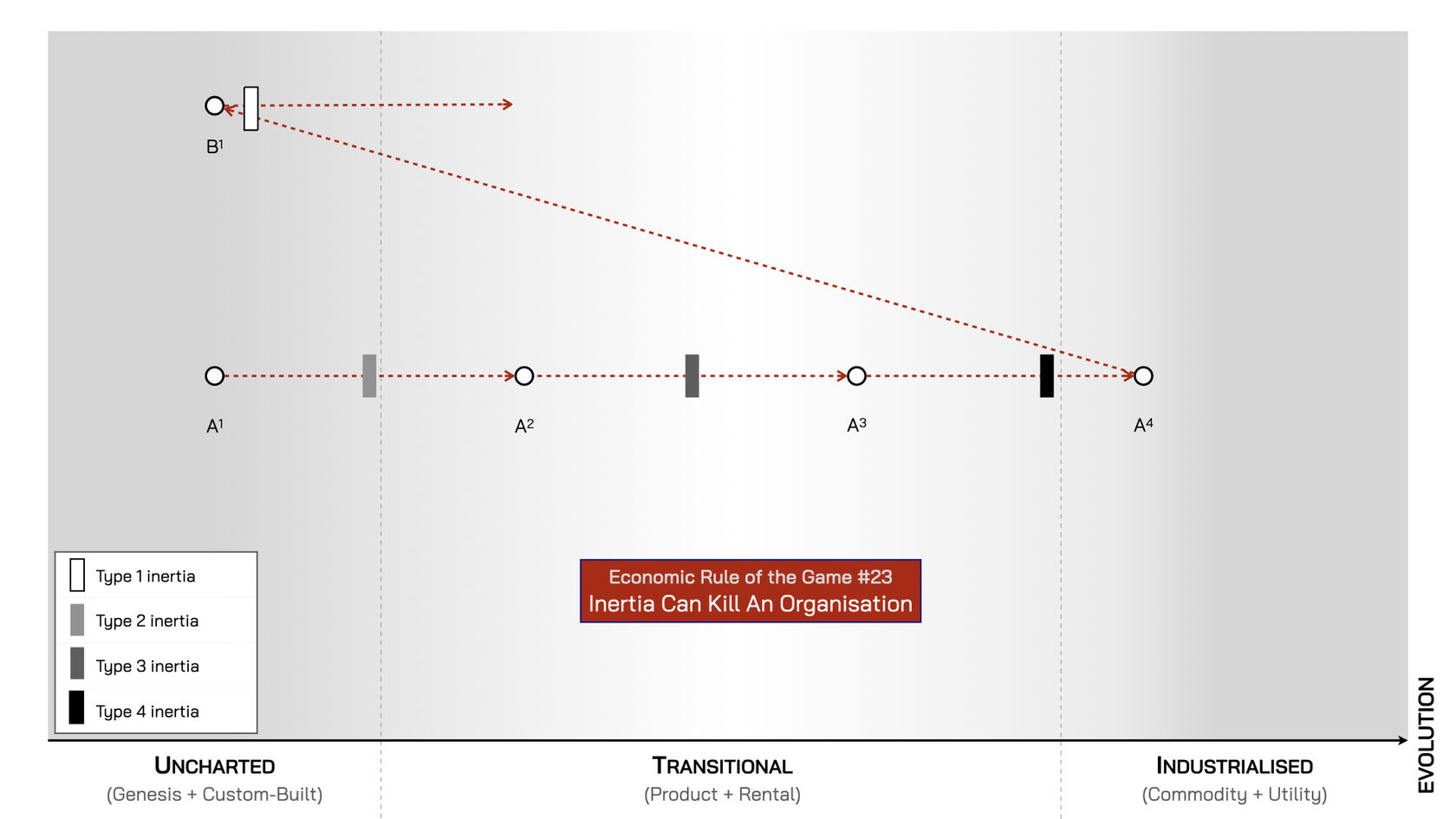

Inertia can be most deadly when a component crosses a stage of evolution (see fig.129). Components crossing from the uncharted space into the transitional space must overcome much type 2 inertia — related to concerns over transitioning to the new (investment in new knowledge, skills, relationships and practices that are still uncertain).

As components evolve through the transitional space, they become harder to ignore, but must overcome more type 3 inertia — concerns with the agency or suitability of the new (is the majority market really ready for this? Will we get locked into suppliers if we make this move? How will that change our bargaining power? And will that lead to a diminishing of our freedom to act?).

Once components are widespread on the market and on the cusp of becoming commodities — as they’re increasingly difficult to differentiate from those of rivals — type 4 inertia must be overcome. Here, the concerns relate to current business models (how will we deal with declining unit value if this product becomes a commodity? Can we just squeeze a bit more value out of it first — the market seems to think so? Oh god! What will happen to my bonus if we don’t hit targets this year?). But, as we’ve noted above (rule #5) resistance to evolution is futile.

When a component finally industrialises we know that higher-order systems that create new sources of value will be built on top of them (rule #12), while talent and capital flow to them, destroying the old (rule #15). Yet, for many, this triggers type 1 inertia — concerns related to the disruption of past norms (a loss of social capital as new business relationships need to be formed, sunk investments may need to be written off, status as a leader will need to be re-established and there’s little one can do at the moment to stop others from competing against you in this new space on a more level playing field).

Fig.129: Organisations Get Stuck Behind Multiple Barriers of Inertia

Organisations need to be aware of inertia internally as failure to address the causes of this can allow resistance to fester and ultimately hold the organisation back from adapting in time, thereby threatening its entire existence. However, knowing that all organisations are susceptible to inertia — as all organisations are collectives of people and humans have a natural aversion to uncertainty (with some cultures having more acute levels than others) — means that one can use inertia as a weapon to inflict harm on rivals by fuelling their resistance and pushing them down the path of self-destruction. This is a specialised form of strategic gameplay that we will explore in Part Five.

For now, we can conclude that inertia can be a mortal threat to organisations if it prevents them from adapting as fast as their Landscape is changing.

Rule #24. Inertia Increases The More Successful The Past Model Is

Successful organisations have a high bar for success, and this can amplify their inertia. New ventures must show exceptional potential before they even register on the radar of multi-million or billion-dollar organisations. Executives prefer the certainty of the present — continuing to do what we’ve always done so well in order to satisfy the market, unlock those bonuses, or fully cash out.

Success is backed up by data and narratives that explain why the past will stretch long into the future: ‘Digital won’t replace physical — people want to feel our products in their hands’. ‘Electric won’t replace gas — people want to feel the roar of the engine’. The more successful an organisation is the more data and narratives it can produce to support the status quo. Yet, as the Red Queen Effect (rule #5) reminds us, those who can’t — or won’t — adapt quickly enough will be out-competed by those that do, no matter who has been successful in the previous era4.

Inertia is why many radical industry changes often come from outsiders — those unencumbered by past success and more willing to experiment with the new. Netflix was a DVD-by-mail company before it revolutionised the streaming industry; Apple was a ‘niche computer manufacturer’ before it transformed the mobile phone industry; and Amazon was just an ‘online bookseller’ before it created the cloud computing market — leaving yesterday’s giants unable to respond (see fig. 130).

Like the victory of the smaller, faster-moving prehistoric mammals over the large, slow-moving dinosaurs, the entities best organised to adapt are the ones that exploit the future’s potential most effectively — often because they have less to lose and everything to gain, unlike their more successful counterparts.

Fig.130: Market Capitalisation Amazon vs. IBM $billions (Jan 2006 — Jan 2022)

4 See the Adaptive Cycle in chapter two — Adapt or Die