What lessons could British manufacturers in the US motorbike market have learned from the Eastern approach to strategy to face down the competitive threat from an up and coming player like Honda? Fortunately, for those who love case studies, we don’t have to speculate. A decade later Honda was the incumbent whose dominance in their domestic motorbike market was being challenged by the up and coming Yamaha. What became known as the ‘Honda-Yamaha war’ provides insights into how the strategic game is played in the East.

In 1981, Yamaha opened an enormous new factory that, when running at full capacity, would make them the world’s largest motorbike manufacturer. The problem was, Honda held this title and weren’t going to relinquish it without a fight. Facing a massive competitive threat, market leaders often choose to defend (or conserve) their position by launching an efficiency campaign to cut costs and maintain profitability; or lobby the government to seek protections, emphasising their importance as a major employer and tax contributor.

Yet, defensive moves lack any compelling vision of the future, which can be fatal for a market leader as it hinders their ability to attract the top talent or sufficient capital needed to mount an effective response. Defensive moves make the company look like a “dead player — incapable of doing new things”1 — which is a damaging image for a market leader. But, as we’ve already seen2, Honda was a “live player — able to do things they have not done before”. Instead of defending their position they went on a massive counter-attack with the battle cry: “Yamaha wo tsubusu!” (“We will crush Yamaha!”).

Direct and Indirect Attacks

Attacks can take two forms: direct or indirect. Building an even bigger factory would have been a direct attack, but this would have also risked oversupplying the market, potentially triggering a catastrophic price war, damaging profitability across the industry and resulting in massive layoffs. Honda did make some direct attacks — cutting prices, outspending Yamaha on marketing, and flooding distribution channels — but these moves were part of a broader indirect attack that created “the opportunity for real growth3” at the same time.

In a whirlwind 18-months Honda launched a huge variety of new motorcycle models — 113 in all, nearly double their previous lineup of 60 (the same as Yamaha’s). Each new model featured ever more sophisticated technology and Honda actively listened to what users thought about these motorbikes, before incorporating those insights into subsequent iterations. This massive, real-time testing campaign not only enabled Honda to learn about customer preferences, but to start shaping them as well. Honda “succeeded in making motorcycle design a matter of fashion, where newness and freshness [were] important to customers4”.

Yamaha simply couldn’t keep up. In response to Honda’s 113 new models, Yamaha launched just 37 and soon, “next to Honda’s motorcycles, Yamaha’s bikes [began to look] old, out-of-date, and unattractive5”. Sales plummeted and they even struggled to sell motorbikes below costs, leading to soaring inventory costs. Eventually, Yamaha had to make a humiliating public climb-down — “We want to end the H-Y war. It is our fault” declared Eguchi, Yamaha’s president. “We cannot match Honda’s sales and product strength. Of course there will be competition in the future, but it will be based on a mutual recognition of our respective positions6”.

Honda’s successful indirect attack came at a cost and significant investment would be required to get them back on a ‘stable footing’. However, “so decisive was its victory that Honda effectively had as much time as it wanted to recover. It had emphatically defended its title as the world’s largest motorcycle producer and done so in a way that warned Suzuki and Kawasaki not to challenge that leadership. Variety had won the war7”.

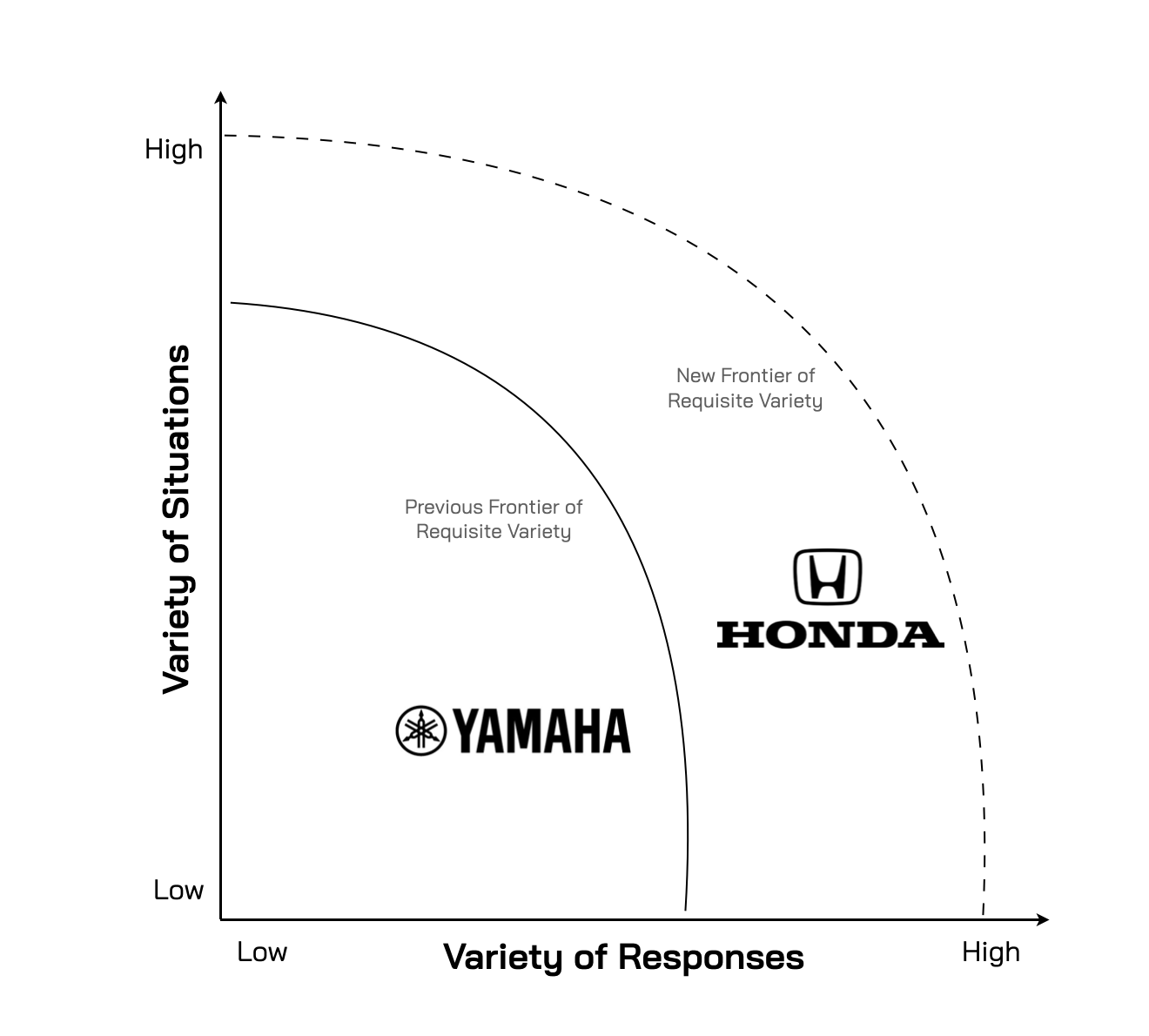

Fig.14: Honda Pushed the Frontier of the ‘Requisite Variety’ of Responses Needed to Crush Yamaha

Honda were able to respond so swiftly to Yamaha’s threat as they had spent years embracing new ideas and technologies, as well as experimenting with new practices (like flexible factories). They had built a requisite variety of potential responses8. Honda also understood (as did Pal’chinskii9 before them) that new technology alone is insufficient for victory. A large part of their success over Yamaha came from how they tapped the increased flows of information coming in from customers through effective feedback loops, enabling them to quickly select what was working in their local context (Pal’chinskii’s third principle) and continually create new motorbikes that better satisfied customers’ evolving needs. Each new motorbike launch was more eagerly anticipated than the previous, creating a buzz Yamaha couldn’t compete against, despite its bigger factory.

Time as a Strategic Weapon

Speed alone doesn’t guarantee success. For example, chess grandmasters make more mistakes in speed chess (where moves must be made in a limited timeframe) than in traditional games. Faster moves therefore aren’t necessarily better moves. But what Honda unlocked was a far more powerful resource — they used time as “a strategic weapon [that was the] equivalent of money, productivity, quality, even innovation10”.

Honda excelled at turning data into action by continually experimenting with a variety of ideas, learning more quickly — through effective feedback loops — what the market wanted (or didn’t, making failure a learning opportunity) and launching new iterations before Yamaha even had time to respond to the previous one. Honda wasn’t playing speed chess — they were rewriting the rules of the game, making several moves to each one of Yamaha’s. In such a lopsided game, even an average player can defeat a grandmaster.

Honda and Fujifilm acted in ways consistent with Pal’chinskii’s principles. While it’s unlikely either of these Japanese firms were directly influenced by the young Russian engineer, their unorthodox moves drew on a shared foundation — the Eastern approach to strategy — a powerful way of creating a competitive advantage in uncertain times. We will explore this more deeply in the next chapter.

3 Time—The Next Source of Competitive Advantage. by George Stalk, Jr. HBR JULY 1988 ISSUE

4 Richards, Chet. Certain to Win: The Strategy of John Boyd, Applied to Business. Kindle Edition. Location 349

5 Competing Against Time. How Time-based Competition is Reshaping Global Markets. Stalk and Hout (1990) p136

6 Competing Against Time. How Time-based Competition is Reshaping Global Markets. Stalk and Hout (1990) p136-7

7 Competing Against Time. How Time-based Competition is Reshaping Global Markets. Stalk and Hout (1990) p137

10 Competing Against Time. How Time-based Competition is Reshaping Global Markets. Stalk and Hout (1990) p92