Sanctions have forced Russians to build things themselves, rather than buying from abroad. Fortunately, Russia possesses deep wells of creativity and ingenuity. Even the Economist Intelligence Unit once admitted that, “it’s a defensible statement that Russian human resources are the best in the world1”.

Historically, Russians have pioneered many technologies that are usually attributed to the West: steam engines (Cherapanov vs. Watt), lightbulbs (Lodygin vs. Edison), radio (Popov vs. Marconi), transistors (Losev vs. Bell labs), lasers (Basov and Prokhorov vs. Maiman), and even computers (Lebedev over Babbage or Turing).

In his book, Lonely Ideas, MIT professor Loren Graham acknowledges that Russians, “have legitimate claims to being pioneers in the development of all these technologies”. But he also raised two critical questions: When was the last time you bought something ‘Made In Russia?’ Where are all the Russian commercial powerhouses in these industries that Russians were pioneers in?

Communism may explain why Russia didn’t develop thriving commercial industries in the recent past. But the question today is: will it be different this time? Russians invented the first covid vaccine (Sputnik V), have made breakthroughs in mRNA vaccines for cancer, developed hydrogen powered vessels (Ecobalt) and space microscopes (SMM-2000S). Will these breakthroughs translate into lasting economic benefits, or will Russia be outcompeted globally again?

Russia excels at breakthrough inventions, but struggles to capture their economic value. In other words, it struggles with the type of innovation that transforms industries, which requires expertise in commercialisation, not just invention. Russia boasts Europe’s equivalents of Google, Facebook and Amazon (Yandex, VK, and Wildberries), suggesting there is serious commercial expertise in the country — but these are arguably exceptions, not the rule.

The question is: Which factors prevent Russian inventions from become global innovations?

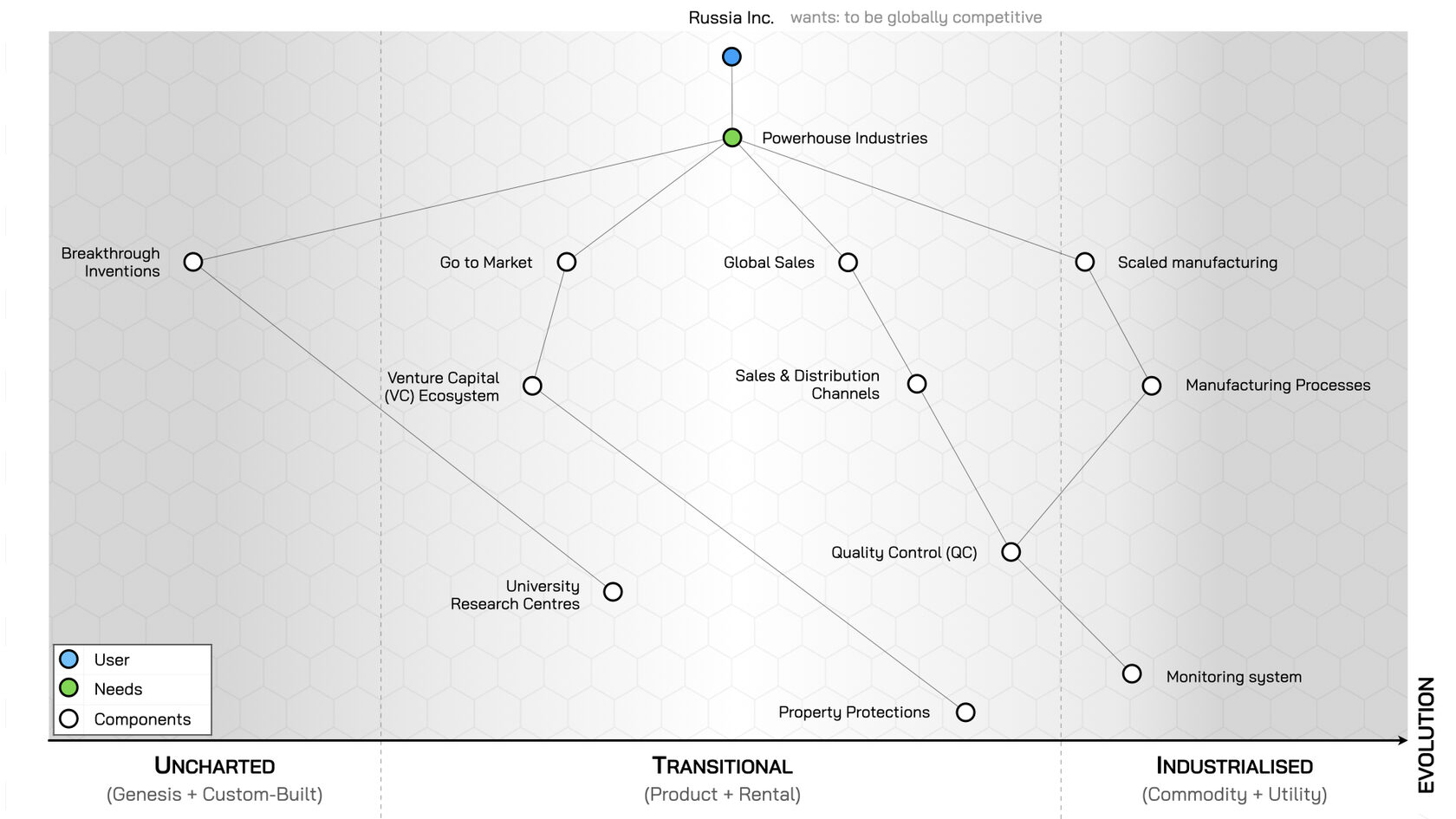

To explore this, we’ll use a Wardley Map — an open source tool for visualising a business landscape and identifying better strategic moves. If you’re unfamiliar with Wardley Maps, you can learn more here.

Ready to dive in? Let’s map out the steps in Russia’s journey from invention to innovation and try to identify what’s missing.

Mapping the Journey from Invention to Innovation

The focus of this map is ‘Russia Inc.’ — the Russian technical and commercial ecosystem — that needs to build ‘powerhouse industries’ in order to be competitive globally.

We’re going to show how to do that.

First. Russia Inc. needs the kind of breakthrough inventions that it excels in. Breakthroughs provide a unique advantage that can be capitalised on — such as Henry Ford’s moving assembly line, which powered the rise of Ford and the US automobile industry; or Apple’s iPhone, which launched the smartphone revolution and accelerated the dominance of Silicon Valley. Therefore, we place ‘breakthrough inventions’ (1) in the ‘uncharted’ space on our map as these are exciting activities that are new to the world and could become a potential source of future value — but are currently shrouded in uncertainty.

Research centres, often linked to universities, are essential to these breakthroughs. Therefore, we’ve placed ‘universities and research centres’ (2) in the ‘transitional’ stage on our map as there is more certainty about these, although they vary in effectiveness.

However, unless new inventions become innovations that capture economic value, they risk becoming more ‘lonely ideas’ that go nowhere. Therefore, Russia Inc. needs to refine how it ‘goes to market’ (3) to capture value from its breakthroughs. This is not the wheel house of universities and research centres so something else is needed.

Learning from the experiences of others suggests that a vibrant ‘venture capital (VC) ecosystem’ (4) needs to be developed: with business people who can recognise the commercial potential of a new breakthrough and can even ‘put their money where their mouth is’, providing the capital and know-how needed to take breakthroughs out of the laboratory and into the market-place. Developing such a vibrant VC ecosystem needs many things — and we could map this out in a detailed sub-map — but to keep everything high-level for now, we’re going to put just one component it needs — strong ‘property protections’ (5) to assure investors they will reap returns from any investments they make.

Once a breakthrough has proven viable domestically, the next step is to make ‘global sales’ (6) if we are to have any intentions of creating an industrial global powerhouse. This demands effective ‘sales and distribution channels’ (7) to get products to international markets, alongside rigorous ‘quality control (QC)’ (8) to ensure they meet their standards. Therefore, some kind of ‘monitoring standard’ (9) is also needed to raise the perception of goods in international eyes. For example, ‘Made in China’ used to be synonymous with cheap, inferior goods, but a clear strategy to move up the value chain and produce high quality technology is changing this perception — the same way Japan did half a century ago.

Finally, ‘scaled manufacturing’ (10) is critical for meeting the international demand the previous steps have created. This requires effective ‘manufacturing processes’ (11), which will need to be integrated with the ‘quality control’ and effective ‘monitoring’ systems discussed above.

Of course, many other activities will need to be performed, but this is a high-level map outlining the key components Russia Inc. needs to execute to turn breakthrough inventions into value-creating innovations that build global powerhouse industries. And the value of a Wardley Map is that we can make these assumptions visible so others can challenge us; telling us what's missing, wrong, or just not clear. The reason this matters is that turning inventions into innovations is beyond the capability of a single person — it needs an entire ecosystem, and now we have a way to discuss that and learn from each other about the next steps we should take.

In part 2 of this series, we’ll explore where ‘Russia Inc.’ is falling short today and what it needs to change to overcome these obstacles.

1 Human resources in Russia: The greatest opportunity, the greatest challenge. Economist Intelligence Unit (2007)