Previously, we looked at how to turn inventions (something new to the world) into innovation — the art of extracting value from the new. We also questioned why Russia Inc., with its long history of breakthrough inventions, fails to build global powerhouses on top of such inventions. In part two, we’ll start to answer these questions by exploring the challenges in turning breakthrough inventions into successful innovations.

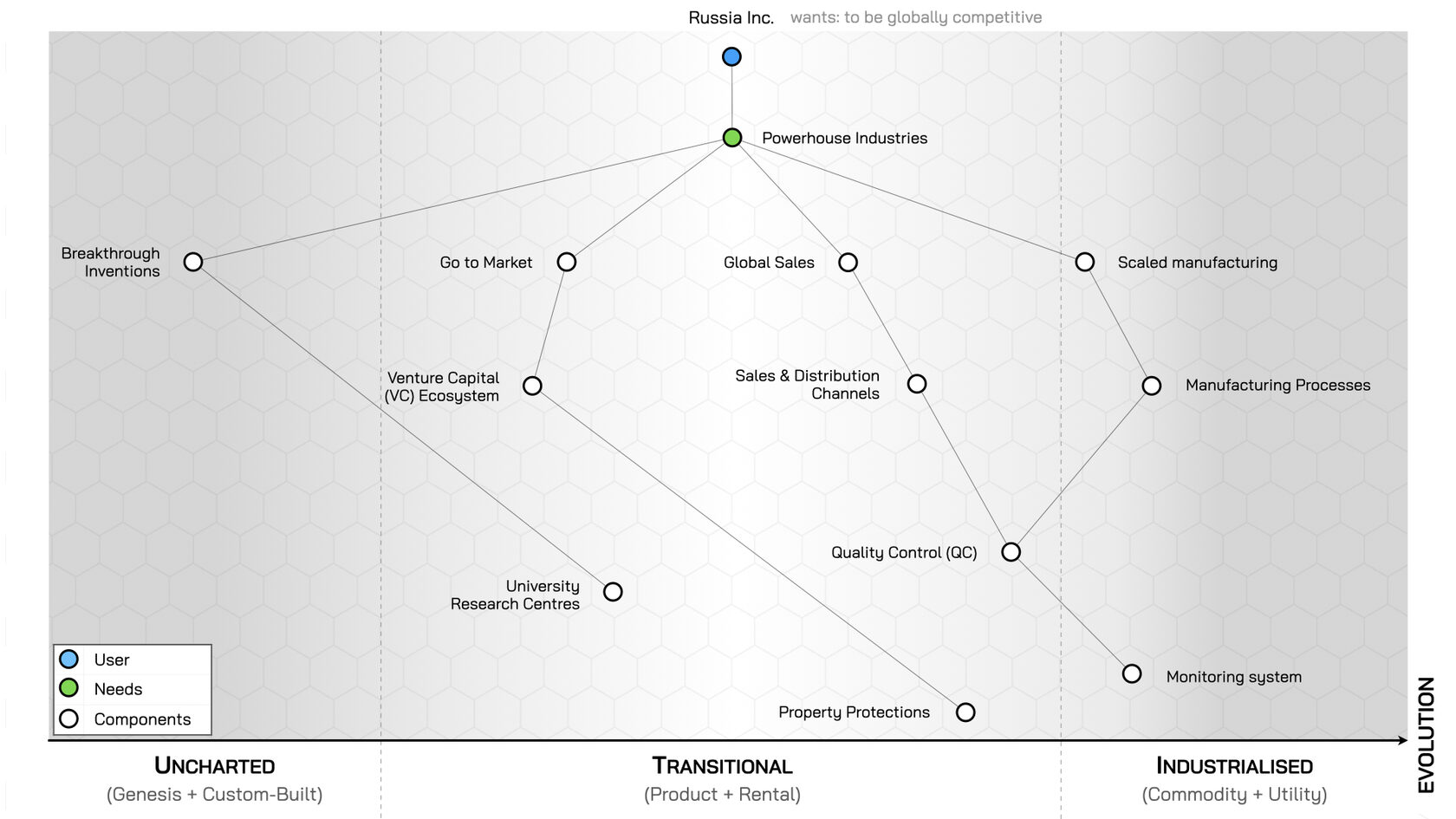

We start with a map, as this makes the discussion easier to follow. For this we use a Wardley Map — one of the most significant shifts in organisational thinking since Agile — to see what’s really happening, anticipate how the situation is changing and identify where the emerging opportunities and threats are.

(If you’re unfamiliar with Wardley Maps, you can learn more here.)

In part one, we created and explained the Wardley Map below — how ‘breakthrough inventions’ on the left-hand side of the map get turned into value-creating innovation through a series of complementary activities (‘going to market’ — ‘global sales’ — ‘scaled manufacturing’).

Turning Inventions Into Innovation

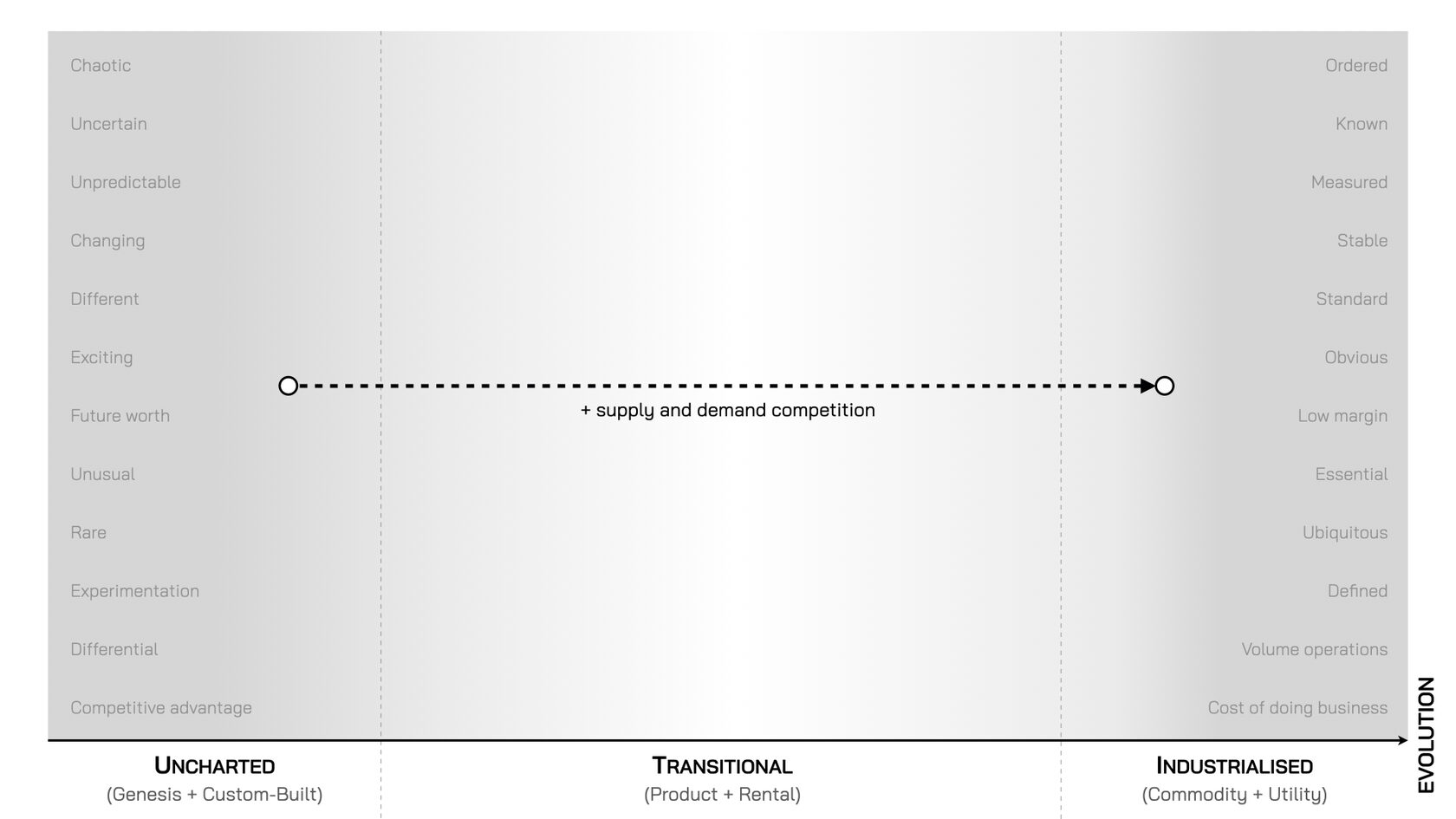

Anything on the left-hand side of the map, in the uncharted space, are the rare and unusual activities usually associated with new inventions. These are often breakthroughs that have the potential to become a source of future worth, but they require experimentation. This is the space of pure science which, the long history of Russian inventions suggests, is an area of strength for Russia Inc. — mainly due to its high-quality universities, research centres and an education system that develops the technical talent needed for frontier research.

Conversely, anything on the right-hand side of the map, in the industrialised space, is the exact opposite. This is where the low margin activities are, which require volume operations to create value. These are often costs of doing business today — think about computers, which 70+ years ago would have been on the left-hand side of the map as they were unpredictable but exciting, but today are ubiquitous and essential for business.

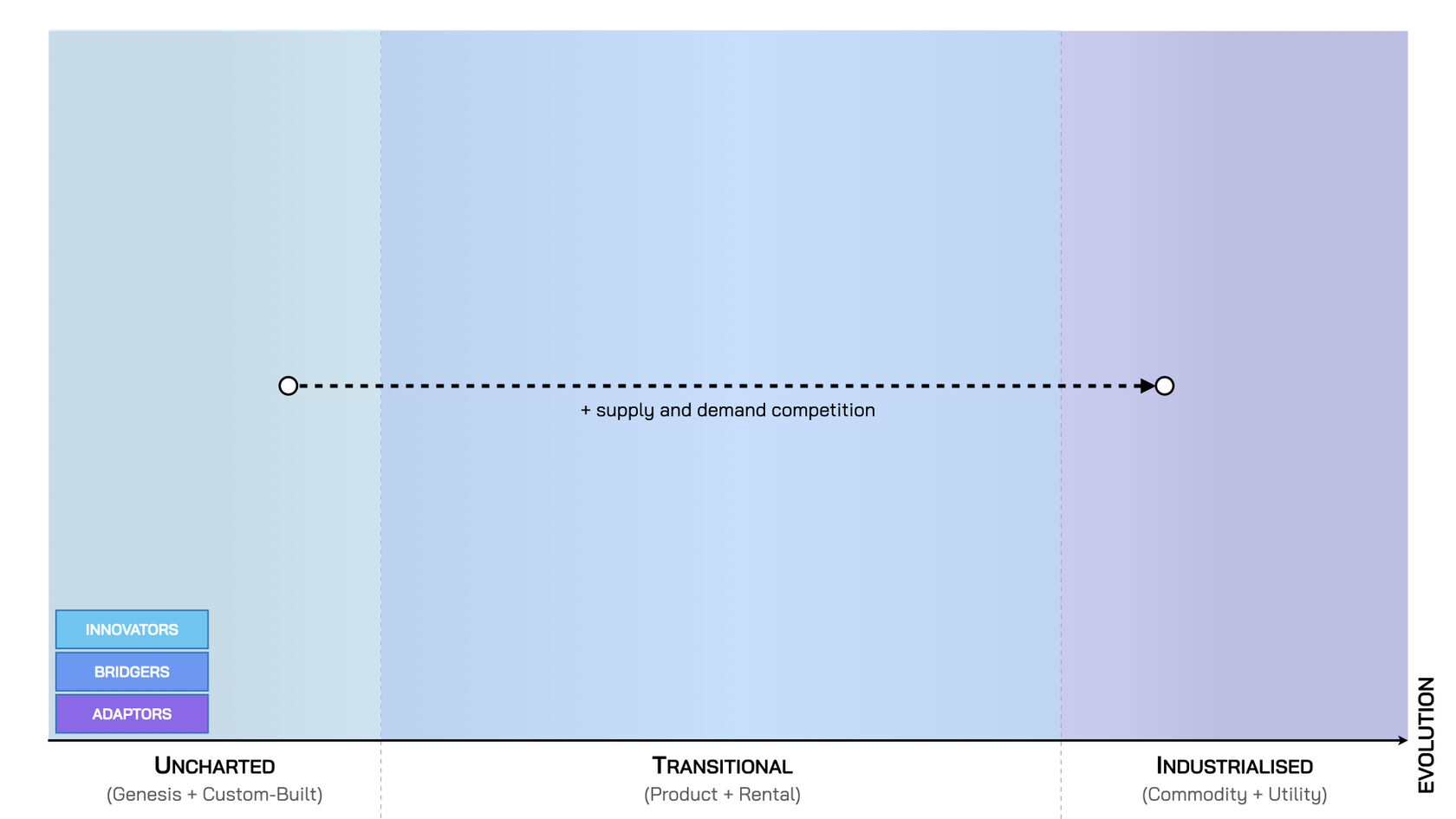

The maps below shows how everything is moving from left to right, driven by supply and demand competition. This means that, where there is demand, supply will rise up to meet it. And it’s this that creates value for users, by supplying them what they need (e.g. better computers) and for the organisation in the form of revenue.

Change Comes From Supply & Demand Competition

However, these two extremes are exact opposites and this gives rise to the ‘Innovation Paradox’ (Salaman and Storey, 20022). It is this paradox that Russia Inc. needs to overcome today if it wants to turn its long list of breakthrough inventions into value-creating innovations and develop global industrial powerhouses.

Put simply, the ‘innovation paradox’ states that, to innovate, an organisation must disrupt the established ways of doing things. But, while most leaders would agree that innovation is critical for their organisation’s survival and competitiveness, they focus most of their efforts on simply doing ’the current thing’ better: optimising for stability by implementing ‘best practices’ in an attempt to eradicate failure from their operations. This is the right approach for anything on the right-hand side of the map — such as core client services, or internal payroll systems — as failure here could cripple a business. But this focus kills their ability to innovate.

Innovation requires discovery and the development of new approaches that disrupt the status quo. But this can cause conflict inside the organisation. Those tasked with creating ‘the business of tomorrow’ are often seen as risky and dangerous by those running ‘the business of today’; while those creating ‘tomorrow’s business’ view those focused only on ’today’s business’ as stubborn and unimaginative. This is why bi-modal theories of organisational design fail to work in practice, as battles break out between the two, forcing leaders choose a side: Should they sacrifice the certain profits of today for potentially larger, but uncertain profits of tomorrow? Unsurprisingly, leaders tend to choose the certain profits of today (as their annual bonuses are tied to them). As a result, innovation suffers, and the organisation fails to adapt to a changing world.

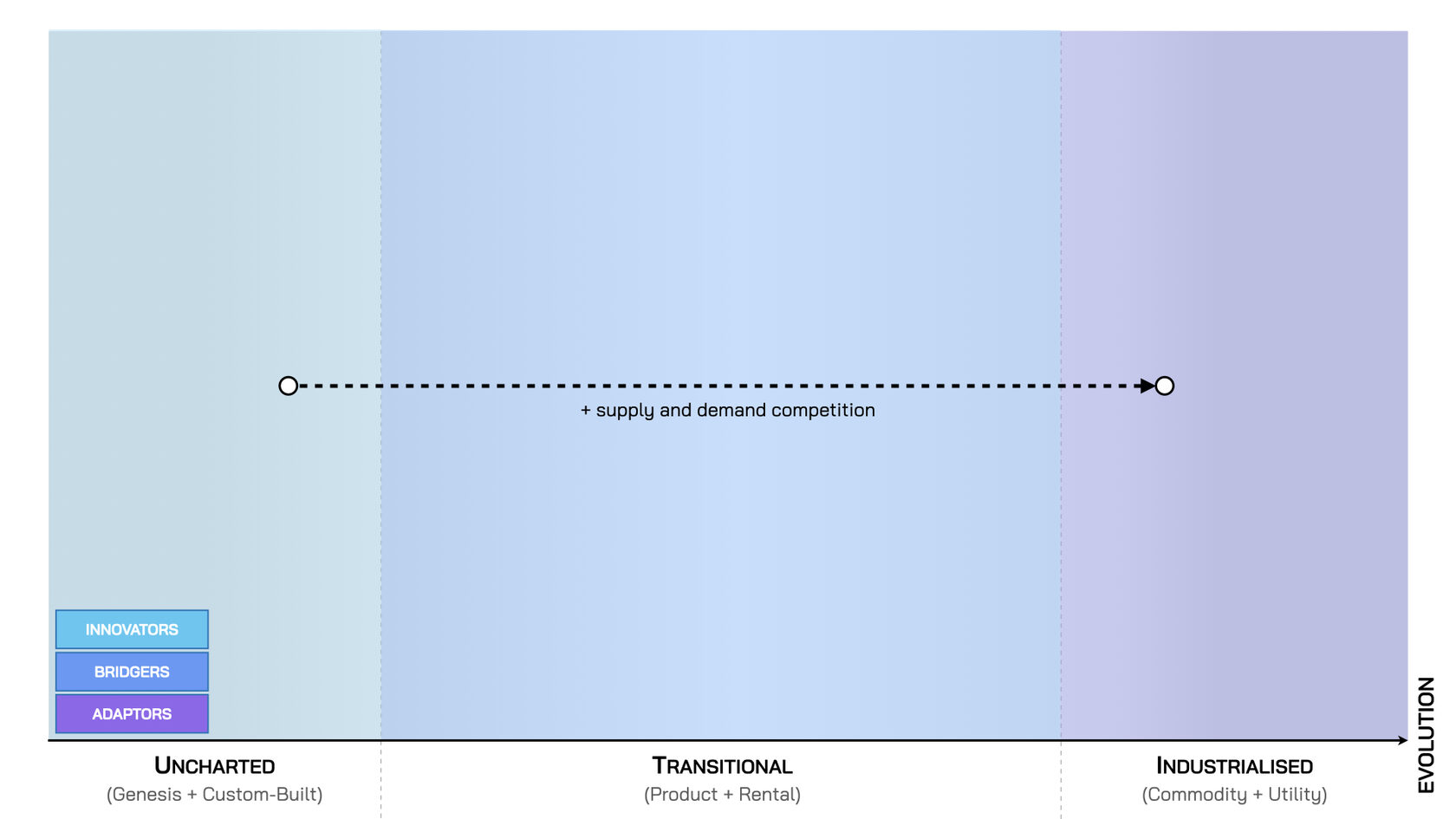

The challenge therefore is how to become an ambidextrous organisation: one capable of exploring new opportunities without sacrificing value today. This requires the addition of the ‘missing link’ between these two extremes — people who can bridge the gap between those focused on the business of today and those focused on the business of tomorrow. Unfortunately, few organisations know how to do this because they lack maps and can’t it (see image below). Unless they’re forced to innovate (e.g. sanctions) they abandon their risky innovation efforts, triggering an exodus of those focuses on the business of tomorrow, which, weakens the organisation’s ability to innovate in future.

In today’s rapidly changing world, this is not a good strategic move.

The Missing Link (The Three Types of People Needed)

What Russia Inc. needs to do to overcome the ‘innovation paradox’. This is the topic of part 3 in this series. We’ll explore how deploying appropriate methods and putting the right people in the right place — which means focusing not only on people’s aptitudes (i.e. their skill sets) but their attitudes as well (how comfortable they are dealing with uncertainty) — can deliver success. This can help Russia Inc. to start turning breakthrough inventions into innovations that create real value and that help them build global industrial powerhouses.

1 ‘Managers' Theories About the Process of Innovation’ by Salaman and Storey an article in the Journal of Management Studies (March 2002)