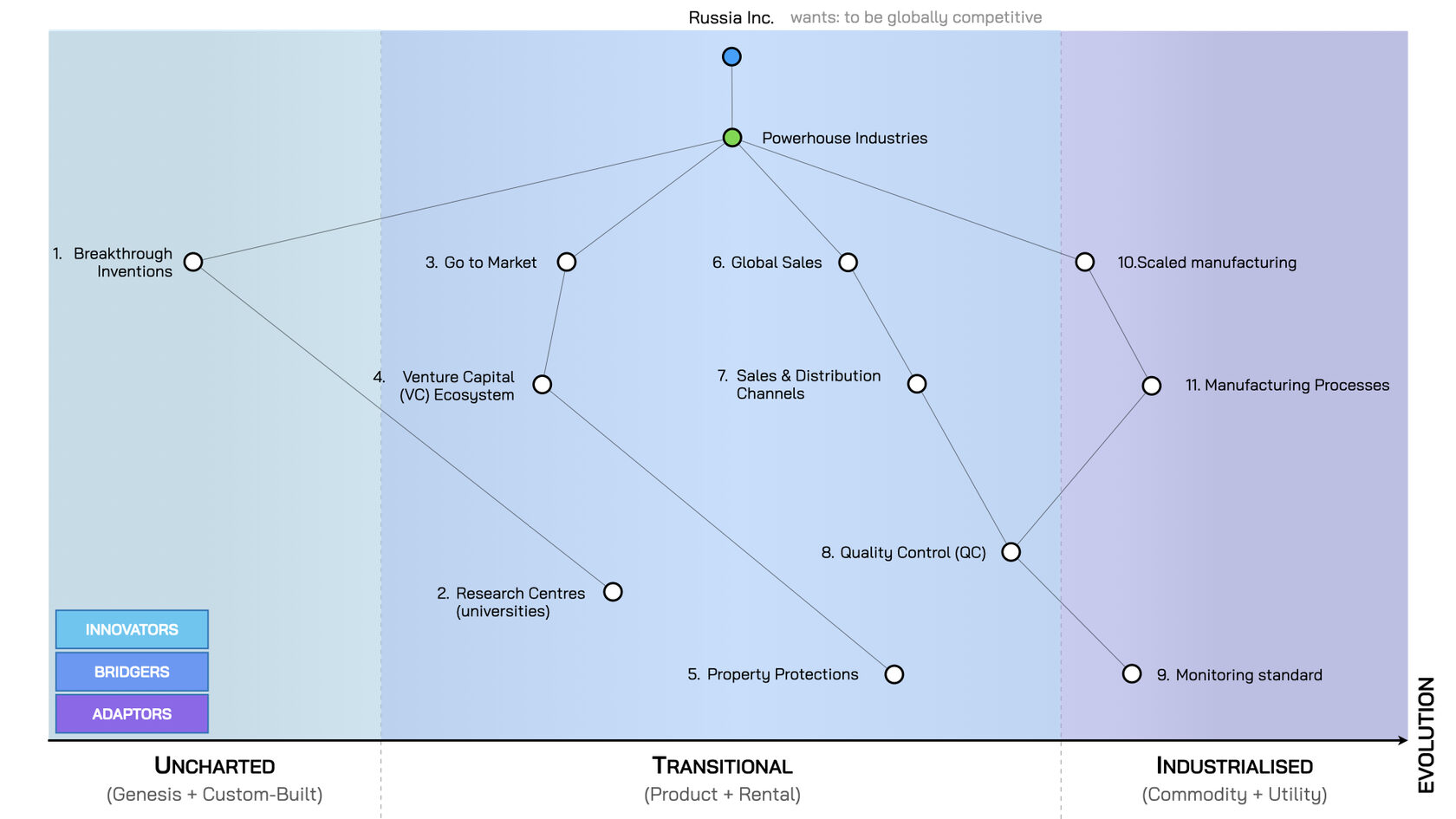

In part one, we asked why Russia Inc., with its long history of breakthrough inventions, struggles to build global industrial powerhouses. In part two, we identified the ‘missing link’ preventing organisations from turning inventions into innovation, (extracting value from the new). In this final part, we explore how to bridge that gap and what leaders must do to create dominant organisations, both domestically and globally.

To explore this challenge, we use Wardley Mapping — one of the most significant shifts in organisational thinking since Agile. This helps us see what’s happening more clearly, anticipate future changes, and make better strategic moves. (If you’re unfamiliar with Wardley Maps, you can learn more here.) If you’re comfortable with mapping, let’s dive in and explore how Russia Inc. (organisations in Russia) can solve one of its biggest challenges — how to turn breakthrough inventions into innovations that take the global market by storm.

In part one, we created a high-level map showing the steps needed to take new inventions to market and scale them globally. In part two, we identified the different attitudes of people required for success:‘innovators’ on the left of the map, who experiment and make breakthrough inventions; ‘adaptors’ on the right of the map, responsible for scaling operations into global markets; and the crucial ‘missing link’ between them — ‘bridgers’ who connect the two and turn the uncertainty of the new into something widely-adopted.

Many Russian organisations have two of these types of attitude in place, but very few have all three. It is this that holds Russia Inc. back from global success. However, this is something that can be quickly corrected.

Three Types of ‘Attitude’ Needed to Transition Breakthrough Inventions into Global Success

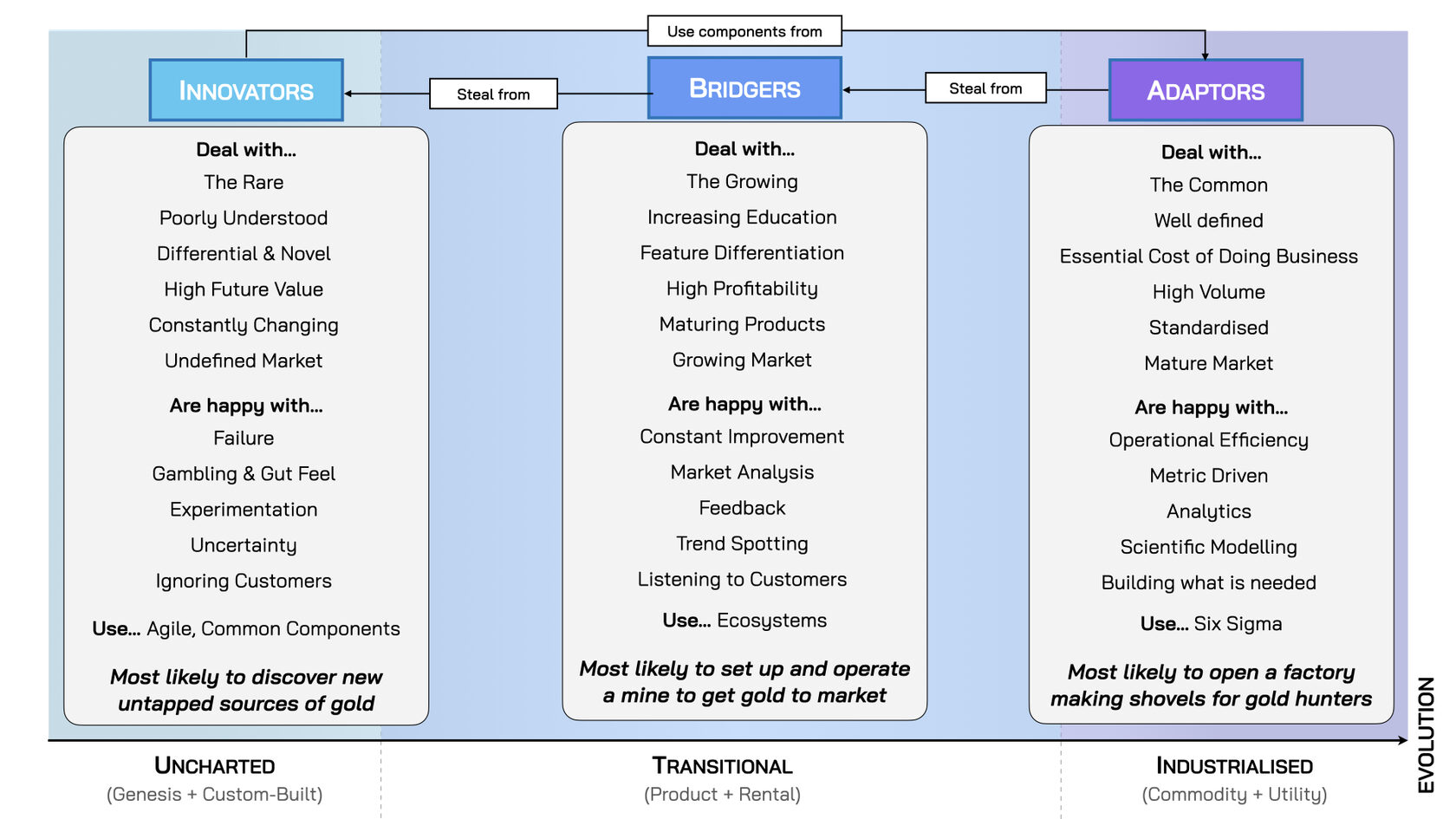

Organisations today hire based on ‘aptitudes’ — skill sets like finance, sales, or operations. But it’s equally crucial to hire for ‘attitude’. Dr Michael Kirton, a British industrial psychologist, studied problem-solving preferences and suggested that all people are located along a spectrum. At one end are ‘creative innovators’ — like Nikolai Tesla or Steve Jobs — who thrive on novel, radical, and spontaneous ideas. At the other end of the spectrum are ‘creative adaptors’ — like Thomas Edison or Tim Cook — who excel with the tried-and-tested, who manage risk well, and provide control.

However, these are outliers, as most people are in the middle of this spectrum — these are the ‘bridgers’ who bring out the best in the ‘innovators’ and ‘adaptors’. This was a message highlighted by Robert X. Cringely in his influential book, ‘Accidental Empires’ (1992) charting the rise of Silicon Valley. He popularised the metaphor of ‘commandos’ (innovators who establish a new beachhead), who are then followed in by the ‘infantry’ (to reinforce the initial success), and finally, by the ‘police’ (who ensure stability). This tri-modal approach is central to the Wardley Mapping method and has been successfully used by companies like AirBnB who enter new markets faster than rivals by ensuring they have the right attitudes for the challenge.

The Three Types of Attitude Every Organisation Needs

In this organisational model, ‘innovators’ are small teams with a variety of aptitudes (IT, marketing and operations people) who explore new possibilities in the uncharted space on the left of a map. However, to make sure they don’t get too attached to their ideas, organisations need to implement a ‘mechanism of theft’. This means that larger teams of ‘bridgers’ (also with a variety of different aptitudes) are encouraged to ‘steal’ the prototypes of ‘innovators’ and either commercialise or discard them — keeping ‘innovators’ focused on the new. ‘Bridgers’ then get close to customers, adjusting and improving these new products or services to maximise commercial revenues.

Eventually, all products or services become commoditised. This starts to happen when customers question the value for money they’re receiving. And this is where the largest team — the ‘adaptors’— step in. They ‘steal’ the commoditised product or service from the ‘bridgers’ and turn it into a utility-like service, so users only pay for what they use. Organisations that do this first enjoy a monopoly-like position, making it difficult for those playing catch up to differentiate their alternative with new features or branding (for example, you wouldn’t pay for your electricity because it had an Apple logo on it, would you?). Amazon Web Services (AWS) did this by turning a commoditised product (computer servers) into a pay-as-you-go utility-like service (cloud computing) that dominates the global market today.

These new, reliable, efficient utility-like services then become the platforms that ‘innovators’ experiment on. For example, ‘adaptors’ have provided Large Language Models (LLMs) as platforms that ‘innovators’ are experimenting on to create new ways of working. Therefore, we should expect a flood of new products and practices soon that will, in time, be commercialised by ‘bridgers’. Eventually, those new activities and practices will become the platforms on which the future of work will be built.

Organisations that get these three parts of the equation right today will become the global industrial powerhouses of tomorrow.

Creating the Conditions for Turning Inventions into Innovations and Discovering New Inventions Again

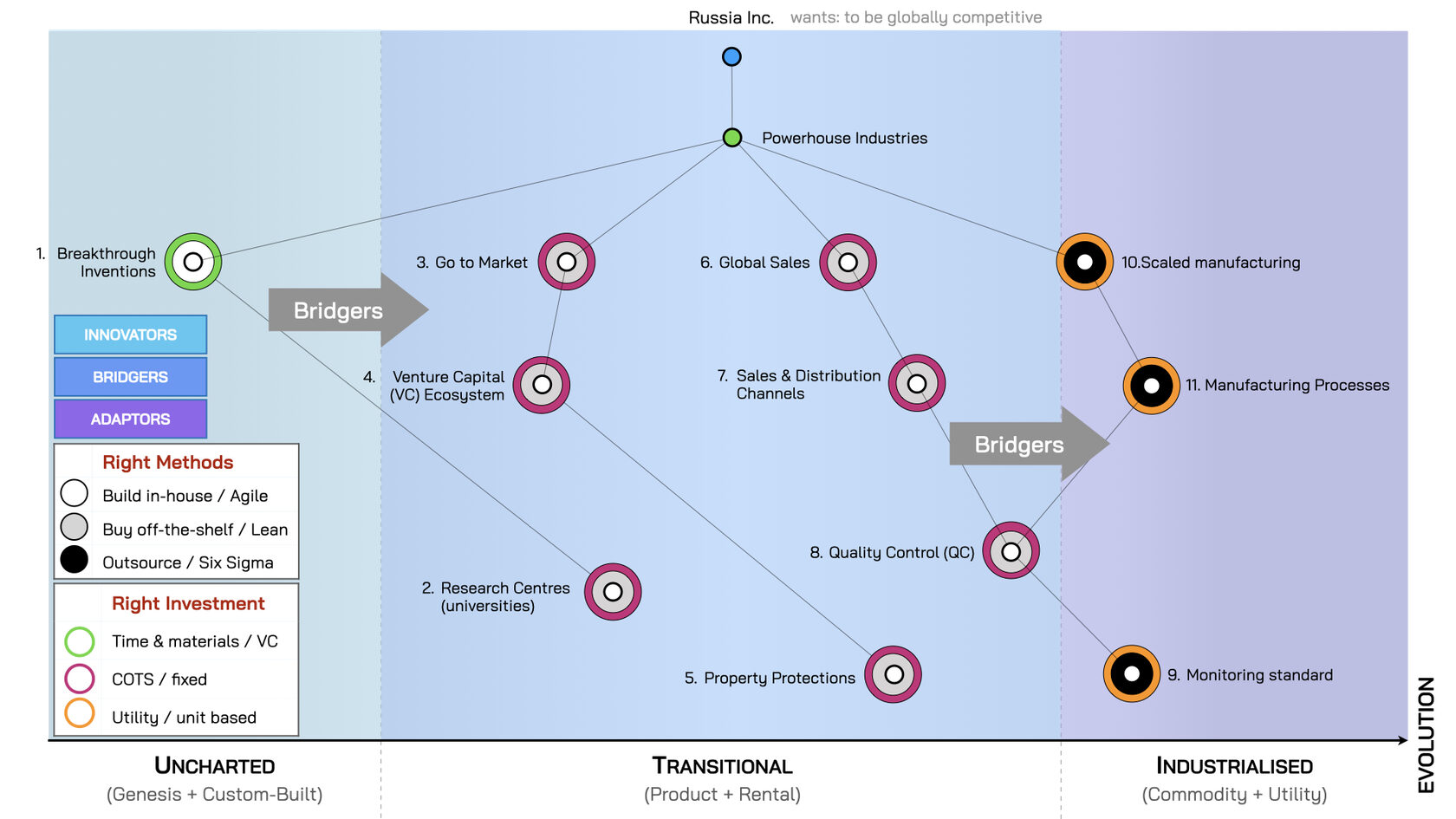

Adopting such an organisational structure can help Russia Inc. turn inventions into innovations and start dominating global markets. It requires hiring talent for attitude (not just aptitude) and putting them in the right places. With a map, we can understand where to put the right people, but also the right methods they need to succeed. ‘Innovators’ tasked to build the new themselves will use Agile-like methods, as these are excellent for reducing the cost of change that comes with experimenting. Leaders will support them by paying for time and materials, or take a venture capital approach to support their work.

Yet, ‘bridgers’ and ‘adaptors’ will need very different approaches, as their challenges are different. Leaders must avoid the mistake of thinking what worked in one part of the map will work everywhere. ‘Bridgers’ need to use Lean-like methods to increase the margins of products or services by reducing waste, or buying any necessary sub-components commercially, off-the-shelf. While ‘Adaptors’ should use Six Sigma-like methods to scale up, as this approach is great for reducing deviations and service outages. Alternatively, they can outsource sub-components to providers and only pay for what they use (e.g. the cloud).

Once this structure has been established, leaders only need to manage the hand overs — the ‘mechanism of theft’ — between teams, smoothing out conflicts at the team leader level. Once up and running, this system takes care of itself — with each team focusing on their own challenges, while the ‘mechanism of theft’ ensures that breakthrough inventions are pulled through and commercialised on the market, before being scaled up.

This is how Russia Inc. can address one of the biggest problems holding it back for over a century — effective coordination between different collectives in a system, whether this is within an organisation, or in different parts of an economy, like universities and commercial companies. This will help Russia Inc. — in the words of the most famous Russian that most Russians have never heard of — tap into its most valuable “non-utilised force [one that] will bring more fruits than anything else”— its deep reserves of talent — in comparison to which, “all the other great natural riches of the country pale in significance”.

If you liked this series consider joining our telegram channel t.me/wardleymapping or sign up for future blog posts on our website https://powermaps.net/blog. Next time we’ll explore how Huawei successfully tapped into Russia’s deep well of talent capabilities to defeat the devastating sanctions that had been placed on it.