Climate changes a physical landscape. A river that can only be crossed by boat in summer may freeze in winter, making it possible to cross on foot then, in spring, when the snow melts, the river can become a raging torrent, impassable to all. Similarly, the ‘economic rules of the game’ change a business Landscape, unfolding “according to a general pattern that can not only be anticipated, but can be manipulated to one's advantage1”.

Awareness of how Climate changes a Landscape therefore is key to seeking victory from the conditions.

Fig.97: The Strategy Cycle

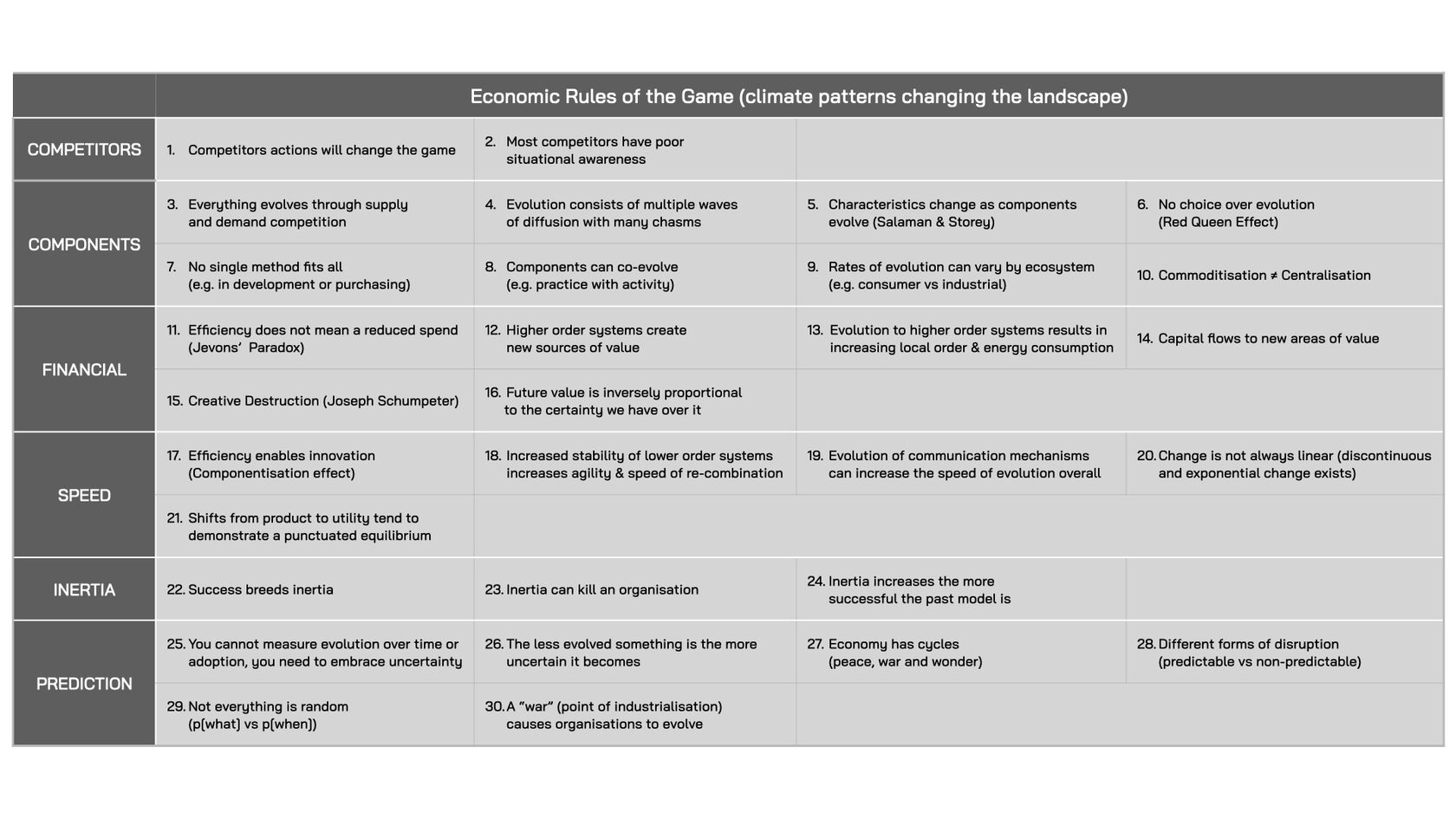

Carlota Perez’s work (see previous chapter) illustrates how economies evolve through recurring patterns of change. Understanding these patterns can help us better anticipate2 change so we adapt quicker — rather than responding belatedly to events after they’ve happened. Simon Wardley identified 30 recurring economic patterns, based on established economic models, which he called the ‘economic rules of the game’.

Fig.98: The 30 Economic Rules of the Game

Armed with a map of the Landscape, we can apply the economic rules to it to identify the potential in the situation — where the emerging opportunities and threats are, and what are our options for action. Sharing these assumptions allows others to challenge3 them helps develop collective knowledge. And, in a world of constant and rapid change, we either become a learning organisation or we get out-competed by one that is.

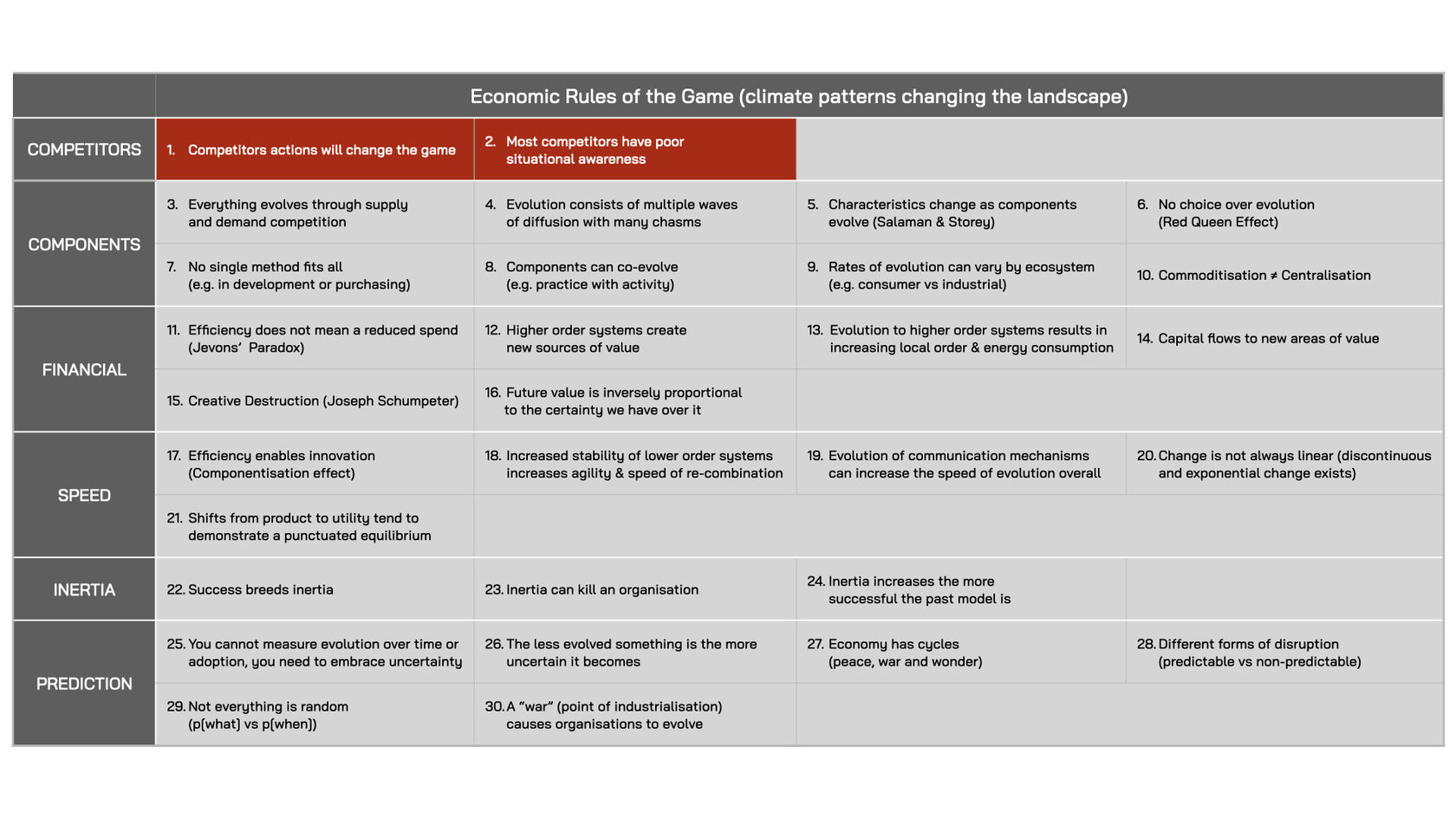

Let’s dive more deeply in the economic rules of the game, starting with the two rules concerning ‘competitors’.

Fig.99: Economic Rules of the Game: Competitors

Rule #1. Competitors Actions Will Change the Game

The moves competitors make can change the game dramatically. For example, Amazon launching cloud services or Apple releasing the iPhone didn’t just transform the computer and mobile phone industries, but also sparked the mobile revolution, which impacted almost every other industry. However, our ability to predict such changes is limited because we don’t know what’s going on behind the closed doors of our rivals4. To anticipate their next moves, some organisations attempt to think like their competitors — identifying recurring patterns in their past behaviour, supplemented with data gathered from social media, industry events or experts — to try and ‘war-game’ potential scenarios. Yet surprises continue to happen because we’re rarely dealing with the actions of a single competitor. Instead, we’re facing the combined effects of multiple competitor actions across the entire business Landscape, which can be unpredictable and bewildering.

For example, when ChatGPT was released in 2022, it quickly triggered the appearance of rival AI chatbots, changing user expectations about what these tools can do and how they can be used. At the time of writing, we’re still taking the first tentative steps on a long journey that will likely lead us down paths we have not yet imagined — except perhaps in the realm of science fiction — creating both opportunities and threats. We could be witnessing the ‘Big Bang’ of a new technological and financial revolution, as AI is already attracting capital and talent that will produce new products and services that will spread widely. This revolution — if it is one — has the potential to disrupt entire industries while launching new, previously unimaginable ones.

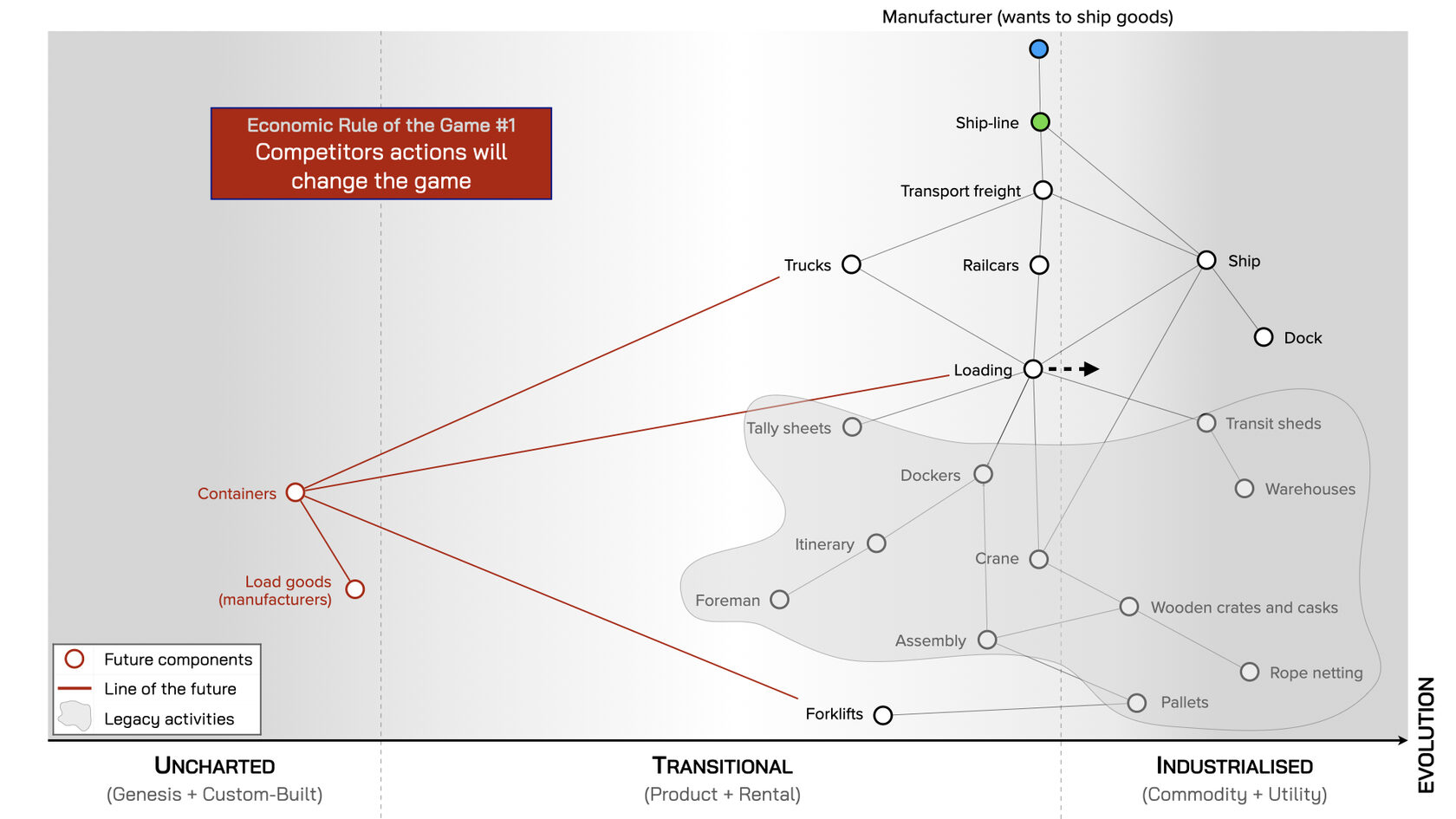

However, it’s not only a ‘Big Bang’ event that changes the game. Sometimes it can just be the actions of a single competitor that disrupts entire industries. Take the launch of Apple’s i-phone in 2007, which not only changed consumer expectations of what a smartphone should be, but also ushered in a new business model — revenues from its App Store and iTunes — that changed the industry’s perspective on how to monetise products5. Similarly, the launch of Malcolm McLean’s modern shipping container half a century earlier had a comparable effect. Containers, like smart phones, were not new. But McLean (like Jobs later) was able to clearly communicate the advantages of his product by inviting dignitaries to witness a demonstration of how containers radically reduced loading times. Like Jobs, McLean was able to back up his vision with enough capital of his own (derived from his successful businesses as a trucking magnate) until new capital flowed in, triggering a complete transformation of the entire transport industry — which had been McLean’s vision.6

Fig.100: Action Changed The Transport Industry

Rule #2. Most Competitors Have Poor Situational Awareness

When disruption hits a market it often goes unnoticed at first, because it begins at the margins and is easy to dismiss as niche. This happened in the computing industry around 2007. Around the same time that Apple’s iPhone was poised to disrupt industries, Amazon introduced AWS (Amazon Web Services), offering scalable, pay-as-you-go computing resources. AWS was developed to solve a problem Amazon itself faced in scaling its e-commerce business — the cost of building infrastructure across multiple locations to handle peak traffic, which frequently sat idle. But, solving this problem for itself, Amazon knew it would be solving a problem for many other businesses as well. They were right, as AWS now has revenues in excess of $100 billion per year.

However, in the early days of cloud computing, there was significant uncertainty about it: organisations were unsure what it was, how it could be used or, most importantly, whether it was worth adopting or not. Busy with the rest of the business, some leaders outsourced their thinking about these issues to management consultants. Yet, by as late as 2009, McKinsey were still writing that there was a lot of “irrational exuberance and unrealistic expectations" surrounding cloud computing, stating that ‘the buzz was disconnected from reality as the promised cost savings just weren’t there.7 McKinsey was spectacularly wrong about the cloud, and the organisations that relied on their advice suffered as a result. So, why do leaders do this?

Fig.101: Cloud Computing OverHyped

Overwhelmed with competing priorities, leaders rely on others to assess the potential in peripheral matters. However, when leaders fail to identify emerging changes of substance, or develop appropriate responses to them ahead of time8, they demonstrate a lack of situational awareness9. In other words, they fail to understand their environment, anticipate how it might change or identify where better options for action are.

The concept of situational awareness was ‘re-discovered’ in the twentieth century and spread in military circles, due to the work of Colonel John Boyd, a fighter pilot instructor. His work was informed by the Korean War, when the US Air Force was shooting down its counterparts at a ratio of 10:1, despite flying the F-86 which was a technically inferior aircraft to the Soviet-made MiG-15 flown by rivals. Initially, the US Air Force attributed their success to pilot training, but later admitted that, “even when we got our hands on MiGs later on, and flew them with our own pilots, the F-86 still won more than it should”. The “secret”, it turned out, was that “the F-86 had a bubble canopy, allowing its pilot much better observation of the fight and full power hydraulic controls, which is like power steering for fighters”. This meant that while, “the MiG could, in certain circumstances, turn tighter than the F-86, its heavier controls meant that by the time the MiG pilot had his airplane doing one thing, the F-86 was already doing something else”.10 In this highly-dynamic environment, being able to see and react a split second faster than rivals provided a critical advantage. And Boyd would later argue that the principles of awareness and effortless action would provide an advantage in any competitive situation.

Yet, in the world of business, few players have developed a sophisticated level of situational awareness. This is because most organisations focus excessively on building internal capabilities (in line with the western approach to strategy11) and spend little time observing their external environment. Those few that attempt to do so quickly become overwhelmed by the complexity of the market, as competitor actions change the game in unexpected ways (see rule #1 above). This uncertainty encourages leaders to turn to technology to help them ‘cut through the complexity’ and make better decisions in a changing world, but this makes them dependent on tools they neither fully understand nor know how to challenge effectively.

A growing concern in organisations today is ‘automation bias’ — a tendency to unquestioningly trust automated decision-making systems, even when contradictory information arises. This bias is evident in everyday scenarios, such as people driving cars into rivers while blindly following their sat-nav, but is also becoming a threat to organisations, with decisions made based solely on the outputs of technology, with little thought to the biases embedded in the training data they were built on. For instance, the share price of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway used to go up every time the actress Anne Hathaway appeared in the news as the automated stock trading programs many companies use would pick up chatter about the latter and mistakenly apply it to the former (see fig.102).

Petr Pal’chinskii’s12 warning a hundred years ago about the danger in believing that ‘any solution that incorporated the latest technology was necessarily the best solution’ has never been more relevant.

Data is always from the past, which limits its usefulness as a guide to the future. The alternative is to develop awareness of what’s really happening now, how it’s changing and where the better options for action are. This speaks to using technology as a tool to aid decision-making, rather than replace it. This is why we apply the economic rules of the game to maps — to deepen our understanding of how a situation is evolving, so we can start shaping the Landscape to our advantage — rather than making plans based on data about the past. With that in mind, let’s explore some more economic rules of the game and see how we can use them to enhance our situational awareness and start out-thinking and out-moving our rivals.

Fig.102: Berkshire Hathaway, Not Anne Hathaway

1 Yuen, Derek M. C.. Deciphering Sun Tzu. p.53

2 “Anticipate” rather than “predict” change as prediction is something economists are notoriously bad at — most having predicted three of the last two recessions but never the next one.

3 For a reminder of the importance of challenging, see chapter sixteen — The Importance of Challenge.

4 Unless, of course, you have taken the works of Sun Tzu very seriously and have developed a network of spies, (which is illegal in the corporate world).

5 However, the iPhone should not be mistaken for a ‘disruptive innovation’ as originally defined by Clayton Christensen. Disruptive innovations are typically inferior products that, by being cheaper and ‘good enough’, attract niche market segments overlooked by competitors. Over time, these products improve and grow to outcompete more established rivals. The iPhone, by contrast, was not an inferior or low-cost product. Instead, it was an evolutionary step — a “better” phone that captured a significant market. While it disrupted (or upset) the mobile phone industry and impacted many others, it did so through improvement rather than by starting as a low-end alternative.

There is a much better case for labelling the iPhone as a ‘disruptive innovation’ (in Christensen’s meaning of the term) for the laptop computer market. Here was an inferior computer in terms of power, functionality and cost (initially), but found its market as it satisfied the needs users had for a computer that could fit into their pocket. As that practice spread, industries started to create products (apps) that enabled them to do things that required a more a bigger, bulkier laptop top or desktop computer to do. The iPhone then is arguably is the start of the mobile computing industry that disrupted the market for any device that wasn’t mobile.

7 https://www.businessinsider.com/mckinsey-cloud-computing-overhyped-still-too-expensive-2009-4?op=1

9 For a reminder of the importance of situational awareness see chapter eight — The Eastern Approach to Strategy.

10 Certain to Win: The Strategy of John Boyd, Applied to Business. Chet Richards.