Progress is commonly understood to unfold through the invention of a technological marvel that’s gradually adopted by the market, which then drives greater economic development. However, the work of economist Carlota Perez1 reveals that this journey is neither simple nor smooth, as “societies are profoundly shaken and shaped by each technological revolution and, in turn, the technological potential is shaped and steered as a result of intense social, political and ideological confrontations and compromises”.

Perez identified the sequence these turbulent journeys of progress take:

- Technological revolution

- Financial bubble

- Collapse

- Golden/gilded age

- Political unrest.

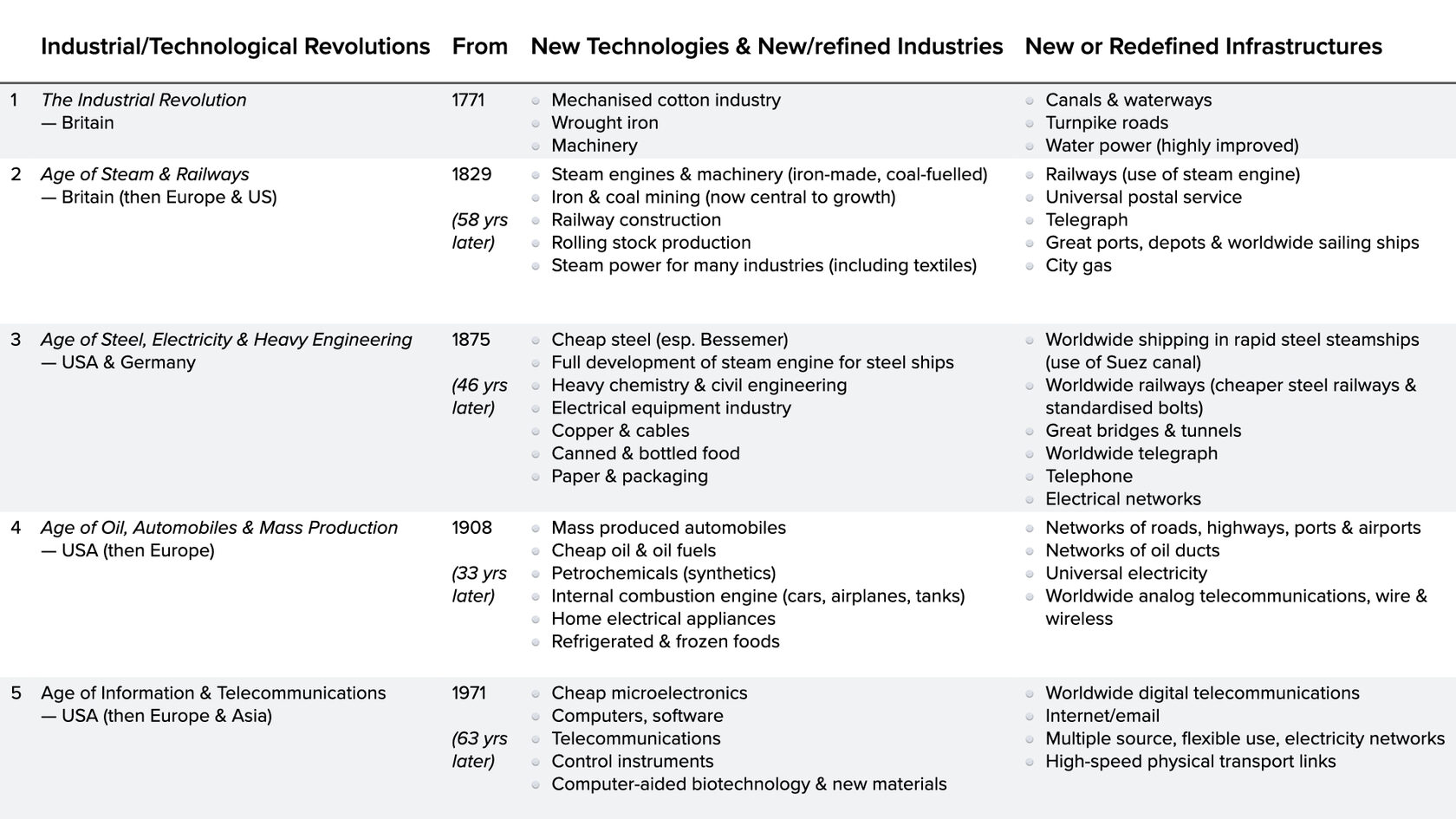

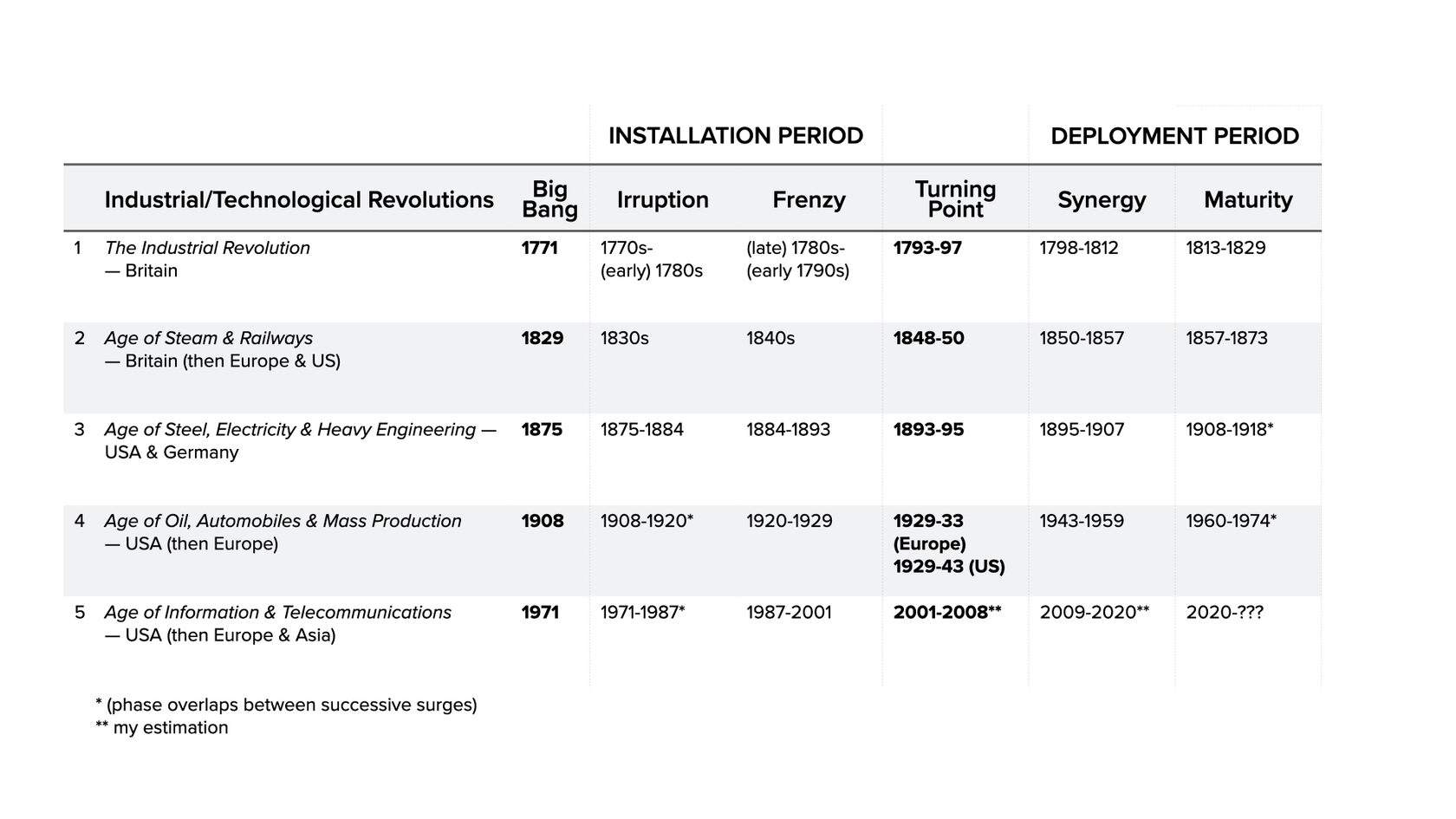

Perez explored five historical revolutions, showing how the emergence of multiple new technologies sparked significant economic and social change. The ‘Industrial Revolution’, which began in Britain in 1771 was triggered by new technologies like the ‘spinning jenny’ and the power loom, leading to the mechanisation of the cotton industry. Yet it was also advances in iron bar production (without the need for charcoal) that provided the advanced machinery needed to build the infrastructure — such as canals and waterways, turnpike and toll roads as well as highly-improved water power — the industry needed to develop further. These new opportunities, which attracted significant capital from investors seeking higher returns, combined to change the structure of the economy and eventually society. This sequence, Perez found, repeats across all five industrial and technological revolutions in the modern era.

Fig.94: The Five Industrial/Technological Revolutions (Perez)

However, as Perez pointed out, these were not smooth transformations from the ‘old and inferior’ to the ‘new and improved’. Technological revolutions tear apart the very fabric of economies and society — creating divides between new industries that flourish and old ones that decline; between firms that adapt to the new and those that don’t; between people whose skills are in demand and those whose knowledge has become obsolete; between regions that thrive by attracting firms of the future and those that stagnate; and between nations that ride the wave of innovation and those that get left behind, where social upheaval erupts as populations challenge the legitimacy of their failing leaders.

The Installation Period

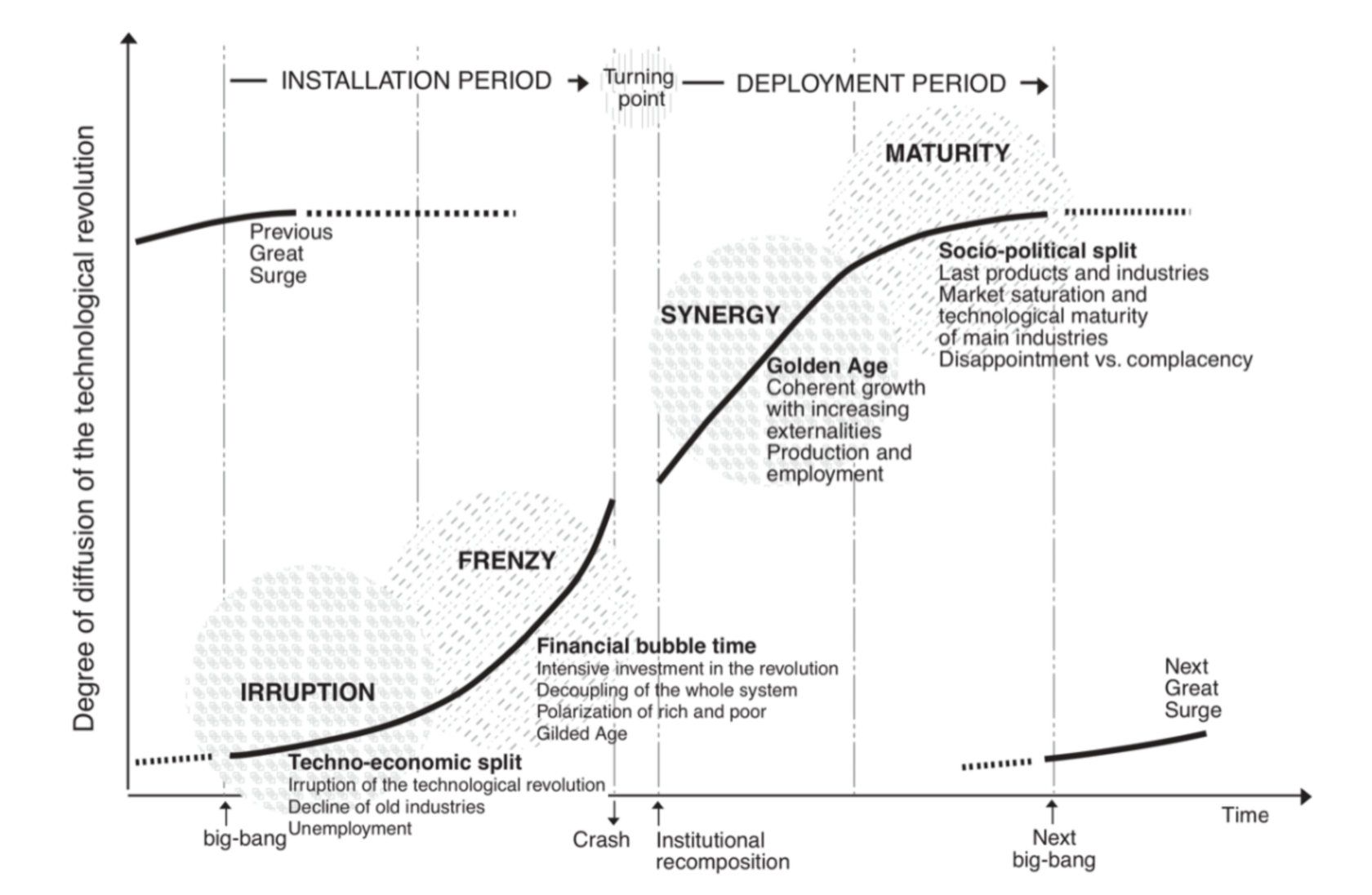

The sequence of economic and social change outlined by Perez starts with a ‘big bang’ — the ‘irruption’ of new technologies in a world then experiencing stagnation, such as the stagnation in the US during the 1970s, from which the Age of Information and Telecommunications emerged. Entrepreneurs are the first to embrace these new technologies, experimenting to explore their potential. Financial capital, seeking better returns on investment, soon follows to exploit that potential. The availability of capital attracts more entrepreneurs, who then compete by making better products to meet user needs more effectively. As the potential of the new technologies becomes clearer, even more new capital and talent flows in, diffusing them further.

At this time, the major players in established industries remain focused on extracting profits from their existing markets2, as executive bonuses are linked to these metrics. They justify their ‘strategic’ decisions by dismissing the new technologies as being as ‘niche’ as IBM did with personal computers in the 1970s and then later in the 2000s with cloud computing. However, the flow of customers from the old technologies (mainframes and servers) to the new (PCs and cloud) starts to turn from a trickle into a flood and the pressure on those “wedded to the old model and especially to the ideas and ideals of the established paradigm” grows. Eventually this will turn into “bewilderment [as] the world seems to be falling apart and the old behaviours and policies are impotent to save it3”.

A time of ‘frenzy’ follows. Financial investors, now accustomed to over-sized gains from the success of their earlier investments in this technological revolution, invest in more of the same (more canals, more railways, more dot.coms) or move into speculative assets like real estate, creating bubbles that suck in capital from the rest of the economy, starving it of investment, leading to shortages and price inflation. At this time “the general behaviour of the economy is increasingly geared to favouring the multiplication of financial capital, which moves further and further away from its role as supporter of real wealth creation.”4

The chasm between ‘Wall Street and Main Street’ now widens. New millionaires and billionaires are created faster than ever, while the majority get left behind, (as in the 1880s, the 1920s and 1990s). A blind eye gets turned to illegal practices and ever wider-spread corruption that’s justified as the legitimate pursuit of wealth. However, “the whole of the installation period could in a sense be understood as an exploratory time, when the engineers, the entrepreneurs, the consumers and the financiers test the various directions of development of the technological revolution, both in production and in the market. It is a huge trial and error process eventually to affect the whole of society5”. Eventually, the tensions and turbulence that have built up in this period lead to a major economic crash and a ‘turning point’ is reached.

Fig.95: The Installation and Deployment Periods of Technological and Financial Revolutions (Perez)

Turning Point

Tensions have been building between the winners of the ‘installation period’ and the majority who were left behind, but also between investors, who now have inflated expectations that entrepreneurs struggle to deliver on, as key resources, such as materials or talent, become scarce as demand outpaces capacity. Eventually, a point is reached where this economic and social trajectory can no longer continue and a change is needed — one that pays “greater attention to collective well being, usually through the regulatory intervention of the state and the active participation of other forms of civil society6” — a turning point.

This turning point is often a ‘violent and painful recomposition’ and rarely undertaken voluntarily or for altruistic reasons. It’s often triggered by pivotal events, such as the repeal of the Corn Laws in Britain in 1846, in response to economic distress and growing political agitation during the second technological revolution, or the ‘New Deal’ following the Great Depression triggered by the stock market crash of 1929 during the fourth technological revolution. A long, deep recession forces decision-makers to confront the unsustainable tensions that threaten to consume them all, much like in the revolutions that swept across Europe in 1848. “The turning point is then a space for social rethinking and reconsidering. It is an important crossroads for socio-institutional decision making. It is the time when the leading actors in the economy, society and government recognise the excesses as well as the unsustainability of recent practices and trends, however wonderful they may have seemed until then”.7

At the turning point, the ‘shape the world of the next for the next two or three decades’ is determined. This can lead to greater prosperity and achievement, as seen in Victorian England or post-World War II America, now considered ‘golden ages’. However, if investors are bailed out and not allowed to fail it makes it “highly improbable that financial capital will ever accept and abide by the necessary regulation8.” What follows is a ‘gilded age’ of continued economic growth, but only for the wealthy. The era of the ‘robber barons’ in the US, following the severe banking panic of 1893, exemplifies this ‘gilded age’ path, as the period following the global financial crisis in 2008 may come to be seen. This is a time of rampant corruption, where the masses experience continued hardship and lose trust in institutions, leading to widespread social unrest.

The Deployment Period

The ‘turning point’ occurs midway through a technological revolution, after massive capital inflows have helped build the essential infrastructure — new canals, railways, electricity networks, transport networks, digital telecommunications — the new technology needs to be fully installed in the economy. The new “paradigm has [now] triumphed and is ripe for widespread diffusion. By then, the main dynamic products have been identified and the dominant designs determined, their industries are structured and well connected with one another, the infrastructure is basically in place and the consumption patterns are pretty much defined9.”

The new revolution begins to ‘blossom’ as the focus shifts to getting “the thousand and one small details – sub-technologies, arrangements, architectures – to fall into place that adapt us to the new technologies and them to us.” This process takes time as it requires “overcoming the inertia of vested interests, long-held prejudices and dogmas, cultural views, practical routines and ingrained habits, especially when they had previously been successful10.” Cultural and institutional change takes even longer as it needs “powerful political pressures11” — which is why an economic crash and deep recession are often necessary to bring it about, as the crises loosen the shackles of inertia (resistance to the new) and usher in the ‘deployment period’.

Now is a time of ‘synergy’. There’s rising employment for the masses and greater social cohesion as a new middle class emerges with vested interests in the economy’s continued prosperity. “Fast and easy millionaires are rare, though investment and work lead to persistent accumulation of wealth. Production is the key word in this phase” and technology is increasingly seen as a ‘positive force’, as is finance since it directly supports production. “It is a time of promise, work and hope. For many, the future looks bright12”. Government plays a central role, providing an ‘adequate’ regulatory framework that supports the on-going technological revolution: legal frameworks that create a ‘safe and reliable’ environment for institutional investors to enter the market; a tax system that stimulates demand for the new; worker benefits to ensure salaries are sufficient to purchase the “masses of consumer durable goods” now being produced; and worker protections to ensure those goods don’t have “to be returned due to consumer default with each economic downturn13”.

The time of ‘synergy’ creates the conditions for the modernisation of every industry in the economy, marking the complete victory of the technological revolution. It has taken a series of “massive economic transformations [that] involve complex processes of social assimilation. They encompass radical changes in the patterns of production, organisation, management, communication, transportation and consumption, leading ultimately to a different ‘way of life’. Thus each surge requires massive amounts of effort, investment and learning, both individually and socially. That is probably why the whole process takes around half a century to unfold, involving more than one generation14.”

Fig.96: Installation and Deployment Periods of the Five Industrial/Technological Revolutions (Perez)

Eventually, each technological revolution reaches ‘maturity’. This is “the twilight of the golden age” — one that “shines with false splendour15”. Markets become saturated and the life cycle of new products grows shorter as the new (built with now widely understood technologies and practices) is quickly copied, making advantages from innovation fleeting. Financial capital becomes more conservative, investing in mergers and acquisitions, off-shoring expensive production and seeking new markets for old products to maintain previous profitability. “All the signs of prosperity and success are still around [and] those who reaped the full benefits of the ‘golden age’ (or of the gilded one) continue to hold on to their belief in the virtues of the system and to proclaim eternal and unstoppable progress …. But the unfulfilled promises had been piling up, while most people nurtured the expectation of personal and social advance. The result is an increasing socio-political split16.”

During the ‘maturity’ phase protests often break out. This occurred in the 1790s, towards the end of the first Industrial Revolution, as the ‘Luddites’ fought to preserve their livelihoods; towards the end of the third technological revolution at the turn of the 20th century, with the rise of working class movements, notably in Britain, Germany and Russia; and towards the end of the fourth, when revolutionary fervour swept across across Europe, Latin America and Asia in 1968. These protests were a backlash against the over-promise and under-delivery of modernity for the majority of society, fuelled by a disenchantment, especially amongst the young, with a world that has enough wealth but chooses not to share it fairly. “The stage is [now] set for the decline of the whole mode of growth and for the next technological revolution”17 — which starts with a ‘big bang’ of new technologies that financial capital, breaking from the status quo, invests in heavily.

Conclusion

Perez’s theory outlines how a new technological revolution occurs approximately every half century and eventually transforms ‘every aspect of society’. The first period of this revolution is driven by financial capital, which ‘forcefully’ drives the diffusion of the new technology, while the second period of this revolution — which follows a bursting of the financial bubble and a widespread recession — is shaped by new regulations that help spread the benefits more evenly. Change begets change as people use the new in ways not previously imagined, which helps spread the revolution further and embeds it into economies and society. Yet, as Perez points out “there will always be plenty of developments outside those trajectories, due to the relative autonomy of science and technology. That is why, when the potential of one revolution is spent, there is a pool of radical innovations capable of coming together to form the next.”18

The cycle of revolutions never stops.

1 Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages — Carlota Perez (2002)

2 As Kodak did in the early 2000s, see chapter five — Innovating Out of a Crisis

3 Ibid. p50

4 Ibid. p100

5 Ibid. p105

6 Ibid. p52

7 Ibid. p52

8 Ibid. p120

9 Ibid. p114

10 Ibid. p135 quoting Arthur, W. Brian (2002), ‘Is Technology Over? If History Is a Guide, It IsNot’, Business 2.0, March, pp. 65–72

11 Ibid. p165

12 Ibid. p54

13 Ibid. p145

14 Ibid. p153

15 Ibid. p54

16 Ibid. p55

17 Ibid. p56

18 Ibid. p155