“A peak always conceals a treacherous valley”. — Shigetaka Komori. Former chairman and CEO, Fujifilm1

The business world loves case studies for their ability to convey a complete story — from unexpected disruption to successful resolution — succinctly, with compelling insights and clear take-aways. However, case studies also come in for some justified criticism, as they are often used to push managers to adopt ‘solutions’ just because they worked somewhere else in the past2. The selective focus on successes — omitting instances of failure — can create the false impression that this is ‘one right way’ of doing things. Therefore, case studies should be approached with caution. However, the business world remains captivated by them and one of the most widely cited, by business schools and consultants alike, is the Kodak case: the compelling story of the US giant disrupted by a new technology. Except this story isn’t true.

Kodak was founded in 1880 and dominated the camera film industry for over a century until, as the story goes, it missed the switch from analogue to digital photography and went bankrupt. Yet, this is a narrative as wrong as it is simplistic. Kodak was an innovator and even invented the first digital camera in 19753. They were fully aware of the potential the digital revolution had to transform their market. Their downfall wasn’t down to a lack of innovation or foresight, but was a consequence of their own past success. Kodak were simply (and perhaps understandably) reluctant to forgo the certainty of profits ($1.4 billion in 2001 alone) in their current market for the uncertain gains of a still emerging market. Their mistake was not failing to exploit future potential — it was trying to conserve existing profits at the same time.

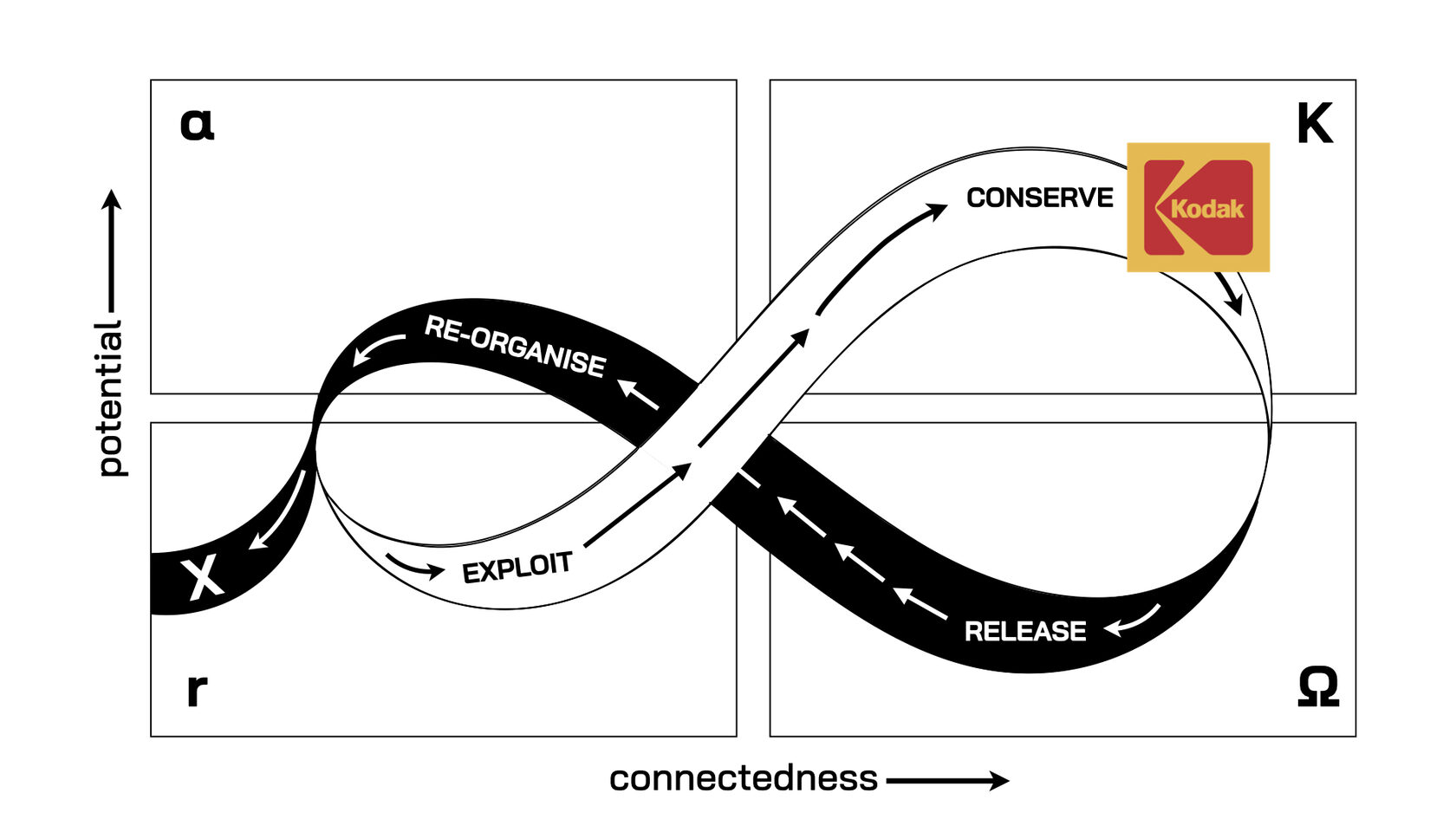

Fig.10: Kodak’s ‘Conservation Trap’

Kodak executives thought they had time to adapt, so tried to conserve (K) their current profits for as long as possible. But, by the time they fully committed to digital (becoming the market leader by digital camera sales in 2005), the world had re-organised (ɑ). The mobile phone revolution saw digital cameras embedded into every device, reducing the demand for stand-alone digital cameras. While new trends, such as ‘selfies’ — which required high quality front and rear-facing cameras — transformed digital cameras into a mass produced, low margin commodity. When Kodak eventually pivoted to this market it was insufficient to sustain the giant. Kodak had fallen into the conservation trap — clinging to past success in a dying ecosystem, which prevented them from reorganising and adapting in time to the new world unfolding around them.

The Case of Fujifilm

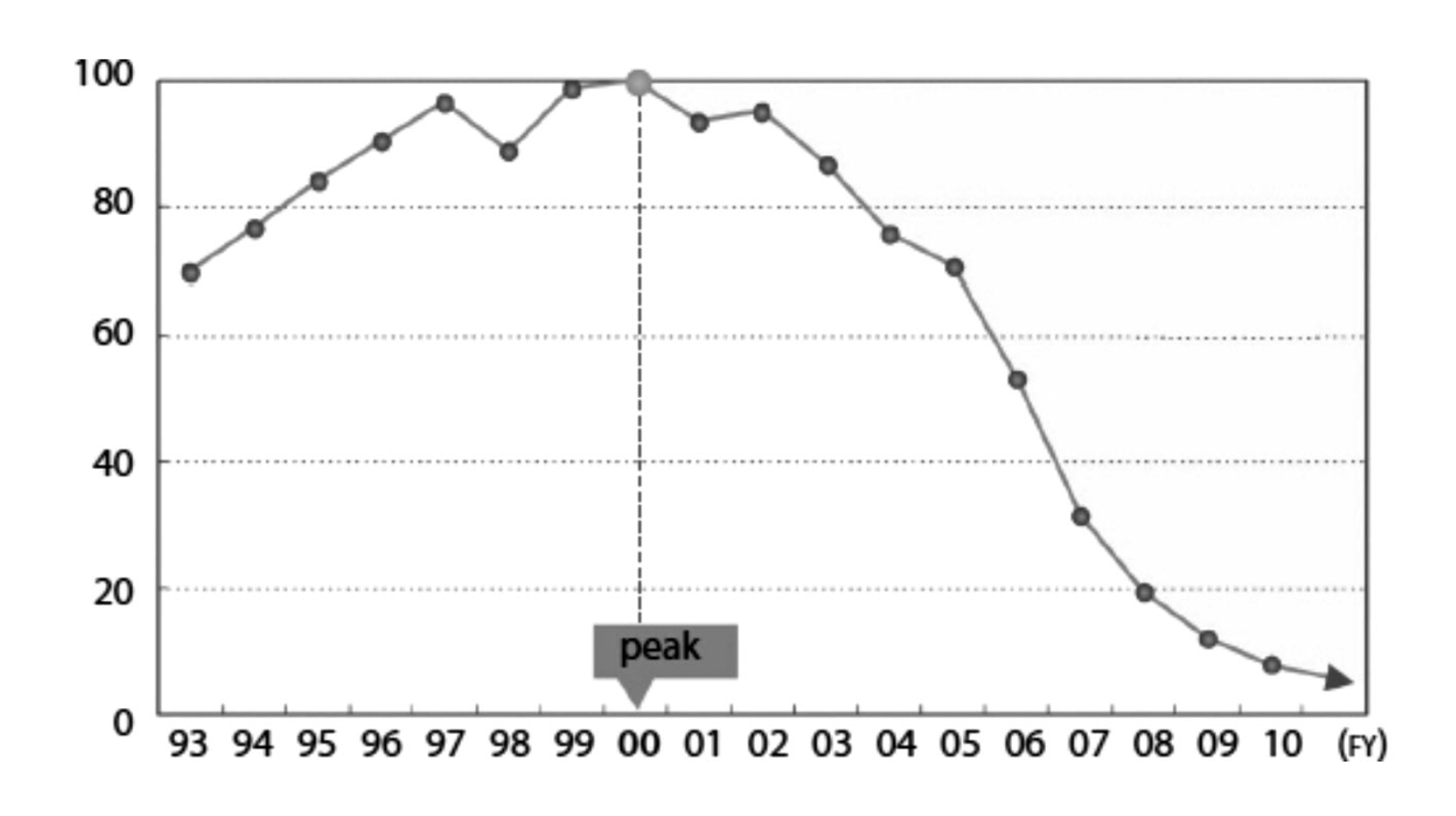

Despite this fascination with case studies, Fujifilm — Kodak’s smaller Japanese rival — receives far less attention from business schools, consultants, and conference speakers in the West4. Yet, like Kodak, Fujifilm had been heavily-dependent on camera film sales, which accounted for two-thirds of their profits at the market’s peak in 2000. Therefore, Fujifilm faced the same precipitous collapse of their market, that came slowly at first, but then rapidly. By 2006, the market for colour photo film was in a death spiral, plunging 20-30% per year. By 2010, it was worth less than a tenth of the value it had a decade earlier. In the words of Fujifilm’s CEO at the time, Shigetaka Komori, the implosion of their core market in the “blink of an eye” was “an earth-shattering event". However, unlike Kodak, Fujifilm not only survived but thrived. This was a ‘live player’ 5— able to do things others had not done before.

Fig.11: Global Demand For Colour Photo Film

Source: ‘Innovating Out of Crisis: How Fujifilm Survived (and Thrived) As Its Core Business Was Vanishing’. Shigetaka Komori (2015).

Fujifilm’s first step was to commit to their mission ‘to protect the culture of photography’. Despite knowing that a huge storm was coming, they didn’t abandon their customers and continued making colour camera film, albeit with the “decisive cuts” necessary to survive a shrinking market. However, these cuts were less about preserving profitability and dividends and more about buying them time to act. And act they did.

Next, Fujifilm started “investing heavily in new businesses [they] thought had a promising future”, focusing on industries where they could leverage their expertise, like pharmaceuticals and highly-functional materials. Cosmetics became a key focus area, which may seem a surprising choice for a photography company until one realises the chief ingredient in film, gelatine, is derived from collagen, which makes up 70% of human skin, giving it its sheen and elasticity. The same oxidation process that ages skin also fades colour photos and Fujifilm had eight decades of research into this process, which they leveraged into anti-aging cosmetics — a booming industry in the large, wealthy market of Japan with one of the world’s longest life expectancies.

Fujifilm invested in other promising areas also, such as “polarising plate protective film … an essential ingredient in the manufacture of liquid crystal panels”. This had been a niche industry providing a crucial component in TV, computer and mobile phone screens but, as the mobile revolution erupted in the 2000s, “what was only ¥2 billion in sales at the beginning of 1990” was transformed into a business worth “¥200 billion twenty years later, easily making up for the losses incurred” in Fujifilm’s core market.

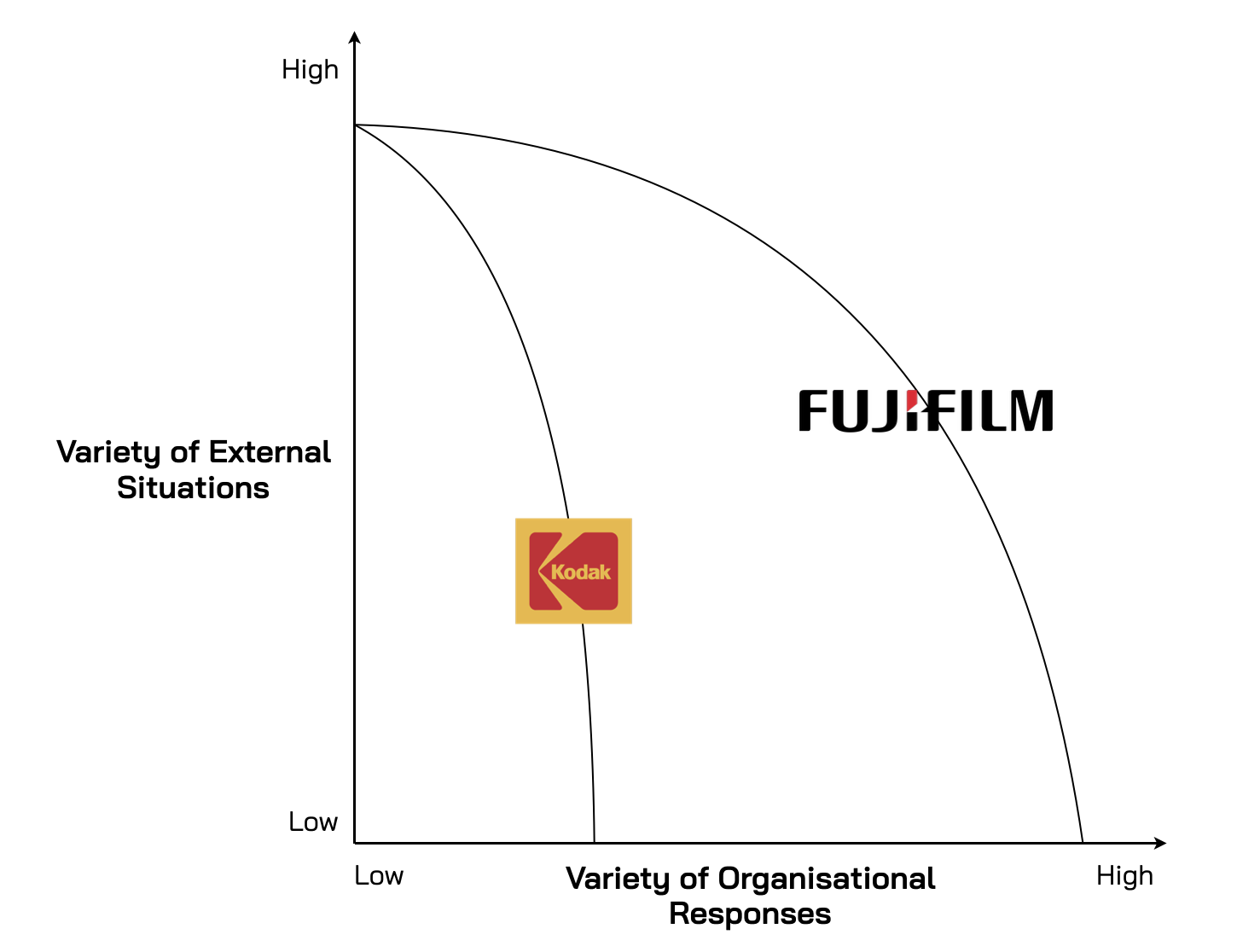

Here we see Pal’chinskii’s first principle in action — Fujifilm increased their chance of success by experimenting with a variety of ideas. They invested $1.8 billion annually in R&D and made“active use” of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) to acquire “companies that [had] already left the starting gate”. By “combining their assets with Fujifilm’s expertise” they got “new products to market quickly and easily”.

We can also see Pal’chinskii’s second principle in action — as Fujifilm also accepted that some failure was inevitable, so kept projects on a small enough scale that failure was survivable. They hedged their bets, spending over $6 billion across 40 companies to quickly “build a presence” in new markets, like software technology, medical devices and inkjet printing. If any venture failed, losses could be off-set by success in other areas — giving Fujifilm the requisite variety of responses needed to survive in uncertain times.

Fig.12: High-AQ (Fujifilm) vs. Low-AQ (Kodak) Companies

Like Pal’chinskii before him, Fujifilm’s CEO, Komori was open to learning from others and actively encouraged his people to seek advice from “outside experts”, especially where they lacked “internal competence”. But he also made one thing clear to his people — “think for yourselves!” Relying on outside consultants to tell you how to run your own company, he warned, was “out of the question”, as “strangers” couldn’t possibly know, or care about, Fujifilm’s situation more than its own people. Instead, Komori urged decision-makers to get closer to the action, learn what was working and focus on whatever showed signs of success. — Pal’chinskii’s third principle in action (develop effective feedback loops between decision-makers and those closest to the action to quickly identify and select what works in their local context).

This was how Fujifilm navigated the storm successfully. In January 2012, as Kodak was filing for bankruptcy, Fujifilm posted record annual net sales of $21.4 billion. Komori credited his company’s sense of urgency as essential to their success. “Had we delayed by just another year or two” he observed, “we would have been right in the middle of the devastating financial downturn in the fall of 2008 and the company might not have been able to survive this double punch”. This ability to act quickly, cultivated by years of having to operate in Kodak’s “colossal shadow”, made Fujifilm resemble the smaller prehistoric mammals6 who survived a planetary shock, whilst Kodak — the “premier company in photographic film for so long” — resembled the previously dominant dinosaurs — too “slow to adapt ” to a world that was changing faster than they could respond to.

1 All quotes in this chapter are taken from ‘Innovating Out of Crisis: How Fujifilm Survived (and Thrived) As Its Core Business Was Vanishing’ by Shigetaka Komori (2015)

2 For an explanation of why copying what worked somewhere else provides no guarantee it’ll work the same way again see, Introduction: Why "Best Practices" Are Holding You Back

3 https://petapixel.com/2018/10/19/why-kodak-died-and-fujifilm-thrived-a-tale-of-two-film-companies/

4 Perhaps because the story is more complex, without a simple takeaway like “disrupt yourself before others disrupt you,” which fuelled countless consultant-led transformations.