The West often seems reluctant to learn from the East. Many Western leaders ignored the strategies deployed by Asia nations in response to COVID-19, despite clear evidence of their effectiveness1. This ‘reluctance to learn’ may be due to the fact that Eastern approaches to strategy are so fundamentally different that they often confuse those trained in Western traditions2. To make these Eastern successes comprehensible, they have to be recast into more familiar Western concepts first — but this translation often results in the critical insights being lost. A prime example of this is another case study that used to be cherished by Western business schools: How Honda beat the British in the US motorcycle industry.

British companies, like BSA, used to dominate the lucrative US motorcycle market. But, in the 1960s their fortunes plummeted as they were outcompeted by a new rival — the Japanese firm, Honda. In response to the unfolding defeat of their national champions, the UK government contracted the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) to provide ‘strategic alternatives’. BCG’s 120 page report analysed how the upstart Japanese firm had outmanoeuvred its more established rivals: Honda had leveraged its position as the ‘low-price leader’ in Japan to “force entry into the US market3” and then expanded aggressively by targeting new market segments. BCG’s narrative was so compelling it became a Harvard Business School (HBS) case study, taught worldwide as a “best practice" for market entry strategy.

However, some years later, the six Japanese executives responsible for Honda’s entry into the US accepted an invitation from an American management consultant to discuss what really happened and a very different narrative emerged. The invitation came from Richard Pascale, who was a rarity at that time, as he believed that US companies should “look at what it was that Japanese companies were doing better than them, and to learn their lessons4”. He published the findings from his interviews with the executives in a paper that became known as ‘Honda B’ (to distinguish it from ‘Honda A’ — the original HBS case study). Honda B was a revelation. Instead of the “streamlined strategy” BCG had lauded, Honda’s executives admitted they didn't really have a strategy at all, at least, not in the western sense of the word. Their success, Pascale surmised, was the result of “miscalculation, serendipity, and organisational learning5”. Furthermore, this was intentional.

Honda B

In post-war Japan, Honda built a reputation for powerful motorbikes and became the market leader in their industry. Yet the uncertain, and occasionally chaotic, environment of the time taught them they should be continually seeking out other, potentially valuable niches to exploit as well. One such niche centred around the emerging need of small Japanese businesses for a lighter, inexpensive motorcycle to make deliveries on. So, in 1958, Honda launched the 50cc Supercub and found themselves “engulfed by demand6”. This success emboldened Honda to try and enter the lucrative US motorcycle market. Following an exploratory visit by two executives the following year, Honda made the decision to proceed. But, “in truth” one of the executives told Pascale, they “had no strategy other than the idea of seeing if we could sell something in the United States7”.

Honda’s market entry into the US went badly. They had faced difficulties obtaining a currency permit from the Japanese Ministry of Finance, leaving them with only a fraction of the funds they thought they needed. To reduce costs whilst in the US, the Honda executives shared an apartment, with two of them sleeping on the floor and rented a run-down warehouse on the outskirts of town. There they stacked the motorcycles themselves to save on labour costs and commuted back and forth on their Supercubs, brought along as a cheap source of transport. Then, their problems really started. Honda’s powerful motorbikes, which they saw as their best chance of cracking the US market, began to suffer mechanical failures. It turned out that Americans drove further and faster than the Japanese and were driving Honda’s flagship product into the ground. The executives had no choice but to suspend sales until their R&D team in Japan found a solution.

At their lowest point, the executives received a phone call from a potential new buyer. A sporting goods chain — not Honda’s typical distributor — enquired about the Supercubs the executives had been seen whizzing around town on. At first, the executives hesitated. Their assumption was that Americans loved powerful motorbikes, so selling the Supercubs might undermine Honda’s brand among ‘serious’ motorbike enthusiasts. But, with their powerful (and now flawed) motorbikes temporarily unsellable, the executives were desperate. They reasoned that, as the sporting goods chain catered to a different market segment, selling the Supercubs wouldn’t impact their core market. So they agreed. And to their surprise and delight, sales of the Supercubs rocketed. Five years later, nearly one out of every two motorbikes sold in the US was a Honda.

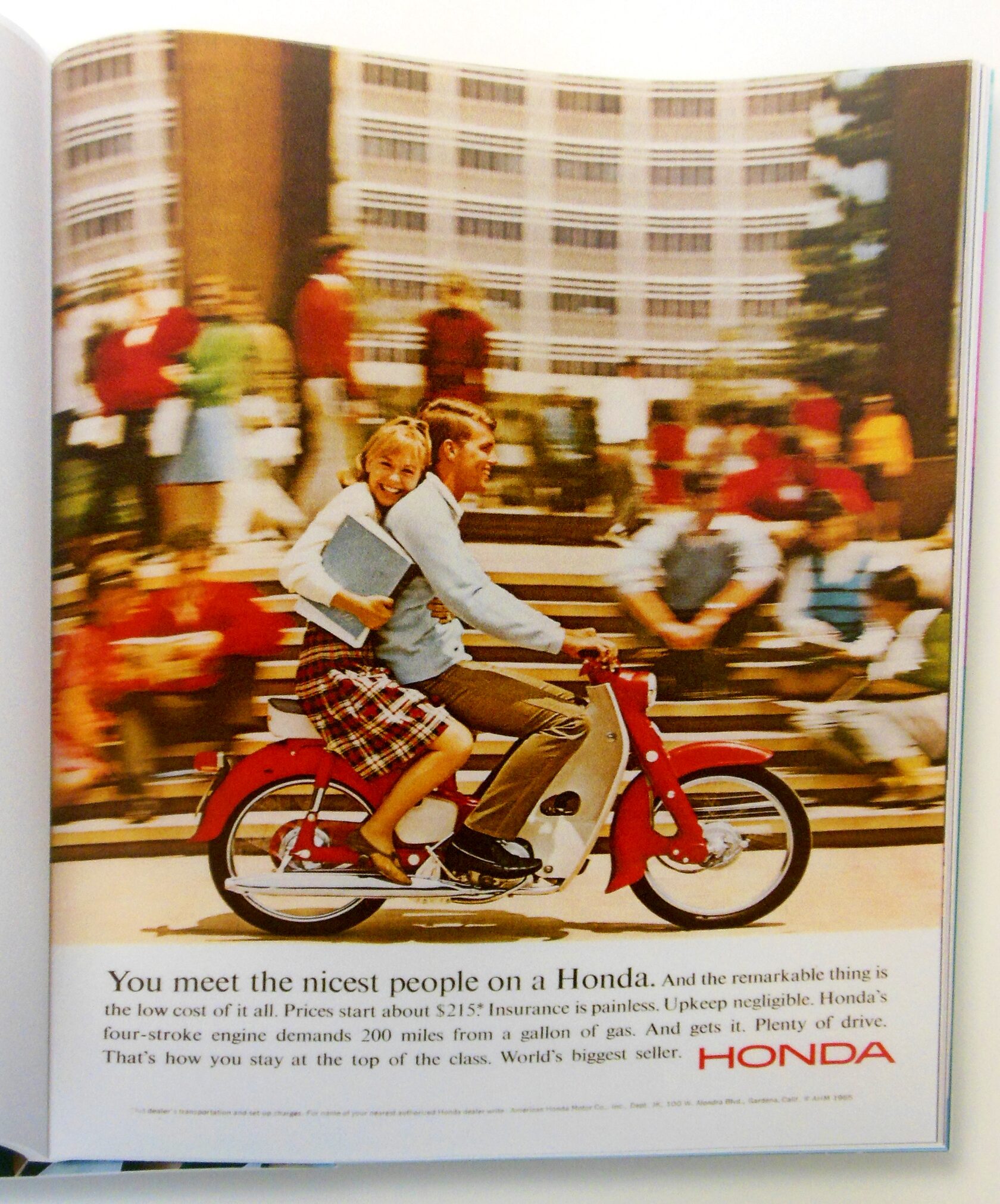

Honda’s success, as the executives later admitted, was not due to the ‘focused strategy’ attributed to them later by BCG. Their aim had simply been to see if they could sell some of Honda’s flagship motorbikes in the world’s biggest market, which had been de-railed by unexpected mechanical failures. They never intended to sell the smaller Supercubs, but simply acted flexibly enough when an offer came through at a time of need. Even their successful, award-winning ad campaign — “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda”, (also praised in the HBS case study) — turned out to have been a happy accident. Their catchy slogan had been created by a student at a local university for a course assignment and sent to Honda’s advertising agency by the teacher. The executives, once again, simply displayed the good sense to go with it.

Fig.13: “You meet the nicest people on a Honda” Advert

The Lessons of Honda B

In response to Pascale’s ‘Honda B’ paper some commentators argued that “Honda has been too successful too often for accident and serendipity to provide a persuasive explanation of its success8”. But, as Pascale explained, there is more to ‘accident and serendipity’ than mere chance. The “Japanese are somewhat distrustful of a single ‘strategy’ … for any idea that focuses attention does so at the expense of peripheral vision9”. Honda’s executives were purposefully not bound by a rigid plan, prepared in advance, far from the frontline. Instead, they had been encouraged to ‘learn as you go’, making the next best moves in front of them — whether selling the Supercubs, or adopting an slogan from a student’s course assignment.

This was one of the key lessons Pascale wanted US firms to learn from the East:

“How an organisation deals with miscalculations, mistakes and serendipitous events [is] crucial to success over time … Rarely does one leader (or a strategic planning group) produce a bold strategy that guides a firm unerringly. Far more frequently, the input is from below. It is this ability of an organisation to move information and ideas from the bottom to the top and back again in continuous dialogue that the Japanese value above all things. As this dialogue is pursued, what in hindsight may be [seen as] “strategy” evolves10”.

Honda B provides valuable insights into the Eastern approach to strategy. A broad direction is set, (e.g. cracking the US market) but the moves needed to deliver success are decided locally by those closest to the action. In unfamiliar markets, those rife with uncertainty, progress comes from continually learning and adapting as you go. Here again, we see the echoes of Pal’chinskii’s Principles:

- Honda expanded into the US to increase their variety of markets and chances of overall success.

- The US team was small and had limited resources, ensuring any failure would be survivable for Honda.

- The US executives responded to changing conditions, selecting what worked (or didn’t) in that context.

To those educated in the strong strategic planning traditions of the West,11 a strategy based on ‘setting a direction and adapting as you go’ can appear insufficiently rigorous. But, the question we have is, should we re-write history to fit Western assumptions (as BCG and the HBS case study did) or should we try to learn how this very different approach to strategy creates value?

In the next chapter, we’ll explore how Honda responded when they were the one being threatened by an upstart company — in what became known as the Honda-Yamaha war.

1 By June 2022 Asia, despite having a population 4 times bigger than the combined West (Europe + US + Canada + Australia + New Zealand) — 4.7 billion vs 1.15 billion — had just half the total cases (159 million vs 300 million) and lost half the amount of people to the disease (1.43 million vs 2.93 million).

In percentage terms only 3% of people in Asia caught CoVid compared to 26% in the West. And only 0.03% of the Asian population died from this, compared to 0.3% of those in the West.

This suggests that, despite the pandemic breaking out in the East first — offering those in the West examples about how to deal with CoVid — these lessons were ignored.

2 This is the central hypothesis of Derek M.C. Yuen in ‘Deciphering Sun Tzu’ (2014). We will make more use of this work in chapter 8.

3 The Honda Effect. R.Pascale. (1996) California Management Review, Vol 38, No. 4 p84

5 The Honda Effect. R.Pascale. (1996) California Management Review, Vol 38, No. 4 p84

6 The Honda Effect. R.Pascale. (1996) California Management Review, Vol 38, No. 4 p85

7 The Honda Effect. R.Pascale. (1996) California Management Review, Vol 38, No. 4 p86

8 Obliquity: Why our goals are best achieved indirectly. John Kay (2011) p95

9 The Honda Effect. R.Pascale. (1996) California Management Review, Vol 38, No. 4 p80

10 The Honda Effect. R.Pascale. (1996) California Management Review, Vol 38, No. 4 pp89-90