During the first world war a company of Italian troops were camped in the Alps. Their commanding officer sent a small group on a scouting mission, but shortly after it began snowing and continued heavily for two days. The scouting squad didn’t return. The officer suffered a paroxysm of guilt believing he had sent his men to their death.

Unexpectedly, three days later the scouting party returned and there was great relief and joy in the camp. The commanding officer questioned his men eagerly about what happened and how they survived. “We got lost in the snow” replied the sergeant who had led the scouts. “We’d given up hope and resigned ourselves to die. Then one of the men found a map in his bag and we used it to navigate our way back”.

The officer asked to see this life-saving map. But when he looked at it closely he saw it was not a map of the Alps at all, but of the Pyrenees1.

***

Maps help us orientate — to see where we are, focus in the right direction, identify viable options for movement and track progress as we go. This is why any map is better than no map at all, as all maps foster deeper discussions and build alignment. Maps work as a common language intelligible to all, allowing people to challenge assumptions constructively and agree on why it’s better to go this way rather than that. Maps enable leaders to tap into their team’s collective intelligence, relieving them of the sole burden of having to find the right way and then convincing others to follow.

Rather than relying on cases or best practices, that simply offer organisations a story about what others did in a similar situation as a potential guide for action, maps help you tap into the collective intelligence of your team. This increases your chances of identifying unorthodox winning moves2, as a team’s combined knowledge is always greater than the knowledge of any individual in it. Involving people in strategic thinking from the start not only enhances alignment but also improves execution, as questions about implementation — how can we make this move — are addressed earlier. The team can now act in unison, moving through their Landscape effortlessly, focused on their common aim. When unexpected obstacles arise they can course-correct quickly using maps. Ultimately, it’s this awareness of the right moves in your context, and the ability to adapt in real-time, that brings victory.

Rather than relying on cases or best practices, that simply offer organisations a story about what others did in a similar situation as a potential guide for action, maps help you tap into the collective intelligence of your team. This increases your chances of identifying unorthodox winning moves2, as a team’s combined knowledge is always greater than the knowledge of any individual in it. Involving people in strategic thinking from the start not only enhances alignment but also improves execution, as questions about implementation — how can we make this move — are addressed earlier. The team can now act in unison, moving through their Landscape effortlessly, focused on their common aim. When unexpected obstacles arise they can course-correct quickly using maps. Ultimately, it’s this awareness of the right moves in your context, and the ability to adapt in real-time, that brings victory.

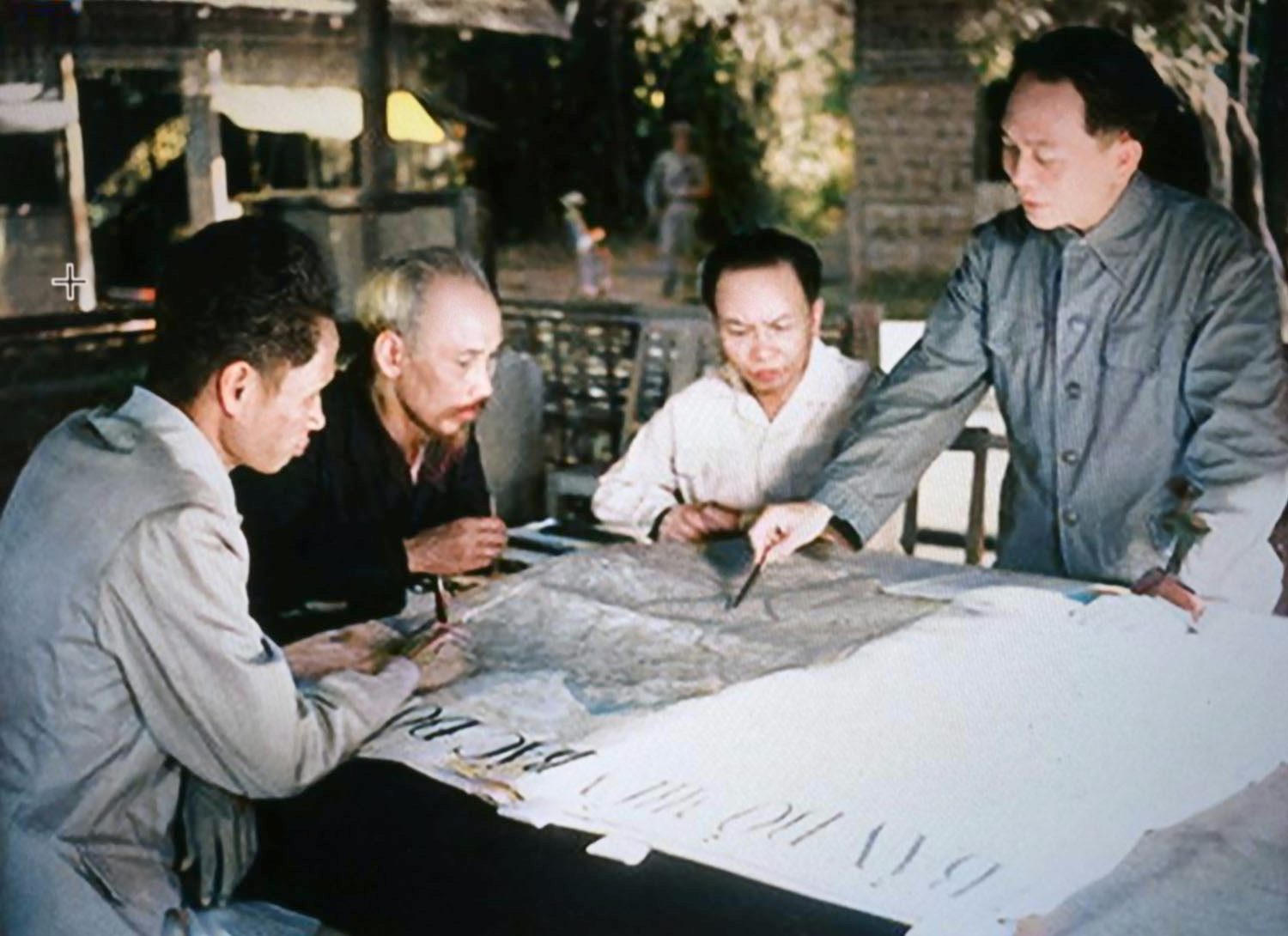

Fig.32: Using Maps to Discussing Strategic Moves

Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap prepare to lead the Viet Minh against the French at Dien Bien Phu on May 7, 1954, the decisive moment that permanently expelled the French Empire from the region.

Fig.33: Using Maps as a Common Language to Create Alignment

Most organisations don’t use maps3, leaving leaders to make decisions blindly, often leaping without looking4. Yet, modern organisations are far too complex for any leader to have their entire business Landscape, and all its moving parts, in their heads. Even exceptional leaders, those who know the details and see the big picture clearly as well, need a clear way to communicate with others who lack this awareness. But this is harder than it seems. For example, try to give someone verbal directions to a place 100kms away — then compare how much easier this is with a map. That’s why we use maps in so many walks of life — they give us the ability to see what’s going on around us and find good options for action. It’s time the business world caught up.

Six Characteristics of Maps

A map is not the Landscape, but a reasonable map helps you to understand the current situation more clearly and identify where your options for action are. This is because maps are:

1. Visual

2. Context-specific

3. Have an anchor

4. Show relevant components

5. Show position

6. Reveal potential for movement.

1. Visual

Maps allow us to quickly scan an entire Landscape, deepening our awareness of the current situation and helping us to identify options for movement, or action. Think of Themistocles using a map to scan the whole of Greece before settling on an ambush at Thermopylae. In contrast, businesses tend to make decisions based on the most convincing narrative, which often means the one in the prettiest PowerPoint slides.

2. Context-specific

No two Landscapes are the same, so no two maps should be either. Themistocles didn’t use a map of France to determine the defence of Greece, even though France has many of the same features (mountains, coastline, central cities). He used a map of Greece. Yet, many businesses copy the strategies of other organisations in different industries or even countries, ignoring key differences in culture, law, or even time. Learning from others is wise — but blindly copying others is cargo cultism.5

3. Have An Anchor

A compass anchors a map, showing direction. King Leonidas didn’t wander aimlessly; he led his Spartans directly north to Thermopylae. For organisations, their North Star are user needs. It’s only by satisfying the needs of users — whether customers, shareholders or employees — that the organisation creates value.

4. Show Relevant Components

Maps highlight critical features like rivers and mountains, buildings and streets. Themistocles could see how to use components in the Greek Landscape, like the narrow pass at Thermopylae, as a force multiplier6. A map of a business Landscape also shows key components, such as products or services that satisfy user needs, and everything else needed to make those, such as resources, technologies, practices, data and knowledge.

5. Show Position

Maps reveal the position of components relative to the anchor. Themistocles focused on Thermopylae because it was on the Persian’s invasion path south. Similarly, a map of a business Landscape shows the position of components relative to users. Front-end components most visible to them — products or services — are the ones they care about most; whilst the back-end components needed to make those — though important to you — are invisible to users, so they care about these less.

6. Reveal Potential For Movement

These characteristics of maps provide the potential for movement — or strategic action. The Greeks understood why this move here (defining the pass at Thermopylae) was better than those moves there. And a real map of your business Landscape will enable you to identify better options for action — enabling you to out-think and out-move your rivals.

So, let’s get started on creating a Wardley Map — the only real maps for business.

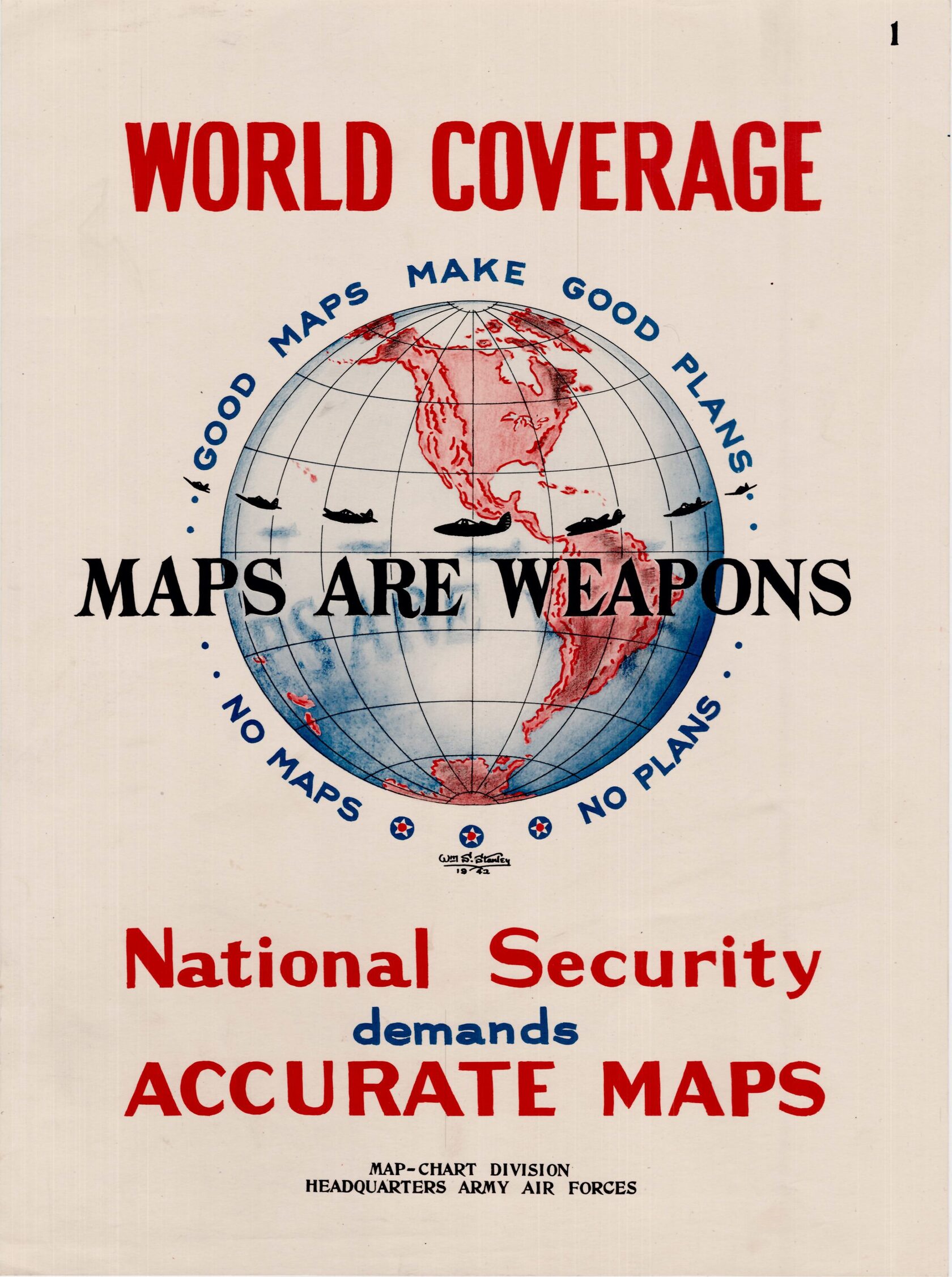

Fig.34: Maps Are Weapons

1 There are several versions of this story which appeared to have first been shared at a medical conference in 1972 by Nobel Laureate, Albert Szent-Gyorgyi who, whilst a medical student in Budapest, served in World War 1. https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2012/04/23/any-old-map-will-do-meets-god-is-in-every-leaf-of-every-tree/

2 See difference #1 in chapter ten — Strategy for an Uncertain World for the discussion on why winning moves are unorthodox moves.

3 Most organisations of course have many things they call maps (mind maps, road maps, process maps etc) but, as we’ll show in chapter eighteen — On False Maps — those are not real maps.